University Research: ‘Nanotech in our hands’

Professors tackle way to marry nanos with gene detection

KATE HAYDEN May 9, 2018 | 1:27 pm

3 min read time

710 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Innovation and EntrepreneurshipOVERVIEW

At a national level, Simpson College professors Derek Lyons and Aaron Santos had seen promising nanotechnology research fail to deliver usable solutions for practical problems.

“Nanotechnology has been this dream that has never come true,” Lyons, a biochemist, said.

“It’s a backbone of all of modern biotechnology, being able to modify DNA, because you can get a new trait. But you’ve got to be able to detect what was there,” Lyons said. “The entire ag industry is running this for GMO corn — to know if it’s genetically modified, you need to check the genetics. … It’s such a broad thing, but it’s been done in such an isolated way that it takes a biochemist to test for genetics.”

METHOD

Research by Lyons and physicist Santos started six years ago and stalled for more than five years as the two struggled to break through challenges, Lyons said.

“We were very bitter about where the nanotechnology field was at and how many applications come out of it,” Lyons said. “Nanotechnology was starting to associate with failure and empty promises, like the flying car. Everybody says they’re working on it, and you never get it.”

Nationally, researchers could demonstrate what nanotechnology was — a California researcher created the world’s smallest smiley face way back in 2006 by nano-assembling DNA strands — but the process was costly and couldn’t do much more beyond forming shapes.

Lyons and Santos started by taking microscopic images of nanoparticles as the particles “float” in the organic matter sample. As they float, the particles begin to attract and build structures held together by DNA strands.

“Smiley faces don’t cure cancer. So we said, ‘What do we care about, and what could we solve with this?’ ” Lyons said. “We had to pick something we knew well, and we had to pick something we had support for in the area.”

Lyons and Santos turned to genetic testing — a cumbersome and time-consuming process that is used in everything from soybean fields and wildlife management to hospital laboratories and international trade regulations.

Traditional genetic testing takes enzyme samples from a piece of genetic material and tests them in a chemical solution. “It’s a lot of training. It’s a bachelor’s degree at Simpson,” Lyons said.

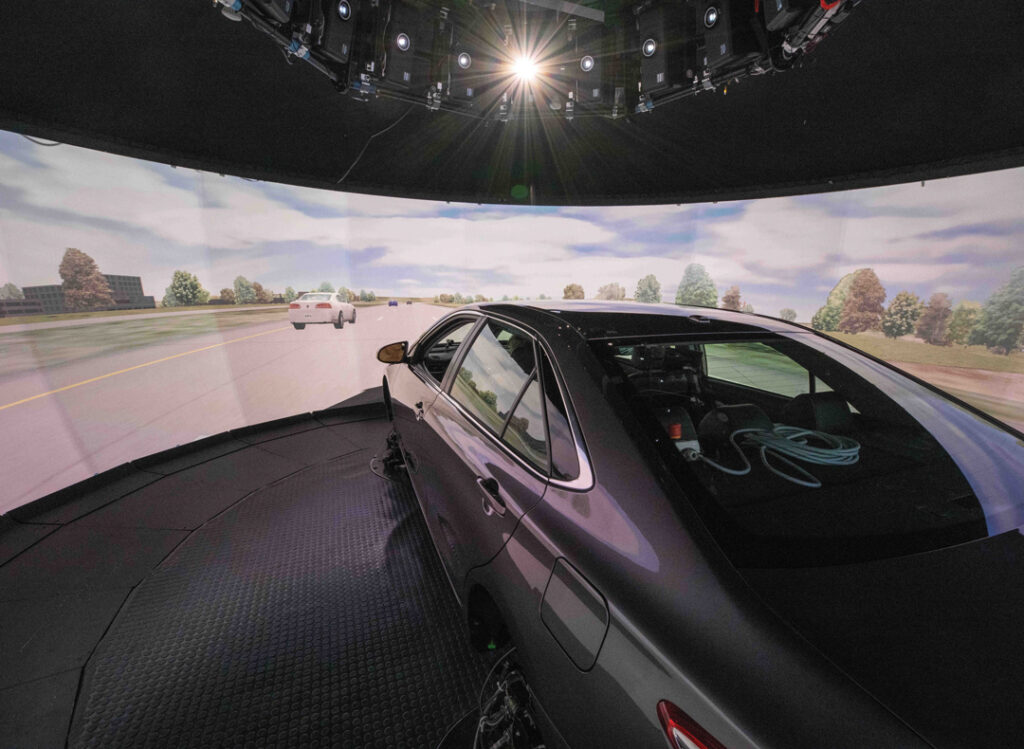

Once the researchers identified gene detection as a possible application, research picked up the pace. Lyons and Santos built the first prototype, a foot-long metal box stuffed with wires, that walked away from the old genetic testing model of chemical reactions based on enzymes. Leaving chemistry behind made the testing process faster for users, Lyons said.

“It looked more like a metal brick than a nice, usable device,” Lyons said. “But something that we’ve learned along the hard way is you should fail a lot, but do it quickly. We did not do it very quickly for a long time.

“There’s a finite amount of things that you can do wrong, and we’re not scared to try all of them and do all the wrong things to get to the thing that works.”

Despite neither researcher being an electrical engineer, they soon condensed the “metal brick” into a device about the size of an iPhone 6, with a sample card that can test up to 200 genetic material samples at once for genetic traits.

RESULTS

In summer 2017, Lyons and Santos worked with the Simpson-based venture capital corporation Emerge Foundation to found DNP123: the parent corporation owned by Santos and Lyons that owns products like ExpresSeed, which is currently piloting in agricultural industries.

“We really wanted to see our idea take physical form, and we’d been in nanotechnology for too long where all we saw was just looking at theoretical pictures,” Lyons said. “It felt so good to have nanotech in our hands, instead of on a piece of paper.”

ExpresSeed is learning how to customize the product to each specific industry Lyons and Santos seek to serve. DNP123 received a Proof of Commercial Relevance loan from the state of Iowa to use for customer discovery of ExpresSeed’s handheld system.

“For us, the most fun thing about this is to finally see nanotechnology have an application,” Lyons said.

TO LEARN MORE

Read more about their research and ExpresSeed at these links:

– www.dnp123nano.com

– www.expresseedgenetics.com.