‘Now or never’

Officials hope to put a charge into Iowa's education system with STEM initiative

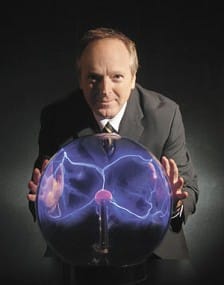

Jeff Weld knows he might sound a bit overdramatic, as if he’s spitting out hyperbole when it comes to the importance of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

But in serving as the executive director of the Governor’s STEM Advisory Council, Weld – also the director of the Iowa Mathematics and Science Education Partnership – is charged with heading up an initiative during what he and others feel is a crucial moment in the state’s history.

“I am truly convinced that we’re going to get one shot to do this well, and (Gov. Terry Branstad and Lt. Gov. Kim Reynolds) have provided this shot,” Weld said. “We’ve got presidents of universities, CEOs, teachers, students and parents very excited. When they’ve assembled that kind of a group to get this kind of a challenge addressed, if we fail to deliver, they may never come back to the table. Our state will suffer irreparably, and likely permanently. So the pressure is significant.

“It is now or never.”

The challenge: The number of STEM-related jobs in the state is projected to increase by 16 percent between 2008 and 2018. Only 11 percent of Iowa’s 2011 ACT test-takers scored college-ready in both math and science and expressed an interest in STEM majors.

“If we don’t address this in a significant fashion right now, we’ll be faced with a deficit situation in the future,” said Paul Schickler III, president of Pioneer Hi-Bred International Inc. and a member of the council’s 13-member executive committee.

The potential solution: Branstad has put together an advisory council of 40 educators, business leaders and government officials in an effort to get Iowa’s schools, colleges and universities prepared for the challenge. The executive committee within the council consists of a who’s who of leaders in the state, including Reynolds, Schickler, the presidents of all three state universities and Des Moines Area Community College President Rob Denson.

“There’s fire in the belly,” Denson said.

The plan

The council first met on Halloween day last year at the Science Center of Iowa, and the executive committee has met six times since.

The council broke up into seven working groups to present action plans that will be brought to Branstad for policy recommendations. The rough drafts of the plans were given to the executive committee on March 12. From there, the council’s goal is to boil the plans down to a consensus singular action plan by the fall.

The plans are designed to identify concrete ways that schools can better teach STEM subjects and businesses can help schools prepare the next generation of the work force. On a macro level, Weld’s goal is to put every school on an equal playing field. For example, it’s not fair, he said, that someone born in Pella has the advantage of using Pella Corp. and Vermeer Corp.’s resources, while a student born in another town might not be so lucky.

“We’ve got a lot of talent doing interesting things already, but it’s far from enough,” Weld said. “The efforts of the Technology Association of Iowa, the efforts of a certain school, the efforts of a teacher in Pella – that’s not enough. Everybody has to be on top of their games.”

Why STEM?

Businesses must have an educated work force to attract from, which includes people with a high level of interest and education in STEM, Schickler said. That goes for businesses such as Pioneer, which has a lot of jobs that would traditionally be viewed as STEM-related, and businesses such as Principal Financial Group Inc., which might not come to the forefront of someone’s mind when thinking of STEM.

Even if a company’s profile doesn’t directly call for extensive knowledge of science, technology, engineering or math, every organization needs skills in multiple disciplines, he said.

Weld adds, “I cannot think of a company that doesn’t have a STEM necessity.” Likewise, most jobs require some knowledge of a STEM discipline.

How to get involved

“This whole thing is nothing without the business sector,” Weld said. “Its purpose is largely driven by the interest of the business sector.”

Because money will be needed to implement programs and changes, Weld is confident that the Legislature will need to see private investment in order to pass and enforce some of the changes that come out of the council’s recommendations.

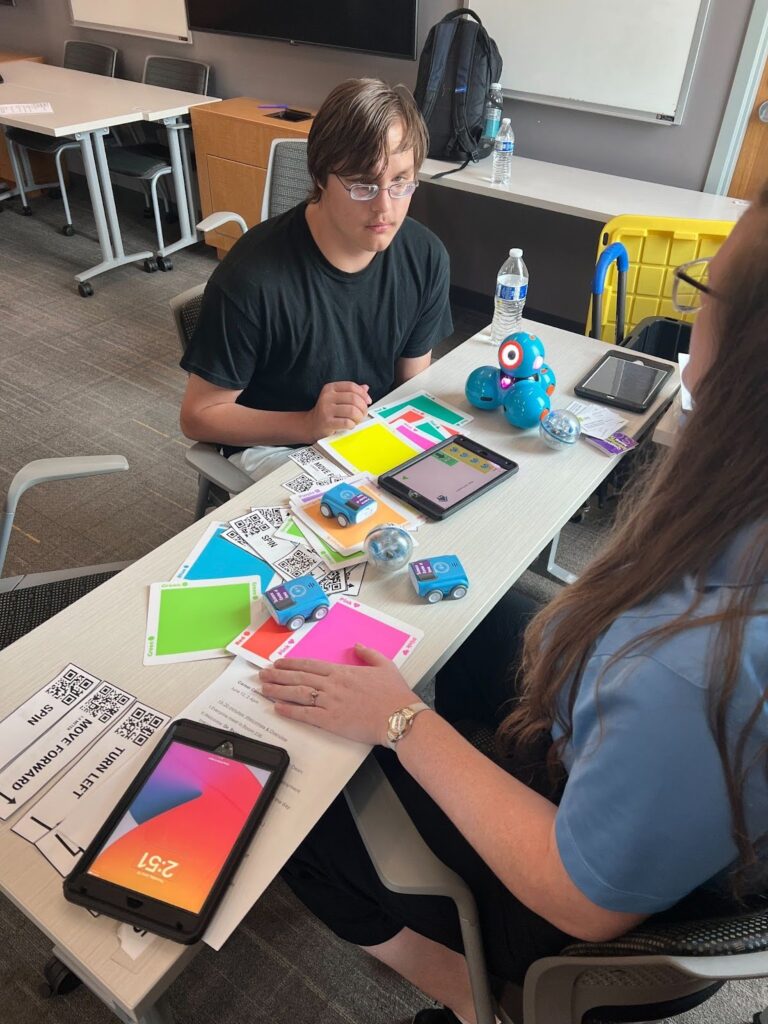

Beyond monetary support, Weld doesn’t want to see businesses just write a blank check; he hopes to see involvement. That could be in the form of things that are already happening, like student internships and short summer “externships” at businesses for teachers, or businesses setting up STEM programs in schools. Some businesses already do those things, but Weld estimates that only about a dozen companies statewide are closely engaged with schools.

The council is also splitting the state into six regional networks to better focus on STEM initiatives at a local level. Each will have a hub, which could be a school or a business, to serve as the center of operations. Denson at DMACC said he’d like to see a business or an association of business organizations to take the leadership role in the region that includes Des Moines. Weld said he’s received interest from businesses, colleges, museums and high schools throughout the state to be hubs.

Mike Ralston, president of the Iowa Association of Business and Industry (ABI), said he has seen mixed levels of support so far among the businesses that ABI represents. His organization is trying to make sure that smaller companies, especially manufacturers, are involved in the initiative in the same way that Pioneer is.

“Business people are pretty smart about their business, and they know there is an initiative that will help them get better employees,” Ralston said. “They’ll see that as something they want to do.”

Challenges

Money: In today’s political climate, spending extra public money on anything can be a hard sell. Weld hopes a lot of priorities can be funded through a redistribution of funds that are already going to education, as well as federal grants and business donations.

Politics: The council’s recommendations will ultimately go to Branstad, and some proposed initiatives will have to be approved by the Iowa Legislature. When presented with a proposal, “the governor is going to have a decision to make. Hopefully we’ll all be in on that decision,” Weld said.

Dealing with change: Iowa has a good history of education, Schickler said, and there could be some reluctance to step back, look critically at the education system and make aggressive changes.

Key STEM statistics

STEM jobs in Iowa are expected to climb from 57,830 in 2008 to 67,330 in 2018, a 16 percent increase. Post-secondary education will be required for 91 percent of those jobs.

In the 2009 National Assessment of Educational Progress, 34% of Iowa eighth-graders scored proficient on the math test and 35% scored proficient on the science test.

Fewer Iowa college students major in STEM fields than the national average.

1% of Iowa’s 2011 ACT test-takers scored college-ready in both math and science and expressed interest in STEM majors.

Of the new jobs, 52% will be in computer occupations, 24% in engineering fields and 15% in life sciences.

Sources: Statistics compiled by the Governor’s STEM Advisory Council from Georgetown University, Change the Equation, Battelle Iowa Studies and the Alliance for Science and Technology Research in America

For more information, go to www.iowamathscience.org/exec_comm

To see the rough drafts of each of the seven working groups, go to http://tinyurl.com/7sdvrvy