The links between unstable housing and health

Children and their caregivers who live in unstable housing situations are more likely to have health-related issues than their more financially stable peers.

That was keynote speaker Stephanie Ettinger de Cuba’s main message at Polk County Housing Trust Fund’s recent Housing Matters Symposium.

“Families struggling to pay rent or are being evicted experience [poor health] in both the children and their parents,” Ettinger de Cuba said. “They are not getting the attention they need because they cannot afford it.”

Ettinger de Cuba, who grew up in Iowa City, is executive director of Children’s HealthWatch and a research associate professor at Boston University’s School of Public Health. She has spent more than 20 years studying the social factors that affect children and their families.

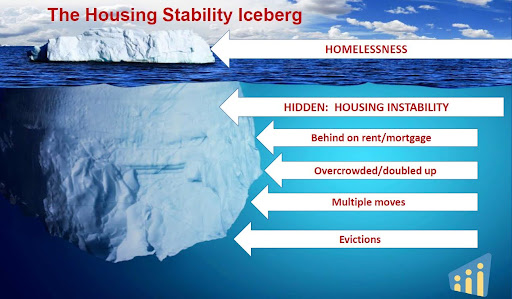

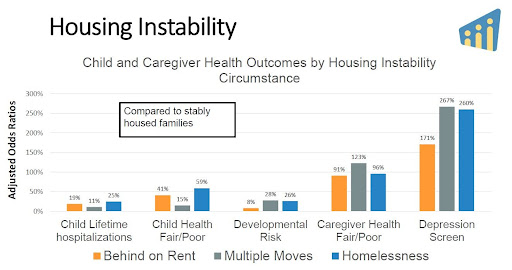

Children in unstable housing environments – behind on rent, moving frequently or experiencing homelessness – are more likely to be hospitalized, in poor health and have cognitive impairments than those whose families don’t struggle financially, Ettinger de Cuba said during her keynote address. The children’s health problems likely will continue into adulthood, she said.

Children whose families struggle financially likely live in unsafe housing environments, exposing them to lead-based paint, asbestos, radon and mold. Children exposed to asbestos tend to have high incidences of asthma and other respiratory illnesses; exposure to lead can damage the nervous system, especially in unborn children, Ettinger de Cuba said.

“If children are too sick to attend school that leads to learning loss,” she said.

Families who struggle to pay rent don’t have money to pay for healthy food, which can lead to health issues including diabetes, Ettinger de Cuba said. Neighborhoods where housing is located can also affect people’s health, she said.

Poor housing quality also affects mental health, especially in caregivers, Ettinger de Cuba said.

“Caregivers – mostly parents – who live in poor quality housing are more likely to be depressed, which in turn leads to disconnection from key support systems like schools, teachers, pediatricians.”

Solutions to the housing problem exist, including providing programs that bridge the gap between a families’ income and housing costs, Ettinger de Cuba said. One program, known as guaranteed basic income, provides unconditional, recurring cash payments to individuals or families to help meet their basic needs. The payments supplement, but don’t replace, existing social safety net programs, she said.

Since 2017, more than 150 guaranteed income programs have been launched in the United States, Ettinger de Cuba said. One of the programs is UpLift, a pilot program in Polk, Dallas and Warren counties that concluded in April.

“There’s a lot of evidence to support guaranteed income programs,” Ettinger de Cuba said.

People in the programs have “improved mental health, reduced anxiety, less stress and depression and increases in their emotional well-being and hope. … And hope is so important. If you don’t have hope, you cannot plan for your future.”

Kathy A. Bolten

Kathy A. Bolten is a senior staff writer at Business Record. She covers real estate and development, workforce development, education, banking and finance, and housing.