Hunger no more

Polk County Supervisors are raising $10 million to help end hunger in Polk County.

MEGAN VERHELST Oct 2, 2015 | 11:00 am

10 min read time

2,460 wordsArts and Culture, Business Record InsiderA snapshot of the problem:

Feeding America estimates that more than 55,000 people in Polk County identify as food insecure. Sarai Rice, executive director of the Des Moines Area Religious Council, believes that number is much higher — closer to 70,000 or 80,000 people. One in five children go hungry every day, as do one in eight adults.

A proposed solution:

The Partnership for a Hunger-Free Polk County is a collaboration between the Polk County Board of Supervisors and the Polk County Health Department as well as human service nonprofits, including: Des Moines Area Religious Council (DMARC), which operates food pantries throughout the metropolitan area; Urban Dreams; Meals on Wheels; Eat Greater Des Moines; local food banks, and others. The partnership’s goal is to improve communication between all entities, increase awareness and access to services to food-insecure residents, secure more money to explore systematic ways to collect more food, and, in the end, work together to reduce hunger in Polk County.

In the coming days, the Polk County Board of Supervisors and more than 100 partners will issue a challenge to Greater Des Moines to eliminate a problem that affects more than 50,000 county residents.

In tandem with the Iowa Hunger Summit on Oct. 13, they will announce the official launch of the Partnership for a Hunger-Free Polk County. Led by Supervisors John Mauro and Angela Connolly, the partnership seeks to raise $10 million to reduce or eliminate food insecurity among Polk County residents.

Despite an improving economy — and despite the accolades Des Moines receives on a regular basis — food insecurity is a problem in our community, Mauro said.

“This is a Polk County issue. Everyone thinks it’s an inner-city issue, but it’s not. It’s everywhere. There are pantries everywhere — in all the suburbs, but people don’t see that,” Mauro said. “And it’s time for everyone to say, ‘Enough is enough.’ ”

THE ISSUE

How did we get here?

In June, the DMARC Food Pantry Network served an all-time record high of 5,652 families, comprising 14,785 individuals. They represent usage increases of 27 percent and 21 percent, respectively, from a year earlier. In addition, DMARC served 424 families who said they had never used a food pantry before.

Why the double-digit increase? Pantry usage started to stabilize in March of this year, about the time DMARC, in partnership with the county, opened the River Place Food Pantry at 2309 Euclid Ave. The pantry opened March 9 in northeast Des Moines, which previously had no pantry. It has since become the most-used pantry in DMARC’s network. Approximately 1,600 families use it each month, 70 percent of whom reported being first-time users.

“In addition to the unbelievable volume of people using the River Place pantry, a high percentage of those users are older adults — 20 to 25 percent compared to the 7 percent we normally serve,” Rice said. “We think it’s because people know how to get there. Other services are offered there, it’s open from 8 to 5, and the bus stops right there. We’ve finally given access to a whole group of people who needed it and now have a way to find it.”

DMARC also moved into a larger headquarters at 1435 Mulberry St., which by increasing its storage space, allowed the organization to buy more food in bulk at reduced prices.

Still, it’s not enough, Rice said.

“We saved more than $240,000 by paying less for food because we can store it here,” she said. “But we’ve also had more people eating that food. It’s really a question of volume. We know how to do the work, but we need to provide more food, which means we need more funding.”

Addressing such issues from a systematic perspective would increase the effectiveness of DMARC and other organizations.

“We need to look at the system as a whole and make it operate better,” Rice said. “Everybody plays a role. … Hunger is huge, and the effects of hunger are huge. What we have is a world full of children who don’t get the nutrition they need, and they will never make that up. You can’t eat all the carrots in the world now and expect to make up for (childhood malnutrition).

“You should not have to aspire to carrots. Carrots should be a fundamental right.”

THE SOLUTION

About a year ago, John Mauro read a letter to the editor in The Des Moines Register written by Jim Marcovis, owner of G & L Clothing. The letter addressed hunger in Polk County, stating that one out of every five kids in Polk County do not have enough to eat.

“It struck me,” Mauro said. “We know we have an issue here, but no one wants to face it. It’s at the point of a crisis. When you talk about 50,000 out of 450,000? That’s not right. Things have been good for us here in Polk County, but why are we just letting this go?”

For Mauro, it was time to step up and make a difference.

Angela Connolly agrees.

“Our community churches want to help. DMARC has 13 food pantries, but it’s not enough,” Connolly said. “We’re not just talking about people living under bridges here. Some families affected by this work two or three jobs, but they have kids and they are feeding their kids before they feed themselves. These are working families that need food.”

Both Mauro and Connolly said that if those working to solve the problem were better coordinated, hunger could be reduced.

That is one of the primary goals of the Partnership for a Hunger-Free Polk County. The first steps toward its creation came nearly a year ago. Mauro contacted Marcovis, and the pair created a small group consisting of representatives from the Polk County Health Department, United Way of Central Iowa, Broadlawns Medical Center and other groups.

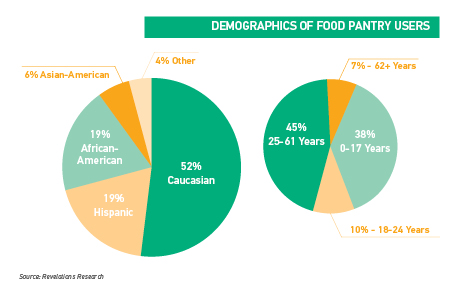

The group spent six months researching what organizations throughout Polk County were doing to address food insecurity, where the system was falling short, and what solutions were possible. The group brought in Revelations Research to conduct a study. The company held focus groups with 33 different service providers and surveyed 409 food recipients.

In the end, Mauro said he knew the solution had to be a collective effort.

“It can’t just be a few people,” he said. “It can’t just be the wealthy stepping up to solve the problem. It has to be the entire community, and once they know what’s happening, I think they will step up.”

DMARC worked closely with Mauro, Connolly and others in the beginning stages of the partnership’s development, providing data to show them where services existed, where those utilizing the pantry system lived, and how they move around.

“It’s entirely possible there is a better way to do this and we just haven’t thought of it yet,” Rice said. “This community is full of smart people, and bringing more people in with an outside perspective is a good way to solve problems.”

The partnership’s goals are numerous. One is to create more awareness of what is available to Polk County residents who are food insecure. Second is addressing the challenges they face, including transportation, pantry locations and hours of access. Another challenge is to identify and address pockets of need in Des Moines where current resources do not exist, said Jana Rieker, communications manager at Trilix, the company handling communications for the new partnership. Rieker has worked on similar initiatives in the past, including the Polk County Housing Trust Fund.

“What people are lacking is access,” she said. “There is a huge pocket of need right now just east of Valley West Mall in West Des Moines, where residents lack access to both food and public transportation. There was a pocket like that at River Place, but we addressed it.”

In the coming weeks, the partnership will launch a website and a smartphone app containing information that will inform residents of where they can go to get food, locations of pantries, hours of operation and other resources. It also will let residents know where they can volunteer and donate food.

The county also plans to increase awareness among the general public through a new communications campaign.

Another goal of the partnership is to increase collaboration among agencies in Greater Des Moines that all work separately to address the hunger issue. Mauro called the disconnect between agencies “eye-opening.”

“They are all doing great things, but if this were a joint effort, it would not be as difficult to solve,” he said. “What we’re saying is we want to help them achieve a bigger vision and strategy. We want to find them the money to stay open later, to provide more of what they need, to provide choice — and in all honesty, it blows their minds because this hasn’t been done before.”

While those at the helm of the partnership are still ironing out the structure of the group, 14 organizations have signed a covenant to be a part of the partnership. Approximately 30 organizations will attend partnership meetings, and close to 50 groups have expressed interest in participating and receiving communications from the partnership.

Mauro, Connolly and others will continue to lead the group, participate in conversations and hear what needs to be done to help the organizations better accomplish goals.

The overarching goal of the county is not to disrupt what organizations are currently doing, only to enhance those efforts. Tangible goals will be set, one by one, as funding is secured, Mauro said. One goal already outlined is the purchase of a warehouse from the city of Des Moines.

“The city said they will give us a warehouse for $1 per year for three years,” Mauro said. “Our plan is to fix it up and use it as a place to store food. DMARC has the capacity to buy food at wholesale, but they are limited due to storage. This will help them get more food for less money.”

Another goal is to offer additional resources at food pantries, such as materials designed to help individuals find work or better prepare for a job interview. Connolly said the goal is similar to what was done through Project Iowa to address homelessness.

Finally, the partnership plans to explore how to place services closer to areas with the most need. It also will explore placing more pantry sites on bus lines, the addition of mobile pantries and the addition of pantries and evening meal sites in schools.

Rice said the partnership will help accomplish one of DMARC’s biggest goals: locating those in need.

“We know there are more people out there,” she said. “This will help all of us because it means more money in the system to actually feed people, more funding to inform and educate the community and more to find the people who need assistance and aren’t finding it.”

To accomplish these goals, the county needs to raise $10 million over the next five years. In early September, Mauro said he had spoken with five people who, together, committed $250,000 to the partnership. His goal is to have $5 million committed by the partnership’s public launch on Oct. 13.

“Once we raise the money, this will all come to fruition,” Connolly said. “If the partnership thinks a mobile food truck needs to go out into a specific neighborhood, we will ask, ‘Should that be our next goal?’ One pantry wants to stay open longer. Is that our next goal? We will have an advisory committee that will make those decisions, but we won’t make those decisions until the money is in hand.”

Donated funds likely will be managed by the Community Foundation of Greater Des Moines. Final details on the partnership’s structure will determined by the group’s public launch.

Mauro said he is confident the partnership will be able to significantly reduce and eventually eliminate hunger in Polk County.

“We will accomplish this goal. We are going to do this,” Mauro said. “I am convinced we are going to do this.”

Why is hunger growing now?

The Des Moines Area Religious Council’s food pantries saw a spike in clients in November of 2013, said Director Sarai Rice. Ironically, that was the month officials believed the economy had improved enough to reduce the government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits back to pre-recession levels.

It seems counterintuitive, but when the economy improves, Rice said, people tend to receive a few more hours at work or a small bump in pay, which makes many ineligible for the SNAP benefits they once received.

“When you fall off the SNAP roll, it’s like a cliff,” Rice said. “You fall off that cliff, and you are essentially making much less than you were before. You have less money flowing through. So, when unemployment goes down and SNAP usage goes down, food pantry usage goes up. People just don’t understand the mechanics of how this phenomenon works. There is a sense that if the economy is doing better for them, it must be doing better for everyone. That’s just not true.”

A STATIC MINIMUM WAGE

Another factor that contributes to food-insecurity is the state minimum wage, Rice said.

“We are now in the minority of states that have not raised the minimum wage,” she said. “What it is now is in no way sustainable. For a family in Iowa to be sustainable, research shows you need to be at 250 percent of (the federal) poverty level ($60,625 annually for a family of four). That’s with no savings, no mortgage — just enough to cover the basics. We have more than 250,000 people in Polk County who are not there.”

Finally, the problem is invisible to many in Polk County, Rice said, and many involved with the anti-hunger partnership will agree. Although the majority of food-insecure families aren’t in wealthy suburbs like Ankeny or West Des Moines, poverty has a way of following wealth.

“Poverty is closer than you think, no matter where you live,” Rice said. “You may not realize your neighbor is low-income, but if you went to a food pantry, you likely would see a neighbor there.”

STRETCHED RESOURCES

While it’s good that more people have access to pantries, growing pantry usage has a negative consequence.

With more people to serve, DMARC had to reduce the amount of food it allows each family to take. Families used to be given the equivalent of four days of food a month. Now that is just three days of food per month. Serving more people has made it difficult for DMARC to open another pantry on the far south side of Des Moines, or to start a mobile pantry system.