Fitting the form

Des Moines plans to take a new approach to zoning

KENT DARR May 6, 2016 | 11:00 am

16 min read time

3,736 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Real Estate and DevelopmentIn March, the Business Record hosted a panel discussion about trends and issues in land development in Greater Des Moines as part of a series of four videotaped discussions on the office, retail, industrial and land subsections of real estate. We wrote stories about each discussion for our Annual Real Estate Magazine, which was inserted in the April 29 issue of the Business Record.

The conversation on land and development started with a question about efforts in the city of Des Moines to alter its zoning and speed up approval processes for certain projects in specific areas, or nodes, in the city. The process to change the city’s zoning ordinance could take another 18 months. It is generating a lot of interest as illustrated by the conversation that resulted from the first question of our discussion.

We felt this portion of the discussion was so robust, that we decided to cut this section on zoning from the story in the Annual Real Estate Magazine that touches a variety of topics, and instead publish it as a separate zoning-specific story in the Business Record.

Members of the panel were: Jake Christensen, president of Christensen Development; Phil Delafield, community development director for the city of Des Moines; Chris Della Vedova, principal with Confluence Architects; and Joe Pietruszynski, director of land development for Hubbell Realty Co.

Real Estate Roundtables

The Business Record videotaped four discussions on different segments of the real estate and development market. Watch all four at businessrecord.com/AREM.

The Annual Real Estate Magazine

The Annual Real Estate Magazine contains stories on four segments of the real estate market, 11 trends to watch in 2016 and beyond, market facts and sale listings for each segment and broker profiles. Interested in purchasing the magazine? Go to www.businessrecord.com/AREM.

Phil, tell us about the city’s effort to help direct development along the key nodes in Des Moines?

Delafield: The projection is that our population will be growing by 40 percent by 2040. Where will that 40 percent live? What will that population look like? Just this year, we have hit our highest-ever population here in the city. It was a period of decline from the 1970s through to the ‘90s. We’ve turned that around, and now we are seeing positive population growth. A lot of that is occurring in the downtown area, but it’s also occurring out in the neighborhoods.

Our existing development patterns have largely been reactionary. The development community comes to us with an idea, and then we sort of say, does it fit with what the community character plan currently says, and if not, will you modify the plan. That sort of process, that reactionary process, leads to a lot of angst among the developers and the neighborhoods because there is no predictability whatsoever. Every project is individually negotiated. This process, if we’re successful, will envision a series of detailed areas, plans, form-based documents that will suggest that if you go to a certain form, a certain building model in certain areas of the community, we will then in turn pave the way for that development to occur.

We trade off time. We would give you an administrative process to run through rather than a series of public meetings. What it amounts to is making the decisions in advance based on the types of development patterns we hope to see and making that easier for the development community so they have the predictability in those areas. It is also a trade-off for the neighborhoods, who are always concerned about what products may occur in their neighborhood and whether or not it’s objectionable in some fashion. Getting the form of the development correct up front then becomes key. Can we have that conversation in advance of a specific project so that we make those decisions under informed circumstances? That’s the most exciting piece that I see for tomorrow. We’ll do the comprehensive plan with the City Council.

Right on the heels then, there is an orientation chapter. Right on the heels of that, there will be rewriting. We’ll take another 18 months. At the end of it all, we’ll have a new set of evolved regulations that will guide the growth to 2040 or thereabout.

KEY POINT: A development guide

Instead of reacting to each individual project to determine if it fits what the city wants, Des Moines is creating a plan that will identify what can and should go in certain areas, ultimately helping guide developers and fast-tracking certain projects.

Does all that work help or hinder or inhibit or intimidate developers?

Christensen: I will say that all of the cities in (Greater) Des Moines have been more receptive in the last, definitely five years, to different ideas, to different thoughts coming forward. In my mind, the form-based code and that approach is just the next step to make that an easier process. One question I would ask is, do you think we’ve actually moved past the auto century (that accommodated people in vehicles, as opposed to walkers and users of mass transit)? Part of me still can’t believe that with everything we’re dealing with, we’ve still got to address the matter. I’d like to think we are past it, but I don’t know that we are.

Delafield: I think we’re in a transitional period. Automobiles will remain important to the community. But we want to provide the opportunity for the people living in Des Moines or the metropolitan area, if they so chose, to use other modes of transportation. That helps our low-income folks enormously. If they can rely on mass transit, they gain marketability. Those are all important concepts. Also, locating the housing near the work centers so that it isn’t necessary to drive all the way across town twice a day for work. Those things all start to align when you take a comprehensive approach to this development pattern. I would like to say in 2040, we will be much farther away from the idea that you have to have a car than we are today. Remember, it’s a vision and it’s a process to get there. It’s not going to happen overnight. We can’t redevelop the whole community overnight to be a walkable community. We can take steps now that will make sure that we don’t eliminate that option for the future.

Christensen: Downtown has had explosive growth over the last 10 years. In the early years, there really wasn’t much of a downtown neighborhood association to contend with if you had a project that was questionable. The stronger the downtown becomes, the stronger the community association becomes, which is a good thing. I think having a group plan for all the projects going forward will be beneficial on both sides. It will be more predictable.

Pietruszynski: It’s an interesting perspective for form-based zoning and where it applies in the city of Des Moines. In Des Moines, you have two different dynamics. (One dynamic is) very powerful and very vibrant, with a lot of capital, a lot of investment occurring and a lot of opportunity for diverse housing and unique ideas. The value is there. The demand is there to do some great things. This approach that Des Moines is taking will help. The other areas of Des Moines are more sensitive, but there are also opportunities where there’s infill area spread throughout Des Moines that allows for diverse housing. That could allow for people to stay in their neighborhoods and have new housing opportunities. I’m not sure how the form-based zoning would play with that segment of the market versus the downtown.

I do know that building in Des Moines in those infill areas is always a challenge to make sure that it is consistent with the surrounding neighborhood, that densities match, that housing patterns match. That is more challenging because the margins, the expectations in those areas because of all the complications are very low and risks are high. I don’t know how form-based zoning is going to play into that type of development in the metropolitan area. I can definitely see it in the downtown.

Delafield: I can see it working very well in the neighborhood. If you give a look at the history of how we developed, you see we had this sort of transferring development pattern. We had the railroads enter the urban lines, and all sorts of trolleys and so forth that laid down the underlying development we’re dealing with today. Where you now see strong neighborhoods like Beaverdale or Highland Park … those used to be the ends of transit lines. If you extrapolate from that a little bit, there was a market there because that was the end of the line. If you lay down your nodes and corners (in a way) that fashions and respects transit, respects those development patterns, you can then start to see the opportunities that these nodes and the resulting connecting corridors between these nodes start to offer.

While you might have a very strong downtown, that is obviously something we want to continue with. But on a smaller scale, if you take a regional node like Merle Hay Mall or the Southridge area, you already have transit corridors that are there. You have highways that are there. You have the development patterns that support the movement of people, so you can start to consolidate and densify in those neighborhood nodes. Maybe in the regional nodes like Southridge Mall or Merle Hay, you have a little bit higher density where you can develop.

You can then start to say in the smaller neighborhood nodes, there are other options. It could be handled with densification of a small area. I’m not talking a high-rise in Beaverdale, but a three-story form of development that has walkability as a component where it embraces the street rather than a parking lot that embraces the street. Those sorts of options are the trade-offs that you’ll begin to talk about with a form-based code. We give you the ability to do these sorts of developments at a higher density. Maybe something low to medium. Medium to high density in the neighborhoods. As you transition out, you go from higher density, to lower density, to neighborhood density. You have this sort of whole scope of or whole palette of development patterns that you can start to use in these areas.

You have to be respectful to what the existing area’s character already offers. I would expect to see something that respects the Beaverdale form: the bricks and the pitches in the roofs and those sort of things. We have other areas of the community that are Craftsman and other areas that are modern. You start to have a palette. Maybe it’s even a category that says in these types of neighborhoods, these are the types of form. You do these sorts of things, then the trade-off is that by right, you get it fast. You get it predictable. I think it can work. I think it’s a remarkable concept. It’s the security that the neighborhood needs to know that the character that they value is not going to be just thrown away. It respects the future, but it also respects the past. I think it’s a very big opportunity.

Christensen: I think that’s true as long as, and where I think Joe was going was, that the council will then have to use that guiding document and then potentially overrule the minority of people who are just against change. I always say that when you’re going to a neighborhood where people care enough to stand up and take issue, that’s a good sign usually because there’s some strength in the neighborhood, but I also think they need leadership from the city staff or the council to enforce whatever’s been put forth.

Pietruszynski: In city infill areas, especially where the densities are lower, to go after the higher density to make the project economically feasible, that does become a bigger challenge as you move away from a metropolitan area. That’s going to remain a challenge in the infill area. What solutions can we put in place that will help promote the investment and bring comfort to the neighborhood at the same time?

Delafield: Those are the sorts of things that we expect to struggle with, and we’ll deal with that as we struggle. The city has all sorts of tools and schools of thought, and we have applied them without any sort of overarching guidance or response. We have property that we own. We have right of way. All of which can be used collectively. We’ve already made the investment in the areas. We have the infrastructure in place to support traditional density. We already have a street network, we have a sewer network, we have those things that are in place. They are advantages.

If we use the resources that we have strategically so we get the best return on the city’s investment that’s already been made, we can go forward with the resources that we have. We can incentivize when we want and where we want in a logical way. Rather than having one size fits all and not use any sort of structure at all.

KEY POINT: Neighborhood associations

When neighborhood groups take a stand, it is a sign that they are vested in their area. That’s a good thing for the health and vitality of a city. As one panelist said, “The stronger the downtown becomes, the stronger the community association becomes, which is a good thing.” That applies to all neighborhoods.

Are these logical development corridors?

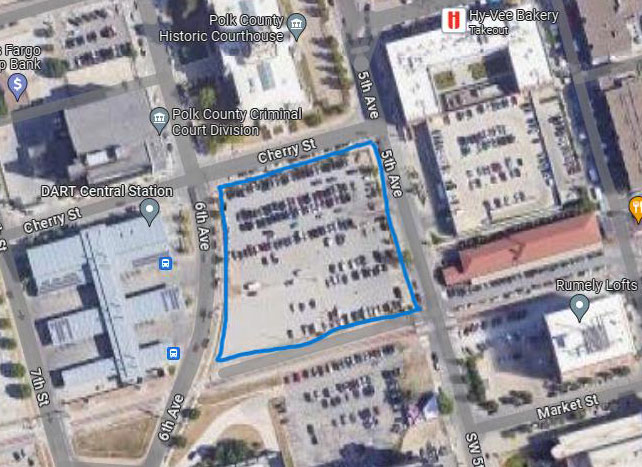

Delafield: I would think so. You would start to see that we’re talking about along Southeast 14th Street, along Southwest Ninth. We’re talking about Beaver and Merle Hay and Douglas and all the main corridors that everybody already travels, and we’re aligning that with what they were saying with the transit nodes. Where does transit already exist? What services are already there? What sort of connectivity do we already have within those groups, and can we make that alignment work?

KEY POINT: Respect the ‘palette’

Working from downtown out, it is important to respect historical designs, such as the Beaverdale brick, possibly by helping new developments that fit an existing form. There are bound to be trade-offs, such as accepting a certain density in a project that also promotes walkability.

Are any of you out buying property in any of these areas? Do you have any clients who have property in these areas? Chris?

Della Vedova: I can’t say.

Delafield: It’s pretty early in the game. We are in a transitional period. Finding our way through transitional times is going to be one of the challenges. We have had our old path of order. There will be the desire to continue that old path of order. As we move forward, hopefully we can transition to this new model. Hopefully we can transition to this new model that says we are using the best information that we have available to guide the decisions and guide the application of the limited resources that we have.

Christensen: That’s not to say that if somebody comes in with a development, that’s not going to move forward.

Delafield: Certainly it’s going to be looked at, and certainly it’s the property owner’s right to develop their property. That doesn’t mean that it would be necessarily eligible for assistance. It would probably be market grade. If it does happen, let’s say we’re looking at one of the annexation areas. We don’t have streets out there, we don’t have fire stations, we don’t have police stations. All of those connections need to be made. If we have an annexation area and somebody says, we want to do a development area out here, what will the cost, the true cost, to the city be? Will we have to build a fire station? Will we have to build a roadway? What size of a roadway does it need to be? Is the sewer there? Is the water there?

Those types of questions should be asked. Then the decision can be made. Is the investment that is being asked to be put into this, does it have the return on that investment for the community? In many ways, it’s kind of asking the question, ‘Is it right for the development now?’ Should we be rolling from the inside out or from the outside in? The pattern that we’ve had so far has been hopscotch. We go here, we go there. There’s no coordinated effort. Public Works puts in a sewer over here, Public Works puts in a sewer over there and when the development occurs we have half a road until the rest of the property owners in the neighborhood start to develop it. That’s a pretty haphazard way of development. Guided growth seems more logical to me.

Pietruszynski: I think that’s one of the bigger challenges, especially following the recession, in terms of economic growth. Not only in Des Moines but even West Des Moines, Waukee, Urbandale. Where is the infrastructure? What kind of public investment was put in place to promote growth? We are definitely seeing the cost of construction escalate. A lot of people are thinking that those cost escalations are socially a significant point in development. They attest to the fact that that’s not the case. You’re seeing more margin erosion with the inflation of cost because the development community is not having to absorb all the infrastructure expenses to extend those facilities to the developments.

If you’re downtown, then you’re adding to costs that are already higher than what you’d run into in a greenfield development, correct?

Delafield: Perhaps. The infrastructure is there. The investment has been made in the streets, the sewer and the land. Yes, you may see some clearing costs. Yes, you may have some environmental costs, and I’m not trying to minimize those. Those are significant costs. The infrastructure is already there. We have lots of redevelopment opportunity. We have miles of underperforming commercial space in this community. Along Southeast 14th, we don’t have enough rooftops to support the commercial that we have there now. An orderly growth pattern would suggest that maybe we don’t need as much commercial space along Southeast 14th. Maybe some other model that brings in more rooftops so the commercial can follow. The commercial will follow the rooftops. We’ve seen it downtown.

Christensen: One of the big challenges is the development costs downtown. The idea that they’re just different. You may have put in a road and water and utilities. In my city, we have roads, but we’re dealing with 100 years of buried rubble and whatever environmental situation has occurred. I think in most cases, the cost increases are in large part due to the lack of labor. That might be a byproduct of the recession, but it might also be a byproduct of our slow population growth in Iowa as a whole and our extremely low unemployment rate. We just did not have a way to break that preconception, and it’s having a real impact on cost.

Is there a type of a product that’s on the horizon that would be a real eye-catcher?

Delafield: That’s the interesting idea, right? That’s where the big thinkers make all their headlines. I kind of think the organic movement is starting to get some legs under it. The box. The downtown box; we have plenty of those glass boxes. That was the big thing for a while. The workplace is evolving, and how people want to work is evolving. Right now, it’s cool to have a little cool place that has the sleeping nooks and the collaborative spaces and all sorts of things. What the next big thing is, I don’t know. I see it’s the organic look that’s starting to grow a little bit. I start to wonder, how is that going to mesh with the new technology? They’re printing buildings now; 3-D buildings with 3-D printers. How’s that going to change architecture? Those are the sorts of things that intrigue me. Am I suggesting that they are going to happen tomorrow? No. But I look at what happened with the Krause Gateway Center and how that approached the environment around it, and I see the logical progression. It’s just exciting stuff.

KEY POINT: An iconic office building

Make no mistake, the Krause Gateway Center is going to be a game changer, attracting people to Des Moines for no other reason that they want to take a look at a piece of architecture that will stand out from anything else in the city.

Did that design catch everyone off guard a little bit? Did you expect that? It’s pretty unique.

Delafield: I appreciated the process that they went through to get that. They went through the visioning process. They evaluated visual preferences and workflow preferences. That was unique in the way that people have approached a development. At least in my experience. It happens on a smaller scale or it happens on the neighborhood level or it’s a process that we use in the corridor planning for example, in neighborhood planning. As a building planning exercise, it’s less common, and I’ve found it really refreshing.

Christensen: I don’t think most people appreciate the impact that that building is going to have regardless of the people and the jobs and all that. I think that’s going to be so iconic that people will come to Des Moines just to see it.

Delafield: What’s especially nice is that it adds to the fact that you already have a great history of architecture in this community.

Della Vedova: I think you go out and search out an architect, you’re going to get an iconic building. Nobody should have been surprised that it’s a unique building. We’ve gone through a tremendous process in our estimation of being involved, and it’s been a great process to be involved in.

Pietruszynski: I don’t think it creates surprises. I think it creates excitement for the companies that are investing in downtown. When you see someone make that kind of their own investment, it just promotes you to do more. Success promotes success. I think for us, it just generates that excitement and keeps us moving forward to take more risk and to develop the town in a more positive way.