A caregiving revolution

How Iowa companies are responding to employees' needs as caregivers

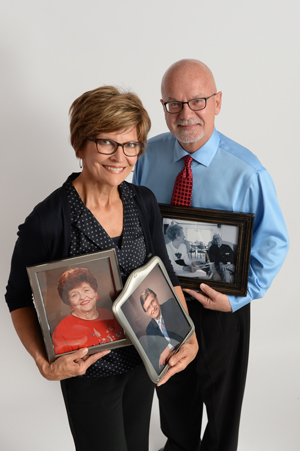

The first time Terri Hale realized her aging father needed some help from her, she remembers struggling to accept that he was growing older.

Her father was in his late 70s a decade ago when he began needing some assistance from her because of memory issues, said Hale, who works at Principal Financial Group Inc.

“I remember at the time talking to my uncle, his younger brother, and being just a little bit baffled that he would need some help,” Hale recalled. “It was very difficult for me to accept the reality of the impacts of aging and what it was doing to my dad. To this day I continue to struggle with it.”

Over the past decade, as her role as a family caregiver evolved, she had to transition to a part-time role at Principal so she could spend more time caring for her dad, who is now 85. Her husband, John Hale, cared for his aging mother for several years following the death of his father, and now runs his own consulting firm, The Hale Group, which provides policy expertise on aging and caregiving issues.

The couple is among more than 317,000 Iowans who care for an aging family member. There are more than 34.2 million Americans who provide ongoing care and support for their loved ones on a daily basis.

As Iowa’s population continues to age, workers and families are feeling the pressure to fill the role of caregivers. It’s also prompting employers to step up to provide workers with the flexibility to take care of aging family members.

By 2030, 22.4 percent percent of Iowans will be 65 and older, up from 16.3 percent currently, according to the federal Administration on Aging. Many of them are receiving support and care from their boomer children, who, as they age, likely will need long-term care services themselves. The aging agency projects that 70 percent of people 65 and older will need some form of long-term services and supports.

Demographically, the aging baby boomer generation outnumbers the millennials who are next in line to take care of them, which means a shrinking pool of potential caregivers as we all continue to age. The paid caregiving workforce is also reaching a crisis point because of the inability to recruit and retain the workers needed to meet the growing demand, experts say.

‘A huge commitment’

Caregivers may spend anywhere from 20 to 160 hours a week caring for someone else, said Jim Cushing, executive director of the Iowa Association of Area Agencies on Aging. “It’s a huge commitment; many times it’s a full-time job being a caregiver while trying to maintain a full-time job.”

From an income perspective, caregivers can lose between $304,000 and $750,000 in earnings in a lifetime through forgone promotions, unpaid leave or moving to a part-time status, Cushing said. That figure is based on a study by AARP Policy Institute/MetLife Mature Market Institute/National Center on Caregiving.

Additionally, most caregivers spend a certain percentage of their income on expenses related to supporting the person cared for, whether it’s buying them groceries or simply the cost of ferrying them to doctors, that can run as much as 25 percent of a person’s income, he said.

Caregivers also often face tough choices as they weigh their priorities between career and family obligations. Cushing, who earlier in his career worked for Principal, was on track to move up to higher-level leadership with the company before taking a different position and reducing his hours so that he could spend more time taking care of his parents. “Principal was very supportive when I made the decision to be a caregiver, and I do not regret that,” he said.

How workplaces are responding

In a national survey conducted last year by AARP and the National Alliance for Caregiving, 6 in 10 caregivers reported being employed at some point in the past year while caregiving. Among them, 56 percent worked full time, and on average, they worked 34.7 hours a week.

Most caregivers find they must make changes to their work situation. Six in 10 caregivers surveyed said they had to make a workplace accommodation as a result of caregiving, such as cutting back on their work hours, taking a leave of absence, receiving a warning about performance or attendance, or other such impacts.

Higher-hour caregivers are more likely to report experiencing nearly all of these work impacts.

John Hale, the caregiving consultant, said he sees a growing recognition on the part of the Iowa business community of the need to support family caregivers.

“The challenges these caregivers have are very similar to what younger employees with young children have,” Hale said. “It’s all part of responsibilities in life that employees have that employers need to be supportive of.”

Polly Heinen, assistant director for human resources benefits with Principal, said her company is attuned to the needs of its employees with caregiving responsibilities.

“We do have a comprehensive benefits package that’s designed to help employees at all stages of their careers,” she said. “A lot of times it comes down to how we we help them stay engaged with work.” For instance, Principal allows employees to work from home or other remote locations if a person needs to be available to help out a parent, Heinen said.

“We also have a great paid time off policy; a lot of times those (benefits) are combined. So all of a sudden if you get a call that mom’s not well, they may take a day of PTO to fly down, and then work remotely from that location,” Heinen said. The company also has a personal leave policy in which people can take up to 12 weeks where they can be working part time or combine that with paid time off, with a supervisor’s permission, she said.

In the national caregiving survey, more than half (56 percent) of those employees surveyed said their supervisor at work is aware of their caregiving responsibility.

And just over half of the workers surveyed said their employer offers flexible work hours or paid sick days. Fewer working caregivers, 23 percent, said their employers offer employee assistance programs or telecommuting (22 percent). Nearly all workplace benefits are more commonly reported by caregivers working full time.

Heinen said one of the most popular benefits for caregivers has been a recurring class conducted by the Hales, who a year ago were asked by Iowa Public Television to moderate a call-in show on the topic. That led to Principal asking them to host a class for employees.

“The first one was so popular that they scheduled a second and third one,” Terri Hale said. The couple conducted its fourth class in August.

There are a number of resources outside the workplace that people can use to find help. Two key statewide resources coordinated by the Iowa Association of Area Agencies on Aging are LifeLong Links and the Iowa Family and Friends Caregiver program. (See page 9 for more resources.)

Caregivers are increasingly reaching out to these programs, Cushing said. “There’s been kind of a shift over the past three to five years where maybe it was the individual or their spouse calling, but now it’s the kids calling,” he said.

“Many times it’s a crisis situation where mom fell and broke a hip,” Cushing said. “She’s been in rehab and now she’s coming home and we don’t know what to do. Other times people call us and say, ‘My mom and dad aren’t doing as well, but we just don’t think they’re ready for a nursing facility. So what do we do?’ ”

Proposed legislation would assist caregivers

Tips for caregivers

During the class she offers at Principal Financial Group, Terri Hale encourages employees to examine their own thoughts and feelings about their aging parents as a step toward understanding how the situation is affecting them. “If you don’t, it’s going to affect how well you care for your parent,” she said. “So have compassion on yourself.

“And second, have compassion on your parent, because as hard as this is for you, it’s harder on them,” she said. “They’re going to have a lot of feelings; they’re going to be afraid a lot, and that may come out as anger. Recognizing that, you can be better prepared to deal with it.”

Another important step is for the caregiver to ensure he or she has support to lean on. “And don’t always rely on your spouse, because this wears them out, too,” Hale said. “And absolutely call Lifelong Links (the statewide resource program).”

Another piece of advice Hale gives: Take your parent to the doctor as soon as you start to see health issues.

“Go with them and be their advocate because often they’re not going to say what’s going on,” she said. “There are questions they probably are not going to ask. And there are times you need to push and ask for further treatment. And it’s good because you then develop a relationship with the doctor, and later he helped me to be an ally for my dad.”

Although John Hale’s professional world revolved around public policy in caregiving and aging, he found himself personally unprepared to deal with his mother’s dementia and the decisions that required.

“I spend a lot of time on these issues, but even with all that background this was still a new world for me,” he said. “One of the lessons that came out of this and that has been reinforced over and over — we have simply got to change the way we approach people aging and caregiving challenges. While it’s easiest to assume that everything’s going to be fine and be in a state of denial, life doesn’t usually happen that way.”

The couple strongly recommends that caregivers begin thinking about their own journey into later life. How prepared are you for the time when you’re going to need some help? Do you have the financial resources; do the people closest to you know your desires?

“One of the most difficult things people experience in life is the loss of independence,” John Hale said. “I think we’re all prepared for death, but what we’re not prepared for is the loss of independence. What we don’t plan for is decline. We have to do a better job of having that conversation, which is difficult to have, whether it’s ourselves with our parents or ourselves with our children.”

By the numbers

- The majority (60 percent) of caregivers are female. Eight in 10 (82 percent) are taking care of one person. They are 49 years old, on average.

- A majority (85 percent) provide care for a relative. About half (49 percent) care for parent or parent-in-law One in 10 provides care for a spouse.

- The typical care recipient is female (65 percent) and 69 years old.

- Nearly half (47 percent) of caregivers care for someone 75 or older.

- About half (48 percent) of care recipients live in their own home Higher-hour caregivers are more likely to live with their care recipient.

Source: “Caregiving in the U.S.” report conducted in 2015 by the AARP Public Policy Institute and the National Alliance for Caregiving

Online Resources

LifeLong Links: www.lifelonglinks.org or 866-468-7887

Iowa Friends and Family Caregiver Program: www.iowaaging.gov/family-caregiver

ReACT Employer Resource Guide: www.aarp.org/react

Employer Best Practices (EEOC): www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/caregiver-best-practices.html

Iowa Association for Area Agencies on Aging: www.i4a.org/

AARP Prepare to Care Guide booklet: http://bit.ly/2biTKk6