Food Safety

ISU seeks to be a leader in packaging research

PERRY BEEMAN Oct 30, 2015 | 11:00 am

4 min read time

938 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Innovation and EntrepreneurshipWhen someone wonders if a nonstick frying pan coating sends dangerous chemicals into food during cooking, or a manufacturer debates whether a package will hold up on the shelf, or downtown workers can’t decide if warming up leftovers in a plastic container is a health risk, Keith Vorst wants them to go to Iowa State University for answers.

In fact, Vorst wants the whole country to see ISU as the center of the packaging analysis universe. Short of that, at least the center of Midwest research in the field — and, yes, he knows that Michigan State University has a strong program.

Vorst is trying to establish a big center at ISU, where some professors are eight years into studying all aspects of packaging, safety, shelf life and costs.

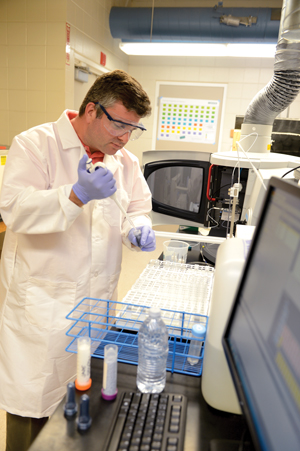

Already, Vorst has succeeded in a top goal he had when he left California Polytechnic State University to join ISU a year ago: the establishment of the ISU Food Packaging Laboratory. He came to ISU after five years at Cal Poly, in part because of ISU’s heavier research focus and better resources.

“I am trying to pull all ISU resources together to start developing packaging in general, design to function to costs,” said Vorst, an associate professor in food science and human nutrition at ISU. “If it touches a package, we want to be involved.”

Vorst has more than a professional interest in the work. His 8-year-old son is on the autism spectrum. “Is it plastics?” Vorst, the scientist, has asked himself repeatedly.

Cancer has invaded his family too. “It’s human nature to ask, where is this coming from?” Vorst said.

But we have to be realistic as well, he added. Paper bags give up contamination. We often breathe benzene at gas stations. Most of us are OK.

“We have to have some common sense with this too,” Vorst said.

The idea is to examine everything from chemical leaching during cooking to the cost of the package and whether it will survive shipping and stocking.

“They have been doing this for years,” Vorst said of ISU’s professors. “They just haven’t put a label on it. We have lots of untapped resources.”

A new curriculum is in the works, and ISU is holding seminars on the topic.

The program has three graduate students, an administrator and a doctoral research associate. A couple of Cal Poly professors are helping part time from their California offices. Ultimately, Vorst would like a staff of 12 at an ISU center supported by grants and its own income.

In a world of water bottles, plastic bags and significant manufacturing, this is a big deal. Chains such as Trader Joe’s and Costco have become big sources of recycled plastic containers — for produce, for example. Many fear that plastic microwave trays and disposable water bottles are not safe.

Vorst realizes that Michigan State University, for one, is big on these issues. He hopes to build something even bigger, establishing a center seen as the top authority in the Midwest, at least.

A big part is keeping consumers safe, and telling manufacturers whether their products are safe.

“We are heavily involved in the food safety part of it,” Vorst said. “We talk to parents who are afraid of anything that touches food. When they hear we are recycling food packaging, they ask, ‘How is that safe?’ ”

Some of the materials are flaked and screened, and put back to use. “There is resistance to that,” Vorst said. “Is that really safe? We do half our work on food safety.”

Sometimes companies are redesigning packaging. Sometimes they wonder about heating the product in a microwave oven. “We did a big study,” he said. “What happens if you microwave the package? What happens if it sits in a truck in the Arizona sun? What happens if you dump dressing into a plastic container? Is that an issue?”

“The results are really promising,” Vorst said. “In water bottles, we haven’t seen a big safety concern. There is still a concern of heavy metals and inorganic and organic contamination. They are there, but they are not getting into food. But what about the degrading in landfills?”

Many of the results in the field are touchy subjects, so peer review is important before the full results are released, he added.

Which brings up a related point: Vorst and his colleagues have a system to ensure that the funders don’t influence results.

“That gets tricky,” Vorst said. “Companies may come in with their own agenda.”

A university conflict-of-interests committee helps ensure objectivity. Each study has a time limit and blind peer review. The laboratory works with regulators, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery to ensure the work meets quality controls.

“I don’t mind doing controversial research, but I can’t be influenced by the funder,” Vorst said. “We are going to report what we find.”

Brenda Martin, based in Fort Dodge, is a former employee of Nestle who now works in account management for ISU’s Center for Industrial Research and Service, helping spread the word on food packaging.

“We can test food packaging and pharmaceutical products to see if the shelf life is what it should be,” she said.

Safety isn’t the only issue. So is the bottom line.

“Packaging is one of the biggest expenses, so they need to know how they are performing,” Martin said.

The companies supporting the center’s budget of “several hundred thousand dollars” include makers of pasta, animal feed, vaccines and ice cream, Martin said.

“As everybody becomes more cost-conscious and health-conscious, this research becomes more important,” she added.