Des Moines Civil and Human Rights Commission has stepped up pursuit of discrimination cases

JOE GARDYASZ Aug 26, 2020 | 4:27 pm

9 min read time

2,057 wordsArts and Culture, Business Record Insider

When Joshua Barr was first offered the position of director of the Des Moines Civil Rights Commission in 2015, he initially turned it down because he didn’t want to be a “figurehead” for a city agency that was not going to admit there were any problems with race in Central Iowa.

City leaders invited him to return to Des Moines to speak further with civil rights leaders locally, and he was encouraged to take the job and moved from Columbia, S.C., where he was staff counsel with the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission.

Barr believes that community engagement is a key way that he and his agency can help effect systemic changes. The commission’s most recent annual report lists a number of initiatives that the city has undertaken, among them the “Bridging the Gap” forums spearheaded by Mayor Frank Cownie.

The Des Moines commission is one of 25 local human and civil rights agencies operated by Iowa municipalities. Additionally, the Iowa Civil Rights Commission enforces the Iowa Civil Rights Act of 1965 for areas not covered or ceded by local commissions.

While the commission has ramped up the number of total cases and with that the number of “probable cause” cases related to racial discrimination complaints under Barr’s leadership, he’s focused on addressing the underlying patterns that the cases represent.

“We will never solve the issues that have been going on for centuries by dealing with this case by case,” Barr said. “And I say that as a former civil rights attorney who left the litigation side because I was doing the same kinds of cases with just different names, and I didn’t want to be a hamster on a wheel — I wanted to resolve these issues.”

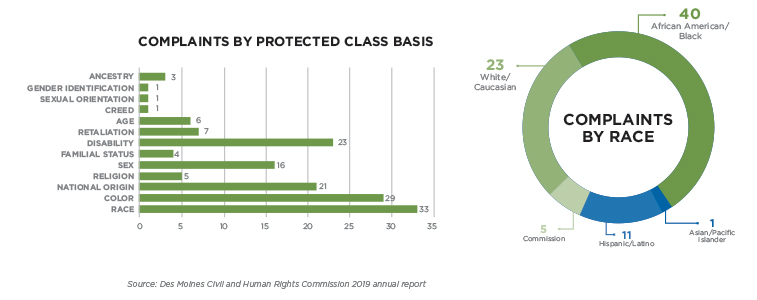

Approximately half of the complaints handled by the commission fall under the category of alleged housing discrimination, while the other half involve possible employment discrimination.

The majority of cases investigated have in the past typically resulted in “no probable cause,” meaning there wasn’t enough information to make a decision, or the evidence determined that the person was not discriminated against.

The investigation process begins by writing a charge of discrimination that outlines the allegations that tie the actions to discriminatory actions, with input from the complainant about the facts and any evidence or witnesses. The written complaint is then sent to the respondent, who gets an opportunity to respond. In that reply, they may provide evidence demonstrating why their action was not discriminatory. If the respondent doesn’t provide evidence, the commission has the power to subpoena the respondent.

A member of the civil rights department then conducts a rebuttal review interview with the complainant, in which the complainant hears the respondent’s side of the story and any evidence submitted by the respondent. The complainant then has the opportunity to provide any additional witnesses and evidence that he or she has.

“We then review all the evidence that we have in front of us and make a determination whether or not there’s probable cause that this person was discriminated against,” Barr said. “Many times we may actually conciliate a case before it ever comes to a decision.”

A conciliation, Barr explained, “is where we get the parties to come to an agreement, whether it is a monetary payment agreement, an agreement that revokes a write-up, or giving back a benefit. If a person was terminated, it’s typically a monetary benefit. In a conciliation we consider the case closed, and we don’t make a decision based on the evidence that was gathered during the course of the case.”

By focusing on more diligently investigating cases, the number of probable-cause cases filed with the city have risen about 170% during his nearly five-year tenure, Barr estimated. Additionally, for the first time in his tenure, in the last fiscal year civil rights complaints by African Americans made up the majority of cases filed with the Des Moines commission, he said.

Of 45 cases closed out in fiscal 2019, 18 were probable cause determinations, followed by 13 closed through conciliation. Ten other cases were closed out for no probable cause or dismissed for various reasons and four were waived to the Iowa Civil Rights Commission, according to the commission’s most recent annual report.

“The increase in probable cause cases really depends on the standards of the agency,” Barr said. “I am pretty diligent about making sure that we actually conduct proper investigations and ask the right questions to make sure the dots are connected.”

The process

The commission’s jurisdiction is “protected-class” discrimination as defined by Chapter 216 of the Iowa Code, which outlines 14 categories, among them race, color, creed, sexual orientation and age. If the complaint is identified as protected-class discrimination, the commission files a charge of discrimination that lists the allegations that tie it to a discriminatory act.

“The question to determine is why they’re filing an allegation — why do they believe that this is related to race, sex, color, creed or national origin, etc.?” Barr said. “Part of this work is getting the full story, and really understanding it, because most parties only see things from their perspective. So our job is to get the complete story.”

“One of the things that we’ve done over the course of the past few years is really trying to explain to people that when we do our work, it’s all based on evidence,” he said. “So if you’re saying [someone is] racist, and you have no evidence, no emails or voice recordings, [you won’t have a case].” Overall, the department has been doing a better job of instructing complainants that they need to come forward with information that demonstrates that there is some sort of disparate treatment, Barr said.

In investigating employment discrimination allegations, the company’s side of the story can’t be taken as gospel, Barr said. But neither should the word of the employee.

“My belief is that the quickest way to get to the truth is to believe that everybody’s lying,” he said with a laugh. “So we scrutinize both sides and see whose story holds up in the end.”

Sorting out alleged employment discrimination can be particularly difficult.

“To be clear, there is a difference between organizational discrimination and bigots and harrasers, and bad managers and failure to communicate,” Barr said. “There is a line that gets blurred, and [it can be difficult to determine] whether that’s illegal discrimination or it’s just a bad manager.”

The best organizations are the ones that proactively take steps to address social safety at work, he said. In practical terms, it means “that in my social settings, I am safe and secure to be myself and that I am not judged by the characteristics that I cannot control in the workplace,” Barr said.

“We’re all different; there will always be human conflict,” he said. “But I’m hoping that we can get past human conflict on the basis of color of skin and sexual orientation and gender identification and sex and get down to how do we mediate this difference between two human beings who think differently? That’s the point I hope that we get to.”

‘Grossly underfunded’

On a per capita basis, the city of Des Moines budgets far less than other, smaller Iowa cities that have their own civil rights commissions, Barr contends.

“Most agencies like ours nationwide have been historically underfunded,” Barr said. “You’ve got to give them the tools to win the war. The No. 1 thing is funding.”

Barr wrote in the commission’s 2019 annual report: “Presently, we are grossly underfunded as we only invest $2.24 per resident into the department; whereas, other smaller cities in Iowa are investing close to or over $4 per resident into their respective civil and human rights department. As the demand for our services grows louder, we must meet the call.”

According to city budget documents, the Civil and Human Rights Department’s amended budget for expenditures for fiscal 2020 was $620,498. For the current fiscal year 2021 that began on July 1, the department was funded at $755,836 — a 22% increase from fiscal 2020. According to city officials, the increase represented the addition of a compliance manager position, with salary and benefits totaling $136,675.

Kameron Middlebrooks, chairman of the Des Moines Civil Rights Commission, told the Des Moines City Council in June that the commission needs to be more proactive to fight human rights injustices. Increased funding would enable the city’s Civil and Human Rights Department to field three divisions: equal opportunity enforcement, equity and community relations.

Middlebrooks, who also serves as president of the NAACP’s Des Moines branch, said that “investing in the Civil and Human Rights Commission can go a long way towards making sure that we are collectively stronger as a community as we recover past these crises,” the Des Moines Register reported.

Malcolm Hankins, who joined the city staff in November as Des Moines’ assistant city manager, said the city manager’s office is committed to putting more resources into inclusion and diversity efforts.

“I think there is an awareness that we need to do more work in this area,” Hankins said. “Because of the work we’ve done in Bridging the Gap, there is a likelihood that we’ll identify the need for additional resources in that area.”

Bridging the Gap is a city-led community initiative launched in 2018 with a mission “to address community issues, improve community-government relations and remove systemic barriers, so that all Des Moines residents have the opportunity to achieve their full potential.”

Hankins said he is enthusiastic about each of the recommendations that were laid out by the commission in a June update to the City Council. Among those recommendations are housing incentives to encourage more city employees to live within the city limits; mandatory cultural competency training annually for all city staff, boards, commissions and elected officials; and creating a workforce equity plan to ensure the city government and boards are representative of the community’s demographics.

“I think they all have importance,” he said. “I think they all will have an impact as we work through them.”

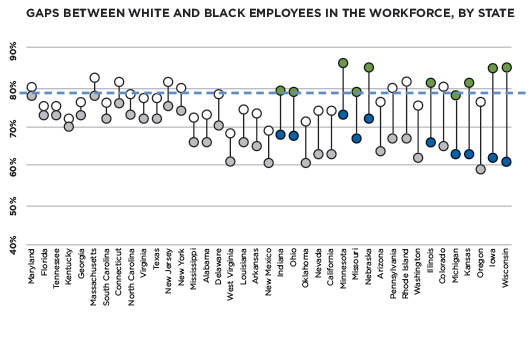

The dots plot the metrics for Black and white employees in the workforce by state, and the line between the dots indicates the gap. The states are ranked from best to worst (left to right), by the ratio of white to Black values. The symbols for the 12 Midwestern states are highlighted by coloring the dot for the white value green. The dotted blue line is the national prime-age employee percentage of population rate (all races, all states), 78.9%. Source: American Community Survey, 2017

Study: Midwest states among the worst for racial disparities

A study released in October 2019 by the Iowa Policy Project with other Midwestern research organizations, “Race in the Heartland,” took a comprehensive look at racial disparity and how many Midwest states can simultaneously rank as being among the best places to live but often the worst places to live for African Americans.

The study highlighted significant historically driven and systemically sustained gaps that exist for Blacks in education, wages, income, incarceration rates and other factors that profoundly affect their ability to attain equality.

One indication of implicit bias against Blacks measured in the study is the difference between the proportions of Black and white people who are in the workforce.

Out of all the states, Iowa has the second-highest gap, with the percentage of prime-age white individuals in the workforce being in the mid-80s, compared with the percentage of Blacks in the workforce in the low 60s. Four other Midwest states — Wisconsin, Kansas, Michigan and Illinois — were also with Iowa among the bottom six states with the highest gaps.

Implicit bias and its effects can make enforcement efforts problematic, the authors wrote.

“While overt and actionable acts of employer bias are not uncommon, workplace discrimination stems largely from forms of implicit bias deeply embedded in workplace culture, practices and decision-making. As a result, antidiscrimination law — even robustly enforced — offers meager remedies or disincentives.”

READ MORE: Class-action lawsuit: Is Wellmark implicitly biased against its Black employees?