Land Roundtable Q&A – 2020 Annual Real Estate Magazine

KATHY A. BOLTEN Apr 20, 2020 | 4:31 am

19 min read time

4,619 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Real Estate and Development

In 2019, Des Moines University paid $8.5 million for West Des Moines farm ground on which to build its future campus, according to Dallas County real estate records.

The price tag of $95,830 per acre is the highest recorded in Dallas County in the past three years for transactions of 50 or more acres, according to assessor records.

The surging prices of undeveloped ground is surprising, said Clyde Evans, West Des Moines’ director of community and economic development.

“The price of greenfield sites has just gone way out of proportion to what their economic value is at this point in time,” said Evans, a member of a panel that discussed the land sector.

Some landowners are holding on to their properties until the right price is offered, said Chris Della Vedova, senior principal and president of Confluence Landscape Architects and Planners. Landowners say, “‘We’ll let it sit there until someone does come and pay my price.’ Eventually someone comes along.”

The high land prices contribute to gaps between available funds and the development costs of a project, said Jackie Nickolaus, vice president of development services of Benchmark Real Estate Group. “It makes it difficult for a city to come up with incentive programs because what they’re really funding is that high land price versus the cost of construction.”

In May 2019, Des Moines University bought the 88 acres on the northwest corner of Jordan Creek Parkway and Grand Avenue from W&G McKinney Farms LLC. Dallas County had at least eight land transactions for $90,000 an acre or more, records show.

Des Moines University plans to relocate its campus from 3200 Grand Ave. in Des Moines to West Des Moines.

Read the discussion:

Q. What are the most important factors affecting land development in 2020?

Chris Della Vedova: The most important thing that we’re seeing … is some of the uncertainty out of the marketplace. We’ve got a lot of stuff queued up. We probably have more projects on the books than we’ve ever had at this point in the year, which is a good thing. But I think it’s that that uncertainty out there right now is one of the big factors that will impact 2020.

Jackie Nickolaus: I see one of the major issues heading into 2020 is still the cost of construction, both from a labor side and from a material side. It plugs into that uncertainty that Chris was talking about. But labor shortages are increasing the cost of labor and then with tariffs and just material cost increases. It’s hard to keep pace and know exactly how much a project is going to cost.

Clyde Evans: I think the investor confidence [in an issue affecting land development]. We were coming off our second-best year ever in terms of construction activity. I think there’s a lot of uncertainty out there on whether or not the market is going to continue to sustain itself through 2020 and maybe even in 2021.

Q. The uncertainty that you’re talking about — can you talk about what some of those factors are that are leading to that uncertainty?

Evans: I would say labor costs, where interest rates are going to go. There’s been a lot of push to lower interest rates, even have negative interest rates. We’ve seen projects where within one month, the cost of steel has gone up 38%. That is hard to build into the equation when you’re looking at doing a project.

Della Vedova: To add on to that [because of the tight labor market], can projects get built in a timeline that makes it economically viable still? We’re seeing prices coming back at least 30% higher than what we thought they would be six weeks earlier.

Q. Is that 30% higher because of the labor market?

Della Vedova: It’s a combination of everything. … Steel has been a huge driver in costs. One of the things I’m seeing a lot of … is the idea of modular construction. Is that going to get into this market like it has in some of the others. Will that help some of the costs?

Q. Explain modular construction, please.

Della Vedova: One article I just read talked about a hotel in St. Louis [at which] all their bathrooms were built in a factory, brought on-site, set and integrated. They were able to meet their schedule because they didn’t have any lost days due to weather or anything else.

Nickolaus: You’re also seeing, as close as Kansas City, modular apartments and hotel rooms where they construct the entire room off-site or the entire apartment off-site and they connect them together and then they only have to [build] the common areas on-site. Typically, in that situation there’s two general contractors, which makes it complicated. … One of the things I started researching is that a lot of those manufacturing facilities don’t have the capacity [mostly] because of the labor shortage. One of the plants was in Nebraska, and they were running triple shifts to get this hotel done in Kansas City. That’s not sustainable. That’s part of the problem. If you don’t have enough labor, it doesn’t matter if you’re building it outside or inside a modular factory … it’s going to be [hard to get the work done].

Della Vedova: Right now, all the indications for us are just a backlog of work. Now all of that can always go on hold through the end of 2020 and maybe into early 2021. Again, that’s part of that uncertainty that we talked about at the beginning. Nobody really knows. I think one [question] is “What is the level of slowdown when it happens.?” We’ve been discussing when the slowdown is going to happen for multiple years now, but I think the bigger thing there is going to be, is it a slight correction or do we have a major backslide?

Evans: I think also something that will affect when we may start seeing a slowdown is if we start seeing the population growth of the metro start to slow down. As long as we still have a lot of people moving here that are needing housing and services, there’s still a market that is needing to be filled. We don’t really have an oversupply of much of anything.

Della Vedova: Everyone is doing their full due diligence, really looking at things. I think even stuff we’re seeing coming on right now, they’re looking a little closer than they would have a couple of years ago. … Everyone’s definitely a little more cautious than maybe they’ve been in the past. I think some of that’s driven by the lending side as well. Everyone’s real interested in what things cost, and you look back, I’ll say, to 2008 or 2009 leading into that, there was a lot of stuff coming in the door that even me as a landscape architect went, “How’d they get money to do that?” So yeah, I think people are smarter than they were.

Q. Are you seeing any new players come into the market that are changing things?

Evans: We’re actually starting to see more out-of-state investors coming into the market looking to invest. They think Iowa’s an unbelievable place to invest compared to what kind of costs they may have in San Francisco or in New York to buy a property or to renovate it. [The prices here are] considered bargain-basement prices.

Q. A lot of attention has been paid lately to stormwater detention. What’s changed?

Della Vedova: I think the biggest change is about stormwater quality. The quantity requirements have always been in place, but it was really how efficiently can we hold this water and then get it gone. Now it’s, what is that water quality? How do we impact that, whether it’s through green measures or other things. I think the other thing we’re seeing more of is really not thinking on a site-by-site basis, but trying to think a little bit more regionally.

Evans: Probably one of the bigger issues for us in redevelopment of the University Avenue corridor is most of that property was developed in the 1970s when there were minimal stormwater requirements. Now you have properties wanting to redevelop and we’re requiring them to [follow] today’s standards in terms of the stormwater requirement. We are looking at more of a regional approach to stormwater management between us and the city of Clive. There’s a lot of issues that we need to fix, and I think we’ve got a pretty good plan to go forward with doing that. It’s kind of a new way of thinking about things.

Nickolaus: To build on that, we work almost exclusively in the redevelopment space and it is challenging because several of our properties are located in areas that were developed in the 1960s and 1970s where the stormwater requirements weren’t at the level that they are today. You go in and you deal with four- to five-acre parcels surrounded by other parcels that [if undeveloped] would have the same requirements we’re required to meet. The water still runs the same. It runs right over you and down the hill. You still have to figure out a way to accommodate that. It’s all expensive and it all adds to the cost of the project. … When you’re dealing with redevelopment and you don’t know when those properties adjacent to you are going to be redeveloped, it becomes hard to develop that approach that will assist everybody in the area.

Q. What does stormwater retention look like? Does that mean less paving? Walk us through what it looks like going forward compared to what it used to look like?

Della Vedova: I would like to say it’s less paving. In reality it’s not. For projects to work, you have to have a certain number of parking stalls. … Nobody’s out there who wants to spend more than they have to. What you’re seeing is kind of right-sizing. We are seeing more shared parking uses; shared uses where we can try and reduce some of those parking counts, which then has an impact on stormwater. We’re seeing a lot more in the metro, just underground storage. It’s not all in ponds anymore. While it’s an expense, it’s becoming more cost-effective. … As far as the solutions, it’s trying to be creative. We’re doing a project right now – Johnston’s town center — where we’re doing some demonstration islands. … It doesn’t just have to be a grass mound. We can take those areas and start to use them. Every bit adds up when it comes to stormwater. … The old system was how fast can we get it to an intake? How fast can we get it into a pipe? How fast can we get it to the river? Now you’re seeing a lot of … bioswale or something that helps slowdown that flow, filter that flow.

Nickolaus: I think the operative word that [Della Vedova] said was right-sizing. I think the approach that really helps is for the cities and for the developers to work together to think of parking solutions and storm management solutions that maybe can evolve. Nobody wants to put the storm management underground and pave over it and then find out no one ever uses those 55 parking spots anyway. I see the opportunity to start with above-ground detention and then if that doesn’t work, have an understanding that then that will go underground and more parking will be added. … The problem is strict parking restrictions. The formulas don’t necessarily work and you can’t apply one situation to another. If the developer and the city work together and agree over time, then we have more flexibility. Believe me, the last thing a developer wants is that their development is under-parked because that is so hard to market if you don’t have enough parking. However, again, you don’t want to have 55 vacant parking spots that sit there every day and you’re sitting there looking at that underground storage going, “That cost me a lot of money.”

Q. That’s got to be tough when we’re trying to create more walkable neighborhoods and areas. We have vehicles that are becoming autonomous, and in five years there won’t be as many vehicles on the road. How do you balance all of that?

Della Vedova: Flexibility. Just taking that phased approach and [understanding] things are going to change and we have to anticipate what we can, but we’re not going to anticipate everything. When things come up, figure out what to do. We hear a lot about autonomous vehicles. I’m a little skeptical personally; even if there’s an autonomous vehicle, there’s still those daily trips that people are going to want to take. Those vehicles are still out there, and if they’re not parking, then where are they going? So that’s not going to solve everything in the next five to years.

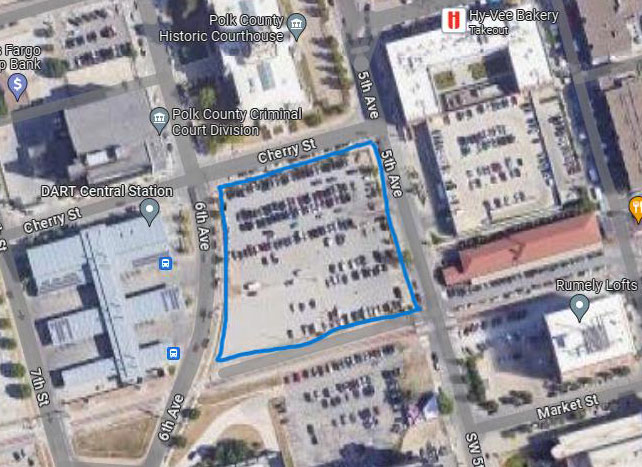

Q. We’ve got several areas in the metro that are going to be redeveloped: the University Avenue corridor in West Des Moines, Eighth Street in West Des Moines, the Market District in downtown. How do you go about doing that redevelopment?

Evans: I think at least from West Des Moines’ perspective, we realize that the parking standards we have now are parking standards for the 1970s, not 2020. I think we’re going to probably be more flexible in taking a look at how much parking is actually on a site. We certainly don’t want to have … those 55 parking spaces that never get used. I think there’s going to be a lot more thought given to “OK, how much parking do we really need without causing congestion, but a little bit congestion is not terribly bad either.”

We had a recent project that is looking at doing a new building on an existing site. They were going to do a parking ramp, but they structured the parking ramp such that … decks are all level rather than sloped. Their feeling is at some point in time there’s not going to be the vehicles coming to the site and they can convert that parking ramp to a future office building. They were more concerned about having a large enough drop-off area for people that were coming there for services and stuff.

Q. As we’re redeveloping areas, are we going to see streets turned into pedestrian areas? What are we going to be seeing that we may not have now?

Evans: Hopefully, we learned the error of our ways when we started making everything [pedestrian] malls. I come from a community in Illinois that they probably made every bad planning decision you could and the biggest one they made was turning the main street in town into a ped mall. Now, that’s not to say that the streets won’t get a little narrower and a little friendlier, but it shouldn’t have to be a 100-yard-dash to try to get across the street on the walk light.

Della Vedova: The metro area [needs to start] getting streets right-sized. We don’t need six lanes of traffic everywhere. Getting things narrowed down, giving the pedestrians more space. But I don’t see it ever where the street components are going away.

Nickolaus: You see that the city of Des Moines has been looking at the Douglas Avenue corridor. … Anytime you start looking at large areas to redevelop, the more challenging it is. But a huge challenge there is that Douglas and Euclid are a state highway and people just drive down that at a high rate of speed. How do you right-size it, and how do you slow down the traffic so that businesses can be successful? If you’re going down the street at 45 miles an hour, you don’t see the storefronts. If you do see what it is and you think you want to stop by tomorrow, you don’t have a place to park. It’s figuring out the right balance so you can still move the traffic and then sell the citizens on the fact that it may take them a whole five minutes longer but look at what your benefits are.

Della Vedova: I think Clyde put it well — a little bit of congestion is the level you want to get to. … All this ties back to the infrastructure. So that’s roads, the stormwater that we talked about, sanitary sewer. All of those things.

Evans: California tried to build their way out of traffic congestion; they found out they couldn’t do it. Every time they added more lanes to the freeway, they just had more congestion. You start having to look at alternatives to continuing to add more lanes.

Q. Are there some things that you see communities doing that you say, “I really wish they wouldn’t be doing those things in the future” because they’re going to cause potential challenges in the future?

Della Vedova: I think there’s still a tendency to potentially over-park. There’s a tendency from an infrastructure standpoint, particularly with cities that we’re starting to see a shift. I’ll use stormwater. For a long time it was the belt and suspenders model. “We’ll try your new idea, but you still have to put in an intake and lots of pipes,” which then didn’t make it economically viable to try something new. We’re seeing all the communities in the metro definitely taking a more open mind to what are some things. There always is room for more. … I think the other piece of that is seeing property owners who won’t work together. From my perspective, one of the big stumbling blocks that we run into, particularly in some of these corridor developments, where you’ve got lots of different owners and who could benefit from some shared parking agreements or cross access agreements but they don’t like someone so they won’t [cooperate].

Evans: When we were doing all the development around Jordan Creek, we wanted to try to be very flexible in how somebody developed a piece of property. We finally had to get a lot of pretty pictures out to say, “Hey, you could do something like this on your property.” They go, “Oh yeah, I know where that is. That’s in Scottsdale,” or “That’s in Florida.” Sometimes it was their consultants holding [the owner] back from doing something differently because the consultants knew [they could get a project through the city] approval process within the least amount of effort and the least amount of time.

Q. Are there incentives cities might have to provide to landowners to get them to start looking at their properties differently to spur redevelopment?

Evans: I think certainly incentives would be one thing we’d take a look at — the carrot and stick approach. In order for that property to be redeveloped, maybe it needs to go to a residential designation. Maybe we’ll give you more density to be able to get the values you think the property is really worth. I think also it’s an educational process to be able to show them that how they can continue to do what they’ve been doing but that commercial center is going to continue to diminish in value to the point where it’s not really worth a lot.

Q. What isn’t being done in new developments today that people might regret 10 years from now?

Evans: From what I’ve heard from people, it’s fiber. When you take a look at the typical user in the metro area, they’re typically an office user. They don’t need a lot of water. They don’t need lots of sanitary sewer, but they live and die by the amount of broadband that they potentially have available to them. And as our economy becomes more and more interconnected, global speed of communication is going to be critical for everybody. One of the reasons I think that the Des Moines area has been so successful is the amount of long-haul fiber we have coming through the metro area. I think that’s helped us out a lot.

In West Des Moines, one of the biggest problems that we have, and I think a lot of other communities have, is that public right of way. You’ve got 30, 40 different fiber lines in there. It gets to a point where on some of the major roadways there’s no room. Companies are having to cross at the middle of the block rather than to corner because again, there’s no room there. We’re looking at ways to be more efficient in the use of the right of ways.

Nickolaus: One of these things in redevelopment that’s really important … is trying to expand connectivity. Eighth Street is a good example. It’s an area that had a lot of activity; declined over a few years. We’re building about 80 residential units; we’ll bring activity back. But how do you link those people to other areas in the community? We’re consciously not putting a big fitness area in because we want them to go to the Y. However, try to walk between the south side of Eighth Street and the north side by Walmart. It’s challenging on any day. So then how do you work with the cities to build that connectivity in? Anybody that lives in those units, if they could get to the trail, they could ride their bike to downtown to work. But you have to build that connection.

Q. We talked about out-of-state investors earlier. Could you talk a little bit about what effects we might see that having on the market here?

Evans: A big concern of mine would be that out-of-state investors need to be involved investors. We don’t want to see somebody come in, buy a piece of property and forget it. We’ve seen that happen at times. I think we’ve been blessed with having a lot of really fantastic local ownership that takes a great deal of pride in their properties.

Q. When you see those out-of-state investors come in, what are they looking for here?

Nickolaus: Some of them are building existing portfolios, whether it’s residential buildings or office centers. We’re noticing there’s also out-of-state investors interested in new projects, small projects. We do small projects and there are many out-of-state investors and financial advisers that are assembling pools to invest in small real estate projects in Iowa. Those people are going to not be as active as if they bought a property or are running it. They’re bringing critical equity to projects to bring them to the finish line.

Q. We’re seeing land prices increase. What effect is that having on developments?

Nickolaus: Particularly in the redevelopment world, it has a huge impact. I think Clyde said it earlier, a property owner believes their property is worth X. It’s been in decline, but they still think it’s worth X. So when they sell it, they expect X. … It’s not reasonable.

Della Vedova: That’s probably one of the biggest things we face when we come in to do a plan, particularly on a corridor: Everyone thinks their property is the absolute most valuable property in the corridor.

Q. What are developers asking for in the way of incentives?

Evans: [Developers] want property tax rebates or abatement. [West Des Moines does rebates but not abatements.] Most of the major developers think it’s almost by right that we’re going to give them five years or 10 years of 100% abatement or rebates and we’re going to put in all of the infrastructure. [If West Des Moines doesn’t do it], they say they’ll go to another community because “They’ll do it for me.” That puts a community in a really tough spot if you’re trying to retain those jobs in your community, retain a really good employer that’s been a very big part of your community. You either say, “Bye,” or “Well, OK, we’ll work with you on this.”

Nickolaus: I do think, more from the state perspective than a local perspective, that your brownfield and grayfield tax credit program could be much more effective if it didn’t have the low annual cap on it. There are many sites on those corridors that would qualify for grayfield or brownfield but the pot gets used up too quickly and there’s really no other resource to replace it. You have a lot of corners where the gas stations were or auto repair places that could be redeveloped if there was just that little extra push and they could access as extra funds.

Q. What sort of sustainability features are you seeing in new or redeveloped areas?

Della Vedova: It’s not just about green, but it’s about what is the long-term viability of the project. It’s not just how green do we make it, but can this project sustain itself over the long term?

Nickolaus: I think the perspective of looking at an infill site and recognizing the sustainability of that site versus the actual features of the building. If you can build 80 units on a corridor where there’s better transit or better access to trails or has more walkability, that [would be] more sustainable than maybe a project on a greenfield where people have to drive everywhere. … That said, we’ve been talking about the cost of construction and unfortunately a lot of sustainability things still take extra funds.

Q. Is there anything that causes you concern?

Nickolaus: I think that as a metro we sometimes forget that we’re very linked to our agricultural community. I do feel that any prolonged downturn in agriculture will impact us.

Evans: A concern for me would be if you start seeing employers saying, “This market doesn’t work for me because I can’t find the workforce.” And then they start saying, “I’m going to open up a satellite facility in Denver or Phoenix.” From what I’ve heard from my associates out there, everybody’s got the issue of not being able to find the right skilled workers. I think it’s incumbent upon all of us to work together to make sure that we’re able to continue to develop that workforce that our companies are needing.

Q. What are your closing thoughts?

Evans: Overall, I’m pretty optimistic in terms of where I see the economy for the rest of this year and even into a good part of next year. I think a lot will depend on which way the national elections go and how people feel about that. From what we’ve seen and the projects … that we’ve got going on, I think there’s still a lot of interest in developing and there’s still the need here. It’s not one of those situations like, “OK, we’re going to go build another strip center that we really don’t need because there’s not the retailers to fill it.” There is still that need for housing and for retail development. It may not always be where it needs to be, but I think we’re getting better at figuring that out.

Nickolaus: I’m optimistic about the near future for development. I’ve been through cycles in Des Moines. Our lows aren’t terribly low; our highs aren’t terribly high. We’re stable. We continue to grow and I think there’s exciting opportunities and a lot of forward motion on both improving our suburban communities as well as Des Moines, which strengthens us all.

Della Vedova: I’m optimistic. There’s a lot of good things going on, and it’s around the entire metro. When I was kind of looking through our backlog at work … we have projects in every corner of the metro, not just the west or north or south. It’s all over the metro that everything is strong.