Housing Roundtable Q&A – 2020 Annual Real Estate Magazine

KATHY A. BOLTEN Apr 20, 2020 | 4:30 am

18 min read time

4,381 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Real Estate and DevelopmentNearly a year ago, Capital Crossroads, the Polk County Housing Trust Fund and several Des Moines-area cities released a study predicting that more than 150,000 new jobs would be added to the region during the next two decades, sparking a need for affordable housing located near large employment centers.

The new jobs are expected to generate 84,000 new households, two-thirds of which will be in Polk County, the report said.

More than two-thirds of the new households will have annual incomes of less than $75,0000, the study said. That means more than half of the new owner-occupied homes will need to be priced below $175,000 and three-fourths of the new rental units will need to charge monthly rents of less than $1,250, according to the yearlong study.

The need exists now, the report said.

The region’s two fastest-growing job centers are in Ankeny and West Des Moines. But while Ankeny is generating housing at a pace equal to job creation, new housing is not affordable to low-wage workers, the report said. West Des Moines is adding new jobs at a rate that outpaces new housing starts. West Des Moines “offers less opportunity than other jobs centers to live and work in the same city,” according to the report.

City officials, businesses leaders, philanthropists, homebuilders, residents and others will all have to work together to develop a plan to provide the needed housing, said a panel of residential sector experts.

“How do we come together as a region and be thoughtful about our regional housing market?” asked Kris Saddoris, vice president of multifamily development for Hubbell Realty Co. The conversation, though, needs to begin before a developer brings a project before a city council, she said.

Eric Burmeister, executive director of the Polk County Housing Trust, agreed. “We have to be having these conversations now and very broadly instead of the time that the developer is standing at the podium arguing with the council,” he said.

Read the discussion, which occurred during a recent Business Record Newsroom 515 event:

Q. What are the main issues facing housing and residential development in 2020?

Kris Saddoris: First, let’s change the talk to say attainable housing because affordable tends to mean “those people.” I’m going to argue that all of us need attainable housing. I think that’s, to me, the biggest thing that’s facing our industry is understanding what that means, what that means for our community, what that means for anybody that’s a manager, corporate owner, business owner. You should understand what kind of attainable housing you have for your employees, and so what does that mean in our community? What do we need? Because we know the biggest challenge facing Des Moines is that we need bodies. Two percent unemployment is a bad thing.

Ben Champ: I would agree with Kris that the conversation is more than just affordable housing; the conversation we have every day is about housing for all, and that includes affordable housing, but that’s about choice for everybody in every piece of the market. … There are available houses in all pieces of the market, but that doesn’t mean that they are the right house for everybody, and that’s different than the affordable conversation at the other end of the spectrum.

Eric Burmeister: I think that there are really two big issues that are facing us right now, particularly in light of the workforce housing report. As I told my board, there are two V words: value and velocity. And so the first thing that we know is that the population is going to grow very quickly, and so the velocity of building in this region is going to have to be at a rate that is a lot higher than it’s been in the past if we’re going to meet that demand. The second is value, which means we’re going to have to be building the right product at the right price, and so we’re going to have to know what those needs are for this population that’s coming in.

Frank Levy: I’m more of a niche guy, and so I’ll add to the conversation that there’s three or four major neighborhood transformations that any developers or development services people want to figure out. One is this move of [Des Moines University] that is going to radically transform the Grand and Ingersoll avenue corridors. Our office is by Valley West Mall. Valley West Mall is struggling. There’s a similar thing at Merle Hay Mall. And finally, you’ve just created a new neighborhood [Hubbell’s Gray’s Station] that’s going to radically alter the center of gravity in downtown. Those of us who are developing have to figure out what that means for our projects.

Eric Webster: From my perspective, from a residential real estate side of things, I see an ever-widening gap between something for a first-time homebuyer that is in the $220,000 and below range. There’s a lot more inventory in the $325,000 and above than there is the other way. New construction is focused on the higher end of things. … I think that the $100,000 gap between a resale home average price and a new construction home is a big issue that faces our community today.

Q. Several communities here and across the country are embarking on redeveloping neighborhoods. In some communities we’re seeing the emergence of pocket neighborhoods, smaller houses built on smaller lots. Let’s talk a little bit about how you go about redeveloping a neighborhood and sort of what that might look like today.

Lynch: I think within the city of Des Moines a lot of what we’re trying to do is reinvent a neighborhood that’s already there. We don’t have a lot of land that is vacant that we’re trying to develop with new product. … We’re starting with what’s there now and [looking at] how do we upgrade and update those existing homes in a way that makes them continue to be attractive in the marketplace. … I think there are some places where we do have opportunities to maybe take down, or reinvent, a particular block or a particular site. When we can do that, the more that we can start to bring in some more diverse housing types.

Q. Why is it important to redevelop a neighborhood?

Champ: From a municipal perspective, a taxpayer perspective that we’ve got infrastructure that’s already there. We’re going to be maintaining that forever regardless. If we can add density, if we can add tax base to that location, everybody wins and we’re going to take care of it forever anyway.

Q. What are some of the challenges to redevelopment in struggling or deteriorating neighborhoods?

Saddoris: We’ll talk about this a lot, but the biggest challenge is costs are going [up]. Construction costs last year were 6% [higher than the previous year] and if you just take that … multiplied over the last few years. Salaries [aren’t going up 6%] every year. … We need housing at that $220,000 range. Well, we can barely build it. … The housing study talks that most [new workers] are going to earn below $75,000 a year. Do the math. It doesn’t work.

Webster: Builders are leaving their pricing the same, but taking the hit on the 6% increase, that’s what I’m seeing in the numbers.

Lynch: Part of the reason why it’s difficult to redevelop in some of the center city neighborhoods, the urban neighborhoods, is because consumers are preferring to buy where they can get new construction out in other parts of the community. There’s less demand for those inner-city neighborhoods over time and prices tend to fall. Even renovating a structure that’s already there, the cost is higher than the resale value can support. We have this funding gap that we’re trying to overcome. A private individual often is going to either choose to not make that investment, in which case conditions then continue to decline, but it starts to spread across the neighborhood. Then it becomes just a much more difficult lift to get the whole neighborhood back to where it needs to be to stay in a healthy condition and functioning in a market way.

How are we going to prepare to offer workforce housing, and what are the ramifications if we don’t prepare?

Levy: Betting on that trend, we’ve just acquired some older product. We’ve acquired two apartment complexes on Grand Avenue, the Imperial and the Grand Prix. They were built in 1966 and 1968, and we’re going to renovate them and try and reposition them at a cost of about $15,000 per apartment and … hopefully meet some of the need you’re talking about because it won’t be a new construction cost. We did pay dearly for the apartment complexes. We’re counting on job growth, population growth, income growth being a good fit for older but upgraded apartments right now.

Burmeister: I think that the issue that we’re going to face — this incredible population growth is just simply an increase in the cost of housing across the board, whatever type it is. … You know there’s going to have to be price increases and rent increases are built in somewhere there, and again, the wages that are being paid are not going to support those kinds of increases. What happens in most markets — and I will argue that it’ll happen in Des Moines — is you’re going to start to see this constricted demand cause artificial price increases. …You’ll end up with a supply and demand problem.

Q. What does that affordable/attainable housing look like for somebody who doesn’t want to buy new but who is looking to buy their first home?

Webster: If you are an enterprising person and a little bit industrious and maybe slightly handy, you can invest in these properties and do a lot of good in this city. I have a number of Realtors that do invest in single-family rentals and you can build a nice portfolio, have good control and good renters, and in many cases I’m seeing where the renters actually retire the note for the investor and provide great equity. … I think that is a piece of the solution for sure.

Q. Whose shoulders does it fall on to make sure we have attainable/affordable workforce housing?

Champ: It takes everybody. It’s not the developer’s problem. It’s not the city’s problem. It’s everybody’s problem. … It’s going to take partnerships to figure it out; it’s going to take education to figure it out. In our community, we do talk about housing every day. We’re working on a housing strategy to try and figure that out a little bit. … It’s going to be change, and change is hard and people don’t always enjoy change, but change is coming regardless. … One of the things that we’re working on is just understanding density. … It can be small things like reducing lot widths or it can be having some mixed-use or multifamily.

We hear all the time, in our community, that “we want this or that, we want this amenity, we want this restaurant, or how come we don’t have that yet?” It takes density to get those things. … We’ve done a lot of education internally, and our elected officials have a really good understanding now of change that’s coming. … Do we form partnerships with developers to do that and then educate the rest of our public about why that’s necessary?

Burmeister: We’ve all worked hard to talk about how we reduce the price of housing. There’s another half of that equation — and this is where the conversation sometimes gets a little touchy — but the business community is going to have to recognize that there is not enough money either from the government or from the philanthropic sector to continue to fill the gap in the cost of housing and wages in this community. We’re not going to come anywhere close to addressing this problem until we start talking more about living wages.

Webster: On the residential side, one of the trends that we’re seeing is that these savvy millennial homebuyers are buying houses and renting rooms to their friends. That is one of the things that we’re seeing happening over and over again. I think it’s actually a pretty good trend because seeing young people buy a $220,000 to $250,000 house that might be a three- or four-bedroom and then renting out two of those rooms and paying their mortgage using their friends’ [money], in a good way.

Q. There are some communities that say, “Density is not for us” or “Housing of certain sizes is not for us.” So how do we break down some of those barriers and make that acceptable across the whole metro area?

Saddoris: I’ll argue it’s always education that’s honestly what’s going to motivate. I always encourage cities to have that conversation off-deal. It’s very difficult to have [conversations] on-deal because emotions are up, shields are up. We’re not really listening, we’re just waiting for you to stop talking so we can explain to you why you’re wrong, but it’s education. It starts with your leaders [who] have to understand. I’m going to argue that’s why the business community [has] to understand that we don’t pay our employees enough. I’ll tell you that you’ve chatted with one of “those people” today. I’m guaranteeing you either gave your most prized possession [your child] to one of “those people” and if your day care bill went up you’d be mad, or one of “those people” is the nice lady that trims your dog’s hair or gives you your coffee.

Where do “those people” live? You want restaurants, right? We want the restaurants, but we just don’t want “those people” living in the community. … If [“those people”] are good enough to be your day care provider, they’re probably good enough for your neighbor, right? And so it’s having those conversations. We all need to be educated. I hope you all go out and talk to whoever your friends are over beers. … Who are those people? They can be your neighbors.

Burmeister: I will tell you that if you ask most folks whether or not they think someone that works in a particular city [such as] … Pleasant Hill, do you think that person ought to be able to live in Pleasant Hill, or find a place that they could live in Pleasant Hill that they can afford?

Most folks, even some of the toughest [not in my backyard-ers] will say, “Well, yeah. If that person works here, they ought to be able to find a place to live.” So if you’re beginning to talk about … a broad housing policy in your community, you need to be looking first at your workforce and let’s figure out whether folks that work here can find places to live here if they want to.

[Doing that] makes the sales job easier, and if the council decides in its strategic planning session that that’s going to be the principle of whatever community it is, then when the project comes up and the neighbors start to come out — because they will — you can say, “Listen, we had this discussion a year and a half ago and this is our policy and this particular project fits it.” And I think it then gives some backstop to folks who have to face the firing squad, so to speak.

Saddoris: I’ll make one quick thing before I forget. I would encourage folks to understand the costs. What does those boxes cost? What does additional brick cost? What does a basement, a garage? Those costs are going up every day.

Q. Ben, have you had any experience with the residents not wanting some types of developments in their neighborhoods?

Champ: Yes, of course. A couple of things that we’ve done is to make it personal. We’ve used Eric and his team to come out and work with our staff, elected officials on a “know your neighbor campaign.” Who are these people? Who lives there? It’s your day care provider; it’s the person who just served you lunch. And, is it OK if they walk two miles back someplace else to go home every night, or should they be able to live [in Pleasant Hill]? By making it personal, putting a face to it and showing that “these people” are also teachers and law enforcement and firefighters who are all in those same pieces of the market.

Q. Some residents say that having an apartment project or houses on smaller lots reduces property values. How do you address that?

Lynch: The reality is that it doesn’t.

Champ: It’s perception, and perception is reality to the consumer, but it is not true. It’s the same as parks and other amenities. “I don’t want a park next door, but I want a park in my community. I don’t want a trail in front of me, but I want the trail in my community.”

Q. What are communities doing to provide more affordable or attainable housing?

Webster: One of the things that we’re seeing on the residential side is there’s a trend toward what we would call micro lots — smaller home sites for building. This is something that I think municipalities are starting to warm up to. They were not very open to it just in the recent years, however. I grew up in Highland Park, and I looked up the house that I grew up in and it had a 60-foot frontage. A 60-foot frontage gets you a little house; you have to drive by it in order to get to the detached garage in the back. We don’t build new construction that way today. We have these opulent frontages of 100-plus feet in order to build a single-family home. … Land prices are one of the key components in the gap between resale and new construction because of the raw land.

Anytime that we can go to a smaller-frontage home site, you’re going to be able to hit that demographic that needs [more affordably-priced houses]. … There’s some education that I think needs to happen along those lines to allow a little bit smaller home site.

Q. Let’s talk about multifamily specifically. What are the occupancy rates of multifamily, particularly the ones that have come online in the past year or so?

Saddoris: For years and years [Hubbell] didn’t [build any multifamily] because it didn’t make sense. We came out of the recession and we’ve all had an explosion. We in the Des Moines market have brought on unprecedented levels [of multifamily construction]. … Just in the third quarter [of 2019], we delivered about 1,100 units; fourth quarter we delivered about another 700 units. We have some vacancy now because we have the last big delivery and this is a slow time of the year. People are always like, “Oh my gosh, there’s vacancy in December.” Well, who’s going to pack up and move this time of year? I mean look outside. But what’s interesting is we currently have 600 units under construction. There were 302 permits last year in Des Moines for multifamily and Hubbell’s name was on every single one of them. For Hubbell, that’s great. It’s a little scary though. … Almost all of those [new units] are market rate. We’re just not bringing on affordable [units], so the good news is we’re [providing] another level of housing that’s been very well received. They are leasing up well, but there’s not that next wave coming on.

Q. One thing that has been written a lot about is that there would be more attainable housing if people who are 55 and older would move out of their houses. Where are those folks going to move to, and will they be able to afford those types of housing?

Levy: The housing that I’m developing for 55 and over is only attainable to a narrow slice [of the population because] it’s very expensive. The clientele that we’re serving want the following things, which I think is generally true of downsizers: They want indoor-outdoor living. That means a balcony that’s [good sized]. They want pets. They want a lot of light so you’ve got to put some metal on the walls to support all the windows you’re going to put there. They want a very nice kitchen for entertaining, so you’ve got [to include] a nice big, granite countertop. They want lots of storage, so there’s going to be even more kitchen cabinets than normal. They want 1,300 square feet at a minimum if they’re downsizing from a house. It’s pretty high rent. … So, you start to do the math and you’re trapped in your home. … I don’t think that there’s an easy answer.

Q. What is being done to think about development in a way that ties it into the public transit system so that additional burdens aren’t placed on our already cash-strapped service?

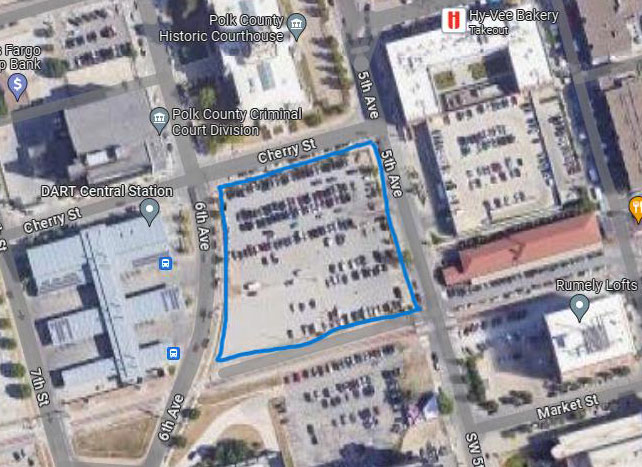

Lynch: One of the things that the city of Des Moines identified with their latest comprehensive plan a few years ago was … the need to build denser housing along corridors where transit already exists so that we can support the transit network and also make it easier for those who need to use it to access it. [The city has] codified that now in the new zoning code. One of the things [the new zoning code] has done is rezoned property along a lot of those major corridors where the transit routes are located to make multifamily development doable by right. [That means] there are less hurdles for a developer to jump through in order to do that; there are still, of course, some challenges with land assembly and some of those other things, but trying to encourage that and make it easier to do.

Q. Why aren’t more developers offering more affordably priced residential products if there is demand for it?

Burmeister: I think that more developers will get into that price point. [Home] builders have been really lucky coming out of the recession … [because] they’ve been building in a very profitable, very comfortable price point for them, and there’s been a market for that. People don’t do things that are new or uncomfortable unless they can’t do things that are easy and comfortable. I think we’re getting to a point where if you want to continue in the construction business you’re going to have to take a look at the market that is really being served, or needs to be served.

Q. What are your final thoughts on affordable – or attainable – housing?

Saddoris: [Everyone should] understand that most of us live in one of the biggest subsidies that the U.S. government does. We all write off our mortgage interest. Literally, that’s one of the biggest [subsidies] we have. We all started somewhere. None of us came out of college [with a lot of money] … we all lived in affordable housing. …Talk to your neighbors. Talk to your employers. Talk to your friends. Talk to your elected officials, because at the end of the day [attainable housing] has to become policy. For those of us that work in this every single day, it’s tougher and tougher and tougher and tougher. We need better policy decisions, we need better leadership – but have the conversation outside this room.

Lynch: And to add on to that, it’s a complicated issue where you can come at it from a lot of different angles. I think just one closing thought, from my perspective, is on the affordability front, or the attainability front: New construction isn’t the only part of the solution. We also need to look at existing housing as part of that solution because it will naturally become more affordable over time. The question is how do we continue to reinvest in that existing housing, whether it’s apartment buildings or single-family so that it still continues to offer a good-quality living environment and doesn’t become affordable because it’s substandard.

Champ: [We need to] make it personal. One of the things we did with our elected officials and leadership staff as an icebreaker [was to] tell your housing story: Where did you live? Where did you grow up? What was your neighborhood like? What did you like about it? What did you not like about it? What’s interesting is it’s different for everybody. Everybody’s had a different experience, but to everybody it is very personal. Then you learn that people that you might never suspect … lived in affordable housing, or subsidized housing.

Burmeister: Plan. Plan. Plan. As we go forward now with the workforce housing study — and the strategies to address that workforce housing study — the one underlying foundational thing that we’re going to be asking of all communities is to get a housing plan. Get it written down, which some communities have already done. … Get it on paper. Decide what your principles are going to be as a community and then begin to talk about strategies to execute. Make sure that we’re not just following the old rule that we’ve followed for far too long, which is “Well, the market will decide.” The market won’t do it. We need plans here to make sure that we have the kinds of housing that folks need and that’s attainable.

Levy: [Instead of trying to] plow forward [with a proposed development] with a neighborhood, approach the neighborhood. … Sometimes it backfires … but for the most part I think it’s a good plan. Generally, there is some kernel of truth to all of the neighborhood objections, and if you can … consider that to be free advice and sometimes make your project better as a result.

Webster: I really liked what Kris said about being able to write off the interest on your mortgage and having that tax deduction. And if there’s anything as far as a piece of advice — own real estate. Own real estate, make your payment, retire the debt and it’s probably one of the single biggest ways that the normal everyday average Joe working for their money can build wealth in this country.