Harvest Academy building therapeutic community south of Des Moines

Residential work program focuses on voluntary rehabilitation, preventing incarceration

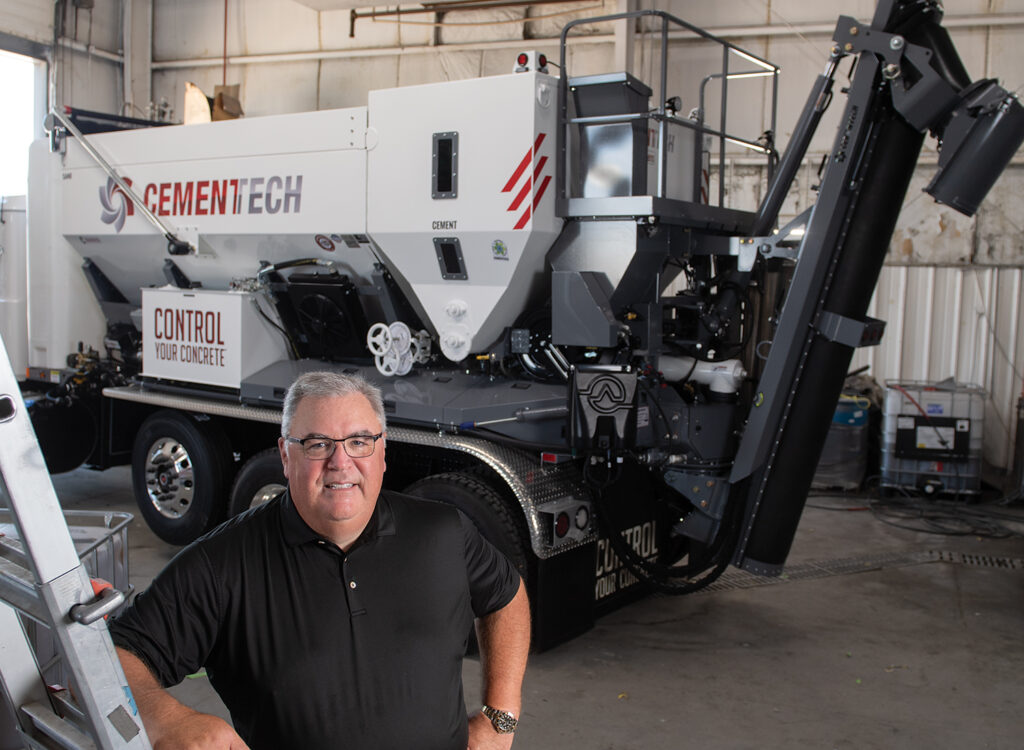

For 16 years, Tim Krueger was in charge of the financial operations for one of the world’s largest sunglasses manufacturers, Maui Jim Inc.

In 2012, however, Krueger retired early from the corporate world and turned his business skills toward building a nonprofit organization with a mission of helping adults with criminal histories or former drug use who wanted to turn their broken lives around. The University of Iowa alumnus returned to the Hawkeye State in 2018, and late last year launched Harvest Academy just south of Des Moines.

Krueger’s passion for rehabilitating individuals through the “therapeutic community” model was sparked after meeting a former federal prison guard in Peoria, Ill., who encouraged Krueger and other business professionals to volunteer with local high school students who had become involved in gangs.

“I started by volunteering in the suburban high schools, which didn’t have as much trouble with gangs, but after several years I started going to work in the inner cities,” Krueger said. “So I just got very interested in helping people who were struggling in life.”

After leaving his corporate position, he had the opportunity to work with the Delancey Street Foundation in San Francisco, which operates residential programs for people who are at risk of jail or prison, but who were willing to work on changing their lives. “That was my first exposure to [the type of program] I was envisioning,” he said.

Krueger subsequently reached out to the Other Side Academy, a therapeutic community in Salt Lake City, where he became part-time CFO — and spent several years learning the business from the ground up.

The therapeutic community model is based on a minimum two-year program in which participants live and work on a small campus community — in Harvest Academy’s case a 10-acre rural property.

“We’re trying to get [the students] into that mindset that when you give, you get,” Krueger said. “A lot of them have never had that opportunity — they have just been trying to survive in a tough world.”

While in the program, they’re also employed by small businesses operated by the nonprofit. The first year of the program is heavily focused on behavioral changes, while the second year emphasizes vocational training along with continued attention to good behavior.

After two years of preparatory work in Iowa, Harvest Academy in December enrolled its first students for the same type of live-in working community. Residents voluntarily apply by writing a letter expressing their desire to turn their lives around and commit to spend at least two years living and working in that community — which in some cases means only limited visits with their partners and children.

“We’re aware of about 15 of this type of therapeutic communities around the world that follow the therapeutic community method, which is really just highly accountable, almost what you would think of as a farm family,” he said.

The model is much like having a highly disciplined, hardworking father and mother who expect a lot from their “kids,” but also know that the students — all adults — are going to mess up and make mistakes, Krueger said. And they also come to understand that there will be more work or other consequences as a result of poor behavior.

Launched with the support of philanthropic contributions by several prominent Iowa families, among them Ankeny business owner Walter Lauridsen and Hawkeyes head football coach Kirk Ferentz, Harvest Academy aims to become financially self-sustaining over time.

The initial investment was used in part to purchase a 10-acre parcel of rural property in Warren County north of Indianola, which has a ranch-style house that has since been remodeled and furnished to sleep up to 18 students, along with two live-in staff members. The startup capital will also help to cover initial operating losses until the businesses get into the black, Krueger said.

An integral part of Harvest Academy’s training regimen for its residents will be operating several businesses that will employ its students, the first of which is a moving company, Harvest Academy Movers, to be followed by a construction firm. Krueger also hopes to secure in-kind contributions, sponsorships and partnerships from a broad range of Central Iowa businesses.

The students will also grow much of their own produce at the property. The nonprofit has formed partnerships with the Food Bank of Iowa and St. Vincent de Paul to supply food items for the students, which will be stocked at a food pantry the students are building in a small outbuilding on the property. Working with the food pantries will enable Harvest Academy to keep its food costs to a minimum, Krueger said.

Additionally, a small office space in the headquarters building that was recently completed next to the existing residence will be used by students to take bids for jobs for the operating companies, as well as solicit corporate donations from Central Iowa companies. That process will also help the students to gain telephone and sales skills and enable them to get the word out about Harvest Academy, Krueger said.

Principal Financial Group has already provided some of its used office furniture for that space, he noted. Other supporters include Austin Palmer, chairman of the Palmer Group in West Des Moines, whose family along with another family donated an 800-book library for the academy’s house, and Paul Juffer, managing partner of accounting firm LWBJ, who chairs Harvest Academy’s board.

The moving company is based on those that are operated by two therapeutic communities in Salt Lake City’s inner city — the Other Side Academy and Red Barn Academy.

Net profits from the business operations will be plowed back into the academy to make it self-sufficient. The students do not pay any fees to be in the program, nor do they receive any pay other than their room and board during their time at the academy. “We look at it like you get a scholarship to a leadership academy,” Krueger said. “We can really look at this as your leadership boot camp — you’re here to really be the best version of yourself.”

During the last phase of the program, known as Re-Entry, the students begin working for an employer for three months in a field they want to pursue. Their pay is held in trust by the academy during this period and then given to them once they graduate.

The academy’s discipline and behavioral modification model is built around a system called the three P’s — the pull-up, the pass and play the game. (See info box.)

“That process really helps them become emotionally intelligent, because they’re hearing about themselves, and they’re sharing what they see about others. If you think about what they learn on the street, there’s a kind of code of what they call loyalty, which is kind of a lie. … What we really drive home is, ‘You’re here to help save Joe, to help him be that person he can be. Don’t let him get away with anything.’”

‘Eye-opening’

Braedon Dowty, the program director for the academy, is a graduate of a therapeutic community in Arizona called the John Volken Academy, as is another staff member, Mike French. After Dowty was hired last summer, Harvest Academy approached numerous judges, sheriffs and defense attorneys to educate them about the program, and invited about three dozen officials to Salt Lake City to see the programs.

Polk County Sheriff Kevin Schneider, who toured the Other Side Academy in Utah, said he was impressed by the program. “They have some very tough standards,” he said. “It’s run by previous inmates, and they’re tougher on their own than any social worker or probation officer would be.”

The sheriff’s department allows Harvest Academy to work with the Polk County Jail and the courts locally to review for inmates who are qualified to apply for the program, Schneider said. Harvest Academy also works at a broader level with Polk County’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, which includes representation from across the criminal justice system.

“Anytime we have a good alternative to jail for people who don’t need to be in jail and they have some good talents or inputs for the community, that’s what we like to do,” he said.

Dave Button, Indianola’s police chief, also toured the Other Side Academy at Krueger’s invitation.

“‘Eye-opening’ would be the way I would describe it,” said Button, who has been in law enforcement for 28 years, the last eight as police chief in Indianola. “The [criminal justice] system we have right now is just not working. It’s not uncommon for us to run into second- and third-generation criminals.”

After visiting both the Salt Lake facility and then Harvest Academy as it began operating, Button could clearly see the program was having an impact. “You can see it in their eyes — they light up when you come to visit them,” he said.

Because he has an English degree, Button was invited by Krueger to provide some pointers to the Harvest Academy students on writing thank-you notes. “I can guarantee you, none of these guys had ever written a thank-you note before,” Button said.

The program’s family atmosphere seems to be part of its effectiveness. “They really mesh together as a unit,” Button said. “And they’re quite respectful of me as a law enforcement officer, which is really refreshing. … I definitely can see where the program would benefit some of the people here in Indianola, and I would happily steer them in that direction.”

Button said he hopes the academy succeeds in growing and becoming a model for more programs like it in Iowa. Currently, “there’s nothing like it in the Midwest,” he said. “I think the closest program like it is in Denver.”

The police chief credited Krueger, who has been a friend of his for a number of years, for a lot of hard work in reaching out to people to make the academy a reality.

“For a guy who’s retired, he puts in a ton of hours,” Button said. “I’m very optimistic it’s going to succeed. I think other people from the Midwest will come around and want to see it.”

Although the program is all-male currently, there are plans to also accept women after the initial two years, Krueger said. The goal in the first year is to build enrollment to about 15 to 20 students.

“And then hopefully our moving company will be up and running with at least two to three trucks,” he said. “On our construction side, we’ve already done some contracting jobs where we are a subcontractor under some lead contractors.”

How can businesses get involved? A first step may be to come out to meet and have lunch with some of the students, Krueger said. “It really helps you to see that this program is different. You’’ll see no one’s standing around, no one’s sitting watching TV. There is some free time, but it’s focused.”

From Krueger’s perspective, it’s the most fulfilling work he’s ever done.

“I was kind of frustrated” seeing societal problems and not having a way to address them, he said. Stepping away from the business world to run a nonprofit, “it’s awesome, he said. “It’s needed.”

What are the 3 P’s?

The pull-up:

Correcting inappropriate behavior or attitudes, such as: “Hey, Joe, we don’t do that around here. Check yourself.” An example would be if a student did a poor job cleaning a bathroom while on the cleaning crew or their attitude is negative. And the student is supposed to respond by simply saying, “Thank you.”

The pass:

Whenever a staff member “pulls a student up,” that information is passed along to the rest of the staff. If it’s a minor incident, it may just be passed to the student to correct the behavior.

Play the game:

This refers to twice-weekly meetings in which the residents discuss the issues they’re having with other residents in which other residents can jump in to provide feedback about their attitudes or behavior. As a consequence of the behavior, someone might get assigned a few more hours of community service.

A student’s perspective

Ryan, who is among the initial four students in the program, said he is grateful for Harvest Academy as “a great opportunity for people to get their life back together, to be the best version of themselves.”

“Growing up here in the Des Moines area, I really didn’t have too many figures I could look up to,” he said. “So the crowd that I stuck into really wasn’t the crowd that was the best for me.”

He’s committing to two years in the program so that he will really change, not only for himself but for his kids, whom he wants to see again — and he wants to be a father they can look up to, he said.