An epidemic of errors?

What’s the real extent and cost of medical mistakes in Iowa?

JOE GARDYASZ Mar 20, 2018 | 7:11 pm

9 min read time

2,253 wordsAll Latest News, Business Record Insider, Health and WellnessHow common are preventable medical errors in Iowa? Are hospitals and doctors taking sufficient steps to prevent medical errors? And how much are medical errors contributing to the high cost of health care?

According to a report released in January by Clive-based Heartland Health Research Institute, nearly 1 in 5 Iowa adults surveyed said they have experienced some degree of medical error in the past five years.

In a statistically valid survey of more than 1,000 Iowa adults conducted last summer, 18.8 percent of respondents said that they or someone whose care they were closely involved in was personally involved in a situation involving a preventable medical error.

Moreover, nearly two-thirds of those Iowans who claimed to have experienced medical errors said the health consequences of the error were “serious,” and one-third of those responding affirmatively reported having “serious” financial consequences due to the error.

The author of the report, benefits consultant David Lind, got permission from Harvard University to adopt the same survey methodology that Harvard researchers had used to estimate medical errors in Massachusetts to establish a baseline for Iowa’s share of medical errors.

Nationally, medical errors are estimated to result in serious harm to between 6.6 million and 11.5 million Americans each year, and result in an estimated 250,000 deaths annually, according to a Johns Hopkins study.

A national survey released in September 2017 by the University of Chicago that used a similar methodology as Harvard’s and Lind’s study found that 21 percent of respondents said they had been affected by a medical error, and 31 percent had been personally involved with the care of someone who had experienced an error.

Lind, who for years has surveyed Iowa employers about rising health care insurance costs, decided last year to delve further into underlying causes of skyrocketing medical costs, and identified medical errors as a major contributor.

In comparison with the highly publicized opioid crisis in the United States, which in 2014 claimed approximately 47,000 lives, an estimated 250,000 Americans die each year due to medical errors, Lind said, citing medical error data that he extrapolated two years ago using national figures.

“If that’s not an epidemic, I don’t know what is,” he said. “And we’re spending a great deal of time, energy and money on the opioid epidemic, but I want to make sure we’re not taking our eye off of this other issue that we’re all affected by, whether we are payers, employers or employees.”

Finding a high level of variability in national data on medical errors, he conducted an initial study in 2016 that estimated between 54,000 and 112,000 Iowans could be affected by medical errors annually, and followed up with a survey of Iowa residents in 2017.

“Are errors getting better in our country? I’d like to think they are, but the fact of the matter is we really don’t know for sure,” Lind said. “Part of it is that we have underreporting or no reporting of errors.”

In his report, Lind recommends a two-pronged approach for Iowa to better address medical errors:

• Establish a patient incident reporting system

for patients to report medical errors.

• Institute an ongoing random sampling

process of providers and patients.

‘Great progress’ over past 20 years

Physicians who are deeply involved in patient safety improvement efforts in Iowa acknowledge that medical errors — and sometimes serious harm — can and still do happen. However, they point to systemic cultural changes and significant improvements that hospitals and health care providers have undergone in the past 20 years to address patient safety.

“I think we have made great progress,” said Dr. Tom Evans, president and CEO of the Iowa Healthcare Collaborative. “I’ve been in practice since 1986, so I’ve been around a while. What we used to do and what we do now are completely different.”

Created in 2004 by the Iowa Medical Society and the Iowa Hospital Association, the collaborative was developed to share data and rapidly deploy best practices in quality improvement.

Evans emphasized that physicians and hospital systems are engaged in addressing quality and that good patient relationships and communication are key to accomplishing that.

“If (Lind’s study) helps patients get engaged, then that’s good,” Evans said. “But I think it’s a little misleading because it drives a wedge between the kind of relationship we think we need to have with patients. We want to work together to build systems where harm can’t happen, instead of (sending the message) ‘Don’t go to the hospitals or the doctors that do bad stuff.’ ”

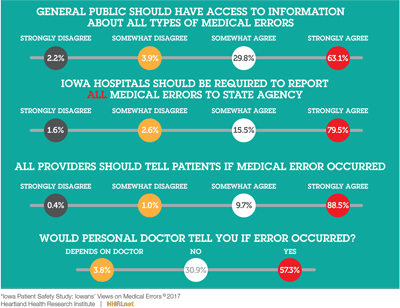

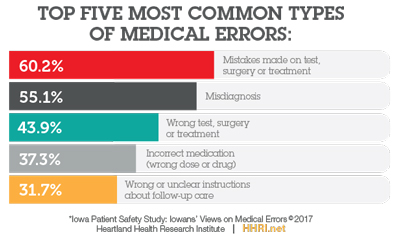

According to the results of Lind’s study, the most common error reported by Iowans was a mistake made during a test, surgery or treatment; 60 percent of those who said there was an error categorized it that way. The second most common error identified was misdiagnosis, with 55 percent saying they’d had a medical problem that was either not diagnosed, diagnosed incorrectly, or was a delayed diagnosis.

Among those who said there were errors, fewer than 40 percent said they were notified by the provider or medical staff about the error, according to the report.

Leapfrog Group, a hospital safety rating organization, says its research indicates that about $8,000 of the cost of each hospital admission is attributable to the cost of errors, injuries, accidents and infections in the United States. According to their ratings, hospitals that have earned A grades for safety have about $1,000 less in medical error costs than hospitals that have a C rating.

Lind said Leapfrog’s figures illustrate the impact that medical errors have on health care costs, “whether it’s through what employers are paying with premiums, what you and I are paying through payroll deductions, and for deductibles that have to be increased as costs increase. So there’s a huge cost associated with medical errors.”

Complaints taken ‘very seriously’

Each year, the Iowa Board of Medicine receives hundreds of complaints about physicians from Iowans, all of which are evaluated and responded to, said Mark Bowden, the board’s executive director. The board’s database includes some 13,000 licensed physicians, about half of whom have active practices in the state.

“We take all the complaints very seriously, but they range from the doctor’s bedside manner to ‘they amputated the wrong leg,’ ” Bowden said. “If we’re doing our job, we’re determining whether a medical error occurred.”

In 2016, the board received 645 complaints and closed out 661 files from the current or previous years, according to the most recent annual report available on its website. The board took 62 public actions in 2016 that ranged from license probation to suspensions, practice restrictions and public penalties.

The board in 2016 filed charges against 24 Iowa physicians involving issues related to their practices in Iowa, or related to adverse actions taken against them by another state’s licensing board. Those charges varied widely, from professional incompetency to improper prescribing, gross negligence and sexual misconduct, according to a summary in its annual report.

Under Iowa law, any cases of harm that could have been caused by medical errors are subject to a peer review by a panel of physicians outside of the board to determine if there were any problems with how the care was delivered, Bowden said. “If so, that’s the basis for the board to move ahead,” he said.

Based on his experience, does the 18.8 percent of Iowans reporting personal knowledge of medical errors documented in Lind’s survey seem accurate?

“I don’t know,” Bowden said. “There may be people that believe an error occurred, but was it based on documented reports, or the belief that something must have occurred? When a patient signs an informed consent for procedures, it can be fairly detailed about what could go wrong, and some of those [when they do go wrong] could be thought to be errors.”

Attorney: Medical community slow to use new law

Russ Hixson, a West Des Moines attorney who specializes in medical malpractice cases, said his practice receives an average of 20 inquiries a week about potential cases. However, it typically refers all but the most catastrophic cases to the Iowa Board of Medicine, he said.

“From a medical malpractice standpoint, they are so costly to pursue that the person would probably spend more than they would be able to recover,” he said. “We’re very selective on our cases; normally we only do catastrophic cases, such as cerebral palsy due to negligence in delivery. Last year we probably resolved about six of those cases, some in the six figures.”

Data from the Iowa Insurance Division provide a snapshot of medical malpractice claim activity. In the 2016 report, more claims were filed for “failure to diagnose/monitor/treat” — 32 totaling more than $1.6 million in benefits paid — than for any other listed alleged cause of loss. The costliest closed malpractice insurance claims were for “fracture/fall” cases, while the costliest open claims were from “pregnancy or birth related problems,” according to the report.

Five closed medical malpractice insurance claims in 2016 were at least $1 million, with the largest paid losses reaching about $1.5 million. Eleven open claims were at least $1 million, with the largest claim reaching about $2.4 million.

In 2015, Gov. Terry Branstad signed the Candor Law, which established a framework for physicians to engage in candid discussions with patients in cases involving medical errors without compromising either side’s position if the matter resulted in a medical malpractice suit.

Hixson, who helped the Iowa Association for Justice draft the Candor bill, said the medical community has been slow in using the new law.

“It does not appear to me yet that the medical side is being educated as they should be on the benefits of Candor,” he said. “And I don’t think insurers or their agents have been educated.”

Hixson said that often when he attempts to initiate the process by sending what are known as invitations to a hospital and physician to invoke the Candor law, he receives an email response from an insurance agent telling him that a medical malpractice insurance claim has been opened on behalf of the physician. By doing that, the agent “may have just prevented their client from using the Candor law,” he said. “So they’re just not being educated on the law. We have a number of agents who don’t even know what it is.”

How transparent?

From the perspective of the state’s trial attorneys’ association, Iowa’s health care providers have a transparency problem, said Andrew Mertens, communications director for the Iowa Association for Justice.

“Iowans file fewer medical malpractice lawsuits per capita than almost any other state in the nation,” Mertens said in an emailed statement. “That is not because Iowans experience fewer errors, it’s because patients are left in the dark.”

Referring to Lind’s survey in which 60 percent of respondents said they were not told by the hospital when an error had occurred, “this is an industry-wide transparency problem,” Mertens said. “There needs to be standardized mandatory public reporting of all medical errors. It also needs to be made easier to hold hospitals and doctors accountable in court when they refuse to follow the standard of care.

“The injuries, deaths and costs of medical errors are preventable, but only if the industry and state lawmakers are willing to make safety a priority,” Mertens said.

From Lind’s perspective, creating more transparency for everyone, not just the patient who was involved, is important. A problem with the current law is that there is no reporting of the medical error beyond that particular patient.

“Maybe patients are notified by the provider about what had happened, but does that really fix the problem going forward for the rest of us to understand the transparency of the medical establishment?” he said. “To me, I think that’s a step forward, but it doesn’t go nearly as far as I would like to see it.”

One of the most important reasons that Iowans don’t report errors, according to the survey results, “is that they didn’t think it would do any good,” Lind said. “I think that says a lot. And 90 percent said that they thought the error was preventable.”

Lind included an additional question that the Harvard study he used as a model did not have: What were the financial consequences of the medical error?

“When you think about it, when you’re in the hospital and there’s a medical error, that often means they’ll have to do an additional procedure to fix the error,” he said. “How does a patient know, how does the insurance company know that there has been an error, and yet they’re paying for it?”

About one-third of respondents indicated they suffered a serious financial consequence, and about 28 percent said a minor financial consequence.

“Iowans are really looking for two major things,” Lind said. “If an error occurs, tell me that it happened. And tell me what you’re going to do to make sure it doesn’t happen to anyone else. That’s the primary reasons that patients who have experienced medical errors report those errors, not only in Iowa but on a national basis. They just don’t want the error to happen again to someone else.

“The second thing that Iowans would really like to see is that the providers report errors — all errors — to a state agency so that we have a better understanding or repository of medical errors so that we can now attack the problem. You can’t attack something if you don’t know where the problem is.”