The ADA generation

Employers need workforce, but professionals with disabilities remain largely untapped even after 30 years of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Advocates want to change that.

Emily Barske Wood Feb 13, 2020 | 10:24 pm

17 min read time

4,138 wordsDiversity, Equity and InclusionEditor’s note: Research suggests that if U.S. companies embrace disability inclusion, they will gain access to a new talent pool of more than 10.7 million people. This segment of the unemployment rate has remained relatively unchanged even with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, passed 30 years ago this July. This story is the first in a series about advancing the employment of people with disabilities.

When Alex Watters got a call about a job offer to be a field organizer for President Barack Obama’s reelection campaign, he hesitated. Not because he didn’t have the passion or experience for such a position, but because one of the core functions of a field organizer – knocking doors – was not something he could do.

Watters, who uses a wheelchair, jokes that he wasn’t going to throw rocks at doors that weren’t accessible as an alternative to knocking. But Zack Davis wasn’t looking for someone who could knock as many doors as possible. He was looking for a leader who could rally others to knock on doors, make phone calls and contribute to the grassroots campaign. So Watters accepted the position.

Months later, on a call with all the other field organizers across the state, State Director Brad Anderson asked the others on the call how it felt that the one field organizer who couldn’t himself knock on doors had a team that had knocked on more doors than anyone else in the state. Had the job simply been promoted as needing an organizer who could knock a certain number of doors, he wouldn’t have even thought of applying. This is why Watters, now an elected official himself on the City Council in Sioux City, has made it a point to advocate for accessible practices in hiring and gainfully employing people with disabilities.

It’s not always how he imagined his life would be.

Alex Watters, career development specialist at Morningside College and a member of the City Council in Sioux City, speaks with students. Submitted photo

Watters had a diving accident at Okoboji, where his family is from, that left him paralyzed from the chest down. Before the accident, he was attending Morningside College on a golf scholarship. In months of recovery and rehabilitation from the accident, so many loved ones and health care providers showed him support.

“That really kind of instilled in me this drive, this passion. And this idea that … I need to do something more. And make sure that this doesn’t define me and that I go on to make a difference,” he said. “Because I kept thinking to myself that all of these therapists, these nurses, these doctors, these caregivers, everyone gives so much to these individuals, these people such as myself. It would be a disservice for me to not feel like I want to give back and try to impact people’s lives.”

The transition from the hospital back to his family in Okoboji was difficult. Getting into and out of bed or simply going to watch TV at a friend’s house now had significant barriers.

“It’s scary when you’re going out from a protected environment into an environment that is really not accessible,” Watters said. “Everything in the hospital is very accessible and built to fill those needs. And the real world is not.”

But he learned a new way of life. And he is making the most of it – graduating from college, serving in several government advisory roles, getting offered a position in the White House and ultimately finding his calling as a career development specialist at Morningside College while also serving on the City Council. While his work as an advocate proves there is much more to be done, he said the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 – authored by Iowa’s Sen. Tom Harkin – laid the foundation for some 61 million Americans who have a disability.

Harkin says people like Watters are part of the “ADA generation.” They grew up since the law was passed, are more willing to self-identify their disabilities and take more pride in themselves, he said. “They’re a lot more unwilling to take what society offers. They’re demanding their rights. They’re going to court – and they’re winning. And they’re getting good jobs. And they’re empowering other people.”

This July will mark 30 years since the landmark civil rights legislation was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush. The ADA was intended to give people with disabilities equal opportunity, full participation, independent living and economic self-sufficiency. In many ways, Harkin said, the country has come a long way toward reaching those goals. But the fourth goal of economic self-sufficiency, which is largely reliant on private sector employment, has barely budged, he said.

“That’s the one where we haven’t moved the needle a bit. The unemployment rate for adults with disabilities today, well, it’s a little bit better, but basically, it’s about the same as it was 30 years ago,” Harkin said.

Leveling the playing field

The ADA requires employers to provide reasonable accommodations to its employees with disabilities. But those employers first have to hire them.

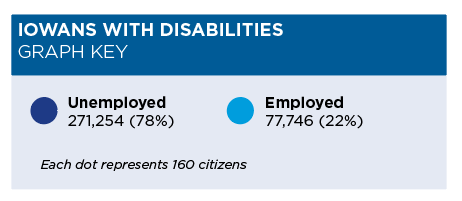

According to data from the Office of Persons with Disabilities, just over 349,000 Iowans in 2017 reported having a disability — representing 11.3% of the state’s civilian, noninstitutionalized population. The number of Iowans between the ages of 18 and 64 with a disability who were employed in 2017 was 77,746, according to the agency.

A report from Accenture also found that 45 companies that researchers identified for leadership in areas specific to disability employment and inclusion had, on average over a four-year period, 28% higher revenue, double the net income and 30% higher economic profit margins than their peers. The analysis also revealed that U.S. gross domestic product could get a boost of up to $25 billion if more people with disabilities joined the labor force.

As of July 2018, only 29% of working-age Americans with disabilities participated in the workforce, compared with 75% of Americans without a disability, according to Accenture. In 2017, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities was more than twice that for those without a disability — 9.2% versus 4.2%. There are 15.1 million people of working age living with disabilities in the U.S., so the research suggests that if companies embrace disability inclusion, they will gain access to a new talent pool of more than 10.7 million people.

Emmanuel Smith and Anne Matte work at Disability Rights Iowa. Photo by Duane Tinkey

Many advocates are working on this issue. Emmanuel Smith is an advocate at Disability Rights Iowa, located in the East Village. He uses a wheelchair because he was born with osteogenesis imperfecta, or brittle bone disease, which affects how his body makes collagen, a protein that helps strengthen bones. Smith said the biggest barrier to employment for people with disabilities is the trepidation and fear employers have. One of the biggest myths, he said, is that accommodations cost a lot of money.

In Smith’s first job at the movie theater at Jordan Creek, his accomodation was minuscule: He needed the place where he was to put tickets moved down a few inches so he could better reach it. “Really hard,” he said with a laugh and a note of sarcasm. This type of accommodation is the norm – statistics show most accommodations are free and those with a cost are usually less than $500. That cost can often be completely covered through government and nonprofit organizations.

Smith is also part of the ADA generation.

“It’s what allowed me to take the bus, to go and get a college degree. It’s what allowed me to feel like I had an opportunity to look for employment and not be prejudged based solely on the disability. And it’s offering me the kinds of protections that are going to help me to live and work in this community throughout my entire life. So there’s really no area in my life that I can’t link directly to the Americans with Disabilities Act,” he said.

Smith stresses that ADA did not create a privileged group; it simply leveled the playing field. Or at least got it closer to level.

Vocational Rehabilitation celebrates 100 years

Smith and others have worked with Iowa Vocational Rehabilitation Services, an employment program for individuals with a disability within the state’s Department of Education but largely funded through federal dollars. Its programs focus on two clients: individuals with disabilities and partnering businesses. Vocational rehabilitation existed long before the ADA and was originally started 100 years ago this year to help World War I veterans get back into the workforce.

Iowa has two voc rehab services – IVRS and the Iowa Department of the Blind.

But since the passage of the ADA, there’s been a heightened awareness about employment of people with disabilities.

“The biggest change is there was legislative legal support to increase the awareness that individuals with disabilities, like all of us, have rights and responsibilities,” IVRS Administrator David Mitchell said. “I think the accessibility piece of all of that is such a critical piece.”

Awareness, advocates say, cannot be underestimated. “I’ve often said that one of the biggest accomplishments [of ADA] was helping to break down the biggest barrier of all, and that’s the attitudinal barrier against persons with disabilities,” Harkin said.

A goal of Harkin and other advocates is not just getting people with disabilities jobs, but getting them competitive, integrated employment. This means jobs that pay above minimum wage (although it’s still legal in some circumstances to pay people with disabilities below that). It means jobs that include them and challenge them just like other employees, not just shoving them in a corner doing menial work.

IVRS works with both businesses looking to hire more people with disabilities and those who are seeking a job. Mitchell said the focus is on aligning businesses with the best person possible and focusing on their ability not their disability.

“As we work with businesses, the focus is really listening to the business – what are your needs? How do we understand what type of person is successful for your business? How do we create opportunities to bridge those gaps and link those services together?” Mitchell said.

Michelle Krefft, IVRS director of business services, has plenty of examples of these partnerships leading to success. Many businesses, she said, have a fear of the unknown, but she recommends listening to the value of hiring people with disabilities from other businesses. Krefft gave a few examples:

Kwik Trip (known in Iowa as Kwik Star) has a retail helper program to assist with guest services. The job was specifically customized for people with severe barriers to employment. The employees get to pick their own hours and have the flexibility needed to accommodate their disability. Many of these employees have been promoted, opening a job for another person with a disability.

Wells Fargo near Jordan Creek contracts out its cleaning and modifies the job to create opportunities for people with severe barriers. The program, which started in Texas, coordinates its hours around the bus schedule as another means to make it accessible.

The work with businesses does not stop once the hire is made. IVRS makes sure the relationship is working out on both ends as the employee begins working. It sometimes helps pay for accommodations or help with training. In some cases, IVRS pays the wages of the employee while they’re receiving training so the business doesn’t face a cost barrier with a specialized program.

As with other state programs, Mitchell said there is always a fear of budget cuts. However, he said his pitch is this: For every state dollar IVRS gets, it gets $4 from the federal government.

Make change from the roots by shifting the mindset

Beatrice Steele was in the process of moving from Atlanta for a new job. As she walked across the street, five months pregnant, she was struck by a drunken driver, causing her to go into a coma and forcing her into early labor.

Her son was born healthy, although he now goes to therapy because of the traumatic birth. But even with months of rehabilitation after the accident, Steele’s life wasn’t the same. She had fractured her skull, had to have her face reconstructed, had a tear in her rotator cuff, had swelling in her feet and had become blind in her right eye. Doctors told her she should just accept the benefits and not look for employment because she’d never be able to have a job again.

“I started to believe what people were telling me,” she said.

With no job, she fell into depression, feeling at a loss that she couldn’t provide for her kids as an unemployed single mom. Through therapy, she recovered more and more both physically and mentally. “I have things that will always be wrong with me, but I know how to cope with it.”

And she decided not to listen to the negative advice she was given.

She was connected with IVRS. She got a job at Prudential in Dubuque and has been promoted three times. The opportunity has lessened her depression. “They gave me a chance. I have these disabilities, but there’s something I can do. And I’m doing it well.”

Most rewarding was a day in 2018, when her son whom she was pregnant with during the accident, got to come to see her at work for a first grade class trip. From never thinking she’d get to work again to having her kids see her working was very exciting, she said.

Stories like Steele’s of deeming a person with a disability unemployable because of attitudinal barriers are not uncommon. Disability advocates recognize this is a holistic problem: People with disabilities and businesses have to be equally open to employment. And everything from hiring practices to full inclusion has to be understood.

Krefft said it’s important that job descriptions aren’t unnecessarily limiting. For example, some descriptions might say the applicant needs a driver’s license, which excludes some people with disabilities, when it really means the applicant must be able to get to work. Or a job description might say the applicant needs to be able to lift a certain weight, when that’s not a true function of the job.

While Prudential’s flexibility is exemplary, advocates know it isn’t always the case. Even when businesses do hire people with disabilities, they too often create another problem, Harkin said.

“The training program is designed only for persons without any physical or intellectual or developmental disabilities,” he said. “The person with the disability, physical disability or otherwise, probably can’t make it through the training program.

“So why don’t you change the training program to accommodate persons with disabilities? It might take you a little bit longer to get through the training program, you might have to do some things a little bit different in the training program. But at the end of it, you will have a person qualified for the job that will be one of your best employees.

“It’s not enough to just reach out to folks with disabilities to let them know the job is open. They want to know that accommodations will be made, that they will be treated just like any other employee, they will not be shunned aside or put in some special place. They will have the full benefits and everything else of every other employee.”

The benefits

Advocates promote the idea that hiring people with disabilities is not just an inclusive decision – it’s good business practice.

“The real reason to hire a person with a disability is because you’re missing out on opportunities if you don’t,” Smith said. “It’s not charity, it’s an act of empowering your business to succeed in new ways.”

With workforce being the top priority for nearly every business in Iowa, Mitchell said this is the perfect time to look at getting more folks with disabilities into the workforce.

Additionally, the government saves money on welfare benefits. Iowa Vocational Rehabilitation Services data shows that after 10 years the state receives an average of $227 return on every $100 of state appropriation originally invested in voc rehab. IVRS found 95% of voc rehab candidates were receiving public support for living expenses, but with a job and economic self-sufficiency they save the state nearly $800,000 annually. Fewer than 4% of those candidates end up moving out of Iowa, data shows, pointing to the high retention and engagement rate.

“One of the biggest pushbacks on ADA is employers think I can do anything I want and fail to meet certain standards without consequence. And unfortunately, that’s not the case. That’d be awesome. It would be nice, you know, to just lounge around here all day,” Smith said, laughing.

In addition, hiring people with disabilities also has an impact on customers’ perspectives of a business.

“Consumers appreciate companies that hire inclusively,” said Kyle Horn, founder of America’s Job Honor Awards, which recognize workforce opportunities for people overcoming employment barriers. “Great things have happened. But we still have a long way to go.”

He emphasizes that businesses are not alone. When looking into hiring people with disabilities, there are many local, state and federal organizations that can help provide resources in addition to funding. Various organizations offer inclusivity training.

Smith said employers should keep in mind that all people with disabilities are individuals and shouldn’t be lumped into a broad group. Sometimes employing a person with a disability, just like employing anyone, doesn’t work out. But, Smith said, you wouldn’t stop hiring all teenagers just because one didn’t work out, so why would you do that for people with disabilities?

“We’re not radioactive, right?” Smith said, laughing. “The best way to learn about employing people with disabilities is to hire some people with disabilities.”

If advocates have it their way, the needle will have significantly moved on the employment of people with disabilities at the next anniversary celebration of ADA.

“I hope we continue to break these barriers down so that people see people with disabilities as contributing members of society and they can fully reach their potential as well, which would not have been possible if it wasn’t for the groundwork, and the foundation that was built by so many with the ADA,” Watters said.

New Harkin Institute building will be ‘state of the art accessible’

Accessible entrances and accessible parking are just two of the elements in building designs required for compliance since the passage of the ADA in 1990. But these features have often stopped there – at compliance. A Des Moines building set to open this fall will include accessible features – beyond compliance – that are designed to eliminate many barriers that people with all kinds of disabilities face.

And what better organization to call the building home than the Harkin Institute on Drake University’s campus. The organization produces nonpartisan research, learning and outreach to promote understanding of the policy issues to which Sen. Tom Harkin devoted his career, including the advancement of people with disabilities.

Harkin said the goal is to make the building the most accessible in the country. Harkin Institute Executive Director Joseph Jones said: “It gives us the opportunity to really work in an environment that matches the quality of work we do.” A hallmark of the new building will be its various gathering spaces to offer programs and other learning opportunities.

“I want to make sure it’s state-of-the-art accessible. And not only accessible physically, but accessible intellectually and socially,” Harkin said.

Kevin Nordmeyer (left), principal at BNIM, and Jason Kruse (right), associate at BNIM examine their design for the new Harkin Institute Building. Photo by Duane Tinkey

The lead architects are making sure of that. Kevin Nordmeyer, principal at BNIM, and Jason Kruse, associate at BNIM, designed the features of the building after conversations with the institute’s accessibility committee. Nordmeyer asked them what building design barriers they still thought existed even with ADA compliance.

Their answer? No one had ever asked them.

Through the conversations and research, Nordmeyer and Kruse designed several features of universal inclusive design. The elements are called universal because they are not only helpful to people with disabilities, but to all people. The committee said the design should be gracious in its space and layout. One key element: They wanted to see a design to get up to the second floor without needing an elevator or stairs.

One of the biggest challenges Nordmeyer and Kruse faced was designing a large-scale ramp that loops around to get to the second level. The ramp inevitably takes more space than stairs, but it creates a way for all people to get up to the second level instead of creating separate means and it’s designed to be the signature visual element in the space. The Ed Roberts Campus at the University of California-Berkeley is one of the few other buildings to incorporate a universally designed ramp like this.

Nordmeyer, who has multiple sclerosis, has a unique perspective on building design. “Thirty-five years or so of my life, I didn’t have to worry about any of this stuff, right? Yes, to follow the rules of the ADA and design space, but now I have a whole different perspective.

“It’s been a 20-year, slow progressive disease to where now they say it’s stable and it’s not necessarily getting any worse. But for me, I gradually I had to use a cane. … As you have to use a wheelchair, you start to realize the limiting factor that it provides if you have a building that’s not really designed the way we’re trying to design this one.”

Jones said the plan has always been to move the Harkin Institute from its current space at 2429 University Ave. It just coincidentally worked out that it would be during the 30th anniversary year of ADA. “It’s hard to believe that 30 years have passed. … It’s made an impact on the world. Now we’re focused on where we go in the next 30 years,” he said.

While the current building provides office space, there isn’t a way to host large groups and the design features are not as accessible as the new space, at 2800 University Ave. Jones is excited for the auditorium, where seats can be taken out to create more room for accessible seating and two screens will be available for live transcription services helpful to those who are hard of hearing.

Some of the other features involve different kinds of lighting and window design meant to affect shadows to accommodate those with low vision. Conference tables are round, not square, so people who are hard of hearing can read the lips of whoever is speaking. Carpets have simple design so that they don’t create a sensory overload. Accessible parking has been designed in a user-friendly way. Restrooms are all single-user direct-access, allowing more space for wheelchairs or other mobility devices. There are benches built in for people who might not be able to walk the entire length of a hallway without needing rest.

“The idea behind the building is that it allows all people, whether you’re in a wheelchair or you’re on the autism spectrum, to be able to be empowered as an individual and potentially use this as a workspace. So looking at the building to create this environment that is inclusive and allows people of all abilities to be able to thrive is one of the main goals of the project,” Kruse said.

The project has unintentionally, but positively, created a new opportunity. BNIM and the Harkin Institute are partnering to create a guide to inclusive design. It’s in a draft form now, but when it’s done, other building designers will be able to use it as a guide to universal design, beyond what it is legally required.

The new space will also have a gallery showcasing the work of Harkin and his wife, Ruth. Anyone from the public will be able to learn from it and the various programs planned to educate others about the advancement of people with disabilities. A main goal is to eliminate barriers to employment.

“The first step is don’t prejudge what a person can or cannot do,” Jones said.

What Iowa has to gain by employing more professionals with disabilities

According to data from the Office of Persons with Disabilities, just over 349,000 Iowans in 2017 reported having a disability — representing 11.3% of the state’s civilian, noninstitutionalized population. The number of Iowans between the ages of 18 and 64 with a disability who were employed in 2017 was 77,746, according to the agency.

Reach out

Contact the Harkin Institute:

Amy Bentley, policy director

515-271-3591

amy.bentley@drake.edu

Contact Iowa Vocational Rehabilitation Services:

Michelle Krefft, director of business services

515-664-7854

michelle.Krefft@iowa.gov

Emily Barske Wood

Emily Wood is special projects editor at Business Record. She covers nonprofits and philanthropy, HR and leadership, and diversity, equity and inclusion.