University Research: Wind turbines alter crop field climate

Iowa State University researchers report that the wind turbines that dot Iowa’s landscape — especially in northern Iowa ? may help crops growing around them

OVERVIEW

Iowa is the nation’s top corn grower. When wind energy boomed here, farmers began signing leases to provide a small patch of land for each of the hundreds of turbines that can make up a wind farm. They knew going in that they could still plant crops right up to the turbine site. There was some discussion about noise and possible bird deaths, but not much about how the wind turbines would affect the crops, if at all.

METHOD

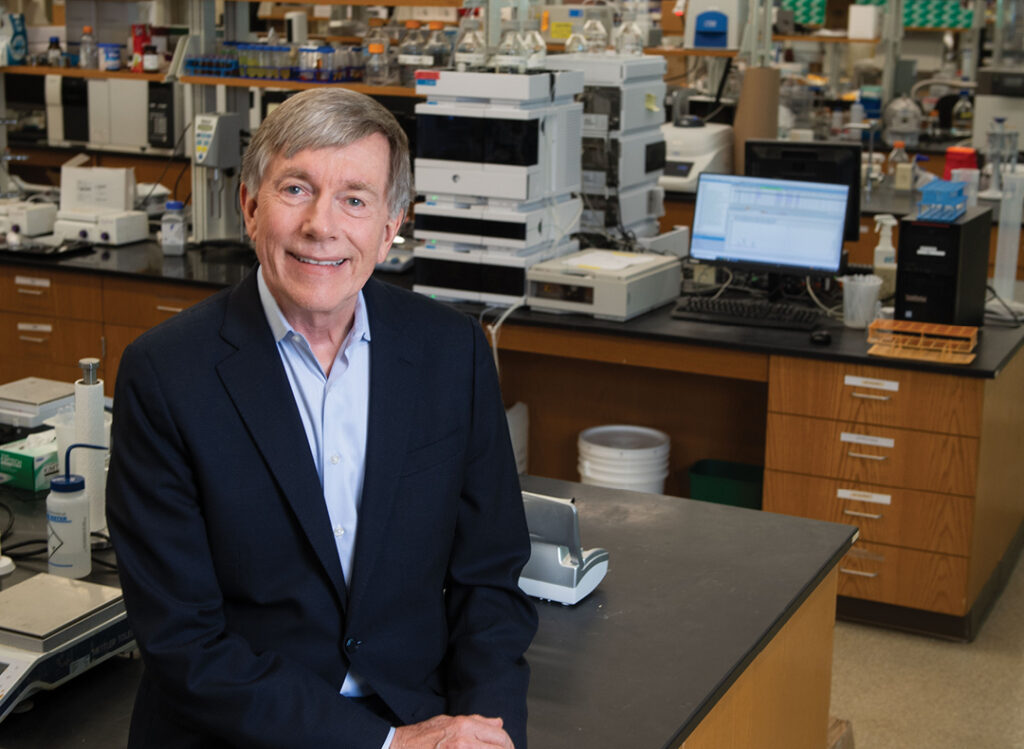

Iowa State agronomy professor Gene Takle led a team of plant and soil scientists and extension specialists who have looked into this question since 2009. Would the turbines change the microclimate in the fields?

“It’s unusual because we’re continuing the previous land use and we’re adding another,” Takle said in an ISU report. “We’re sort of double-cropping because these can be thought of as two forms of energy production. The Chinese do this when they plant soybeans in between horticultural crops. We’re planting turbines.”

Scientists have studied moisture levels, winds, relative humidities and other weather data, and are expanding to wind pattern research now.

RESULTS

Takle said wind in a field typically carries moisture away from the crops, sending it into the atmosphere and bringing cooler, drier air downward. When night falls, winds drop and the land cools.

“The biggest changes are at night, and that’s because during the day there’s a lot of chaotic turbulence, just because the sun is heating the surface and the wind is gusty,” Takle said.

“At night when it gets pretty calm, the crop cools down and if it’s a humid night you start to get dew formation. If you add the turbines, it looks a little more like the daytime. So the dew formation is delayed and it may start to evaporate sooner.”

Because turbines could shorten the damp period, fungus and mold might be less of a problem, Takle reasoned. And harvest could speed along because fall conditions could be drier.

Wind turbines tend to push warmer air down, resulting in higher temperatures near the surface.

“Satellites can measure surface temperatures and you can see little dots across the state of Iowa and locate every wind farm because they’re slightly warmer than the surrounding area. So we know it has an effect that’s large enough to be seen there,” Takle said.

The turbines even help the crops thrive, pushing air down, which releases a store of carbon dioxide just under the surface. As we all learned in our science classes, plants use carbon dioxide and water to form glucose to store energy. And the wind tends to move plant leaves, letting more light hit the bottom of the plant and the ground.

The warmer conditions at night are a challenge, because corn typically cools off at night, sending some of the carbon dioxide back to the atmosphere, Takle said.

That’s challenging news for crops that already have faced a long period of warmer nights, even without turbines around. In fact, crop yields can drop.

“Nighttime temps have been going up over the last 40 years and are becoming a limiting factor for crop yields,” Takle said.

On balance, the turbines appear to help crops, though not enough research has been done to pin down a precise change in yield.

“We measured increased carbon dioxide uptake during the day, but an increased respiration at night,” Takle said. “But over the course of the day there was more uptake. So as far as the impact of the turbines on the carbon dioxide processes and the photosynthesis process in the near vicinity of the turbines, it’s a net gain.”

His team would like to look at the result of wind movement through a farm as it slows and then tends to rise, which could create clouds if the air is warm and moist, and potentially rain.

“Are wind farms a preferential location for cloud formation or something that’s going to provide more rain in an area beyond the wind farm? We don’t know. We have some preliminary measurements that suggest that this is a real effect. Theoretically, you say, ‘Yes, there should be an effect,’ but is it large enough to be measured or to be important?” Takle asked.

The researchers don’t have a good answer about whether grain yields change any more than natural variability would dictate, Takle said, but they hope farmers will improve their observations of crops near turbines so measurement strategies can be fine-tuned.

The ISU team now is studying how wind disruptions around turbines could affect how much power turbines produce. The researchers installed a sonic radar to measure winds above turbines. The team will also look to improve forecasts, because wind farm owners have to sell energy a day before production on the regional market, said Takle, who retires this month.

The scientists also are looking into what Takle describes as the failure of a 60-year-old theory on how air moves near the ground. They will take high-resolution wind speed measurements at 13 spots up and down some turbine towers. That work will also feed into improving forecasts of energy production.

TO LEARN MORE

Read Gene Takle’s bio:

– http://www.meteor.iastate.edu/faculty/takle/

Read a news release on the project:

– https://bit.ly/2JfN9or

Read our story about Takle’s search into climate change and agriculture:

– https://bit.ly/2qPZMjq