Maternal health symposium highlights access challenges, proposes new solutions

Kyle Heim Nov 17, 2023 | 6:00 am

7 min read time

1,667 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Health and WellnessAccess to maternal health care services is becoming an increasing concern in Iowa, as the number of counties in the state operating without an obstetric unit has increased by 157.14% since 1999.

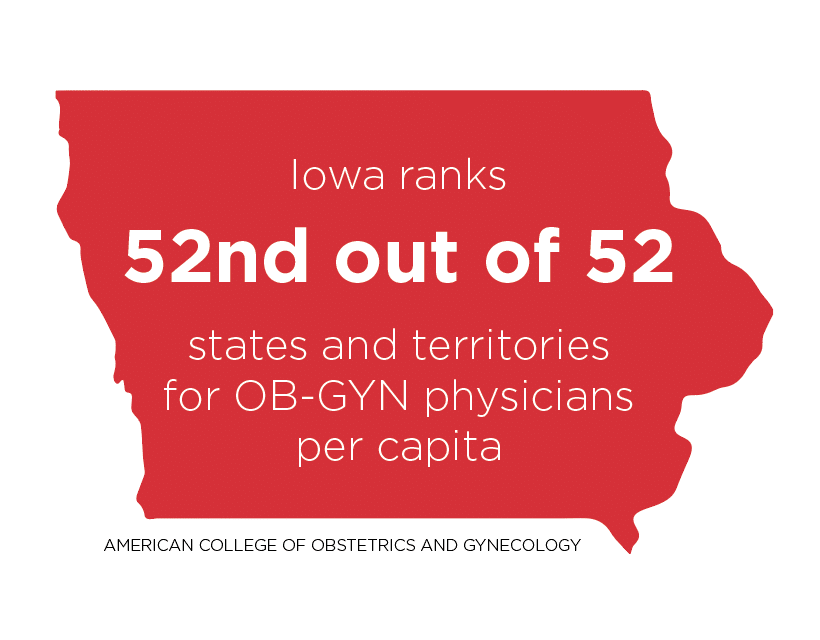

In addition to the rising number of obstetric unit closures – 42 shut down between 2000 and 2021 – Iowa ranks 52nd out of 52 states and territories for OB-GYN physicians per capita, according to data from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Coinciding with increasing obstetric unit shutdowns and widening workforce gaps, Iowa’s maternal mortality rate more than doubled between 1999 and 2019, a July 2023 JAMA study says. A maternal death is defined by the World Health Organization as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.”

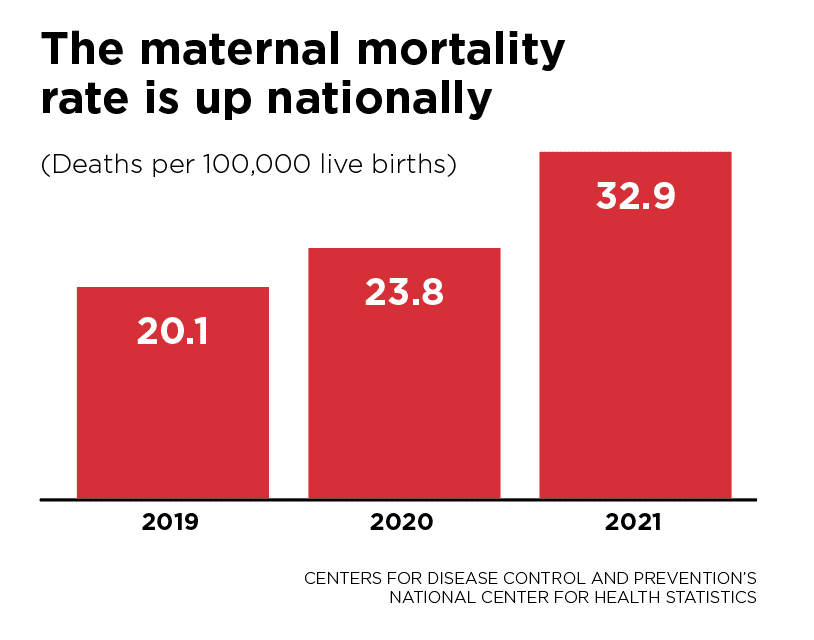

Nationally, the maternal mortality rate for 2021 was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, up from rates of 23.8 in 2020 and 20.1 in 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics.

The closures and lack of OB-GYN physicians in the state have created a “crisis of access,” Stephen Hunter, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, said, driving an “immense expansion of obstetric deserts in our state.”

Hunter was one of more than a dozen health care professionals who shared current data and trends, as well as proposed solutions for addressing some of the greatest challenges related to maternal health in Iowa, during the Bridging the Gap: Improving Maternal and Rural Health Symposium on Oct. 30 in Ankeny.

Hosted by Healthy Birth Day Inc., the daylong event covered the landscape of Iowa birthing centers; innovative clinical approaches; health equity, access and improvement; access to maternity care and evidence-based supports for maternal and infant health in rural areas; maternal morbidity and mortality in Iowa; prevalence, causes and policy solutions for maternal morbidity and mortality in rural areas; and community-based solutions.

Hunter presented what he believes are the top five Iowa maternal health care issues: workforce, education and quality of care, data, communication and coordination, and access to care.

At a conference in Des Moines shortly before COVID-19 became a major public health issue, Hunter said he held an event for all of the CEOs of hospitals to talk about maternal health. In a survey he conducted, one question he asked was, “Do you have concerns regarding the continued viability of your labor delivery units?”

“[These were] CEOs of hospitals that had labor delivery units,” he said. “And 34 of the 55 said yes. Well over 50% said they were concerned about the viability.”

Preliminary data for 2023 released by the Association of American Medical Colleges showed that the average number of applications per obstetrics and gynecology residency program fell from 663 in 2022 to 650 in 2023.

OB-GYN workforce shortages and a rising number of obstetric unit closures have coincided with countrywide increases in cesarean delivery rate, preterm birth rate and low birth weight rate, all of which can increase other health risks and require specialized care, according to a National Vital Statistics Report from January.

The study found that the cesarean delivery rate increased to 32.1% in 2021 from 31.8% in 2020, marking the second increase in a row after the rate had declined in 2018 and 2019. The preterm birth rate (percentage of all births delivered at less than 37 completed weeks of gestation) rose from 10.09% in 2020 to 10.49% in 2021, the highest level reported since at least 2007. The percentage of infants born with a low birth weight – less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces – rose from 8.24% in 2020 to 8.52% in 2021.

In addition to an association between labor and delivery unit closures and poor outcomes, there is also an association between poor outcomes and higher costs.

Hunter said for businesses, that could mean employees needing to spend additional time in the hospital and out of work.

“Good perinatal outcomes should be important to businesses because bad outcomes cost money,” Hunter said.

“If [mothers are] sick and they’re in the hospital, they’re not working. They’re in the hospital. If they have a bad outcome, and their baby is in the [neonatal intensive care unit], they’re not at work; they’re in the hospital,” he said. “Bad outcomes always cost more money, and they cost not just Medicaid, they cost the entire society more money. And that’s why businesses should care.”

Not only does the quality of care affect businesses, and society as a whole, but the lack of labor and delivery services in a county could be a determining factor for a family deciding where to live, Hunter added.

“If they’re a young family and they’re starting out having kids, and they can’t get labor and delivery services there, they may choose not to live there,” he said. “And that might be the first step of that town’s demise. On the flip side, it could be a sign of the deterioration of the town – they no longer have enough young people having babies just to maintain and support labor and delivery. I don’t know the answer to that question, but it’s an interesting question.”

Current efforts

With the rise of labor and delivery unit closures, as well as worker shortages, has come new efforts to improve maternal health care in Iowa. One of those is the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics’ nurse midwifery education program and clinical practice.

A Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal Health Innovation grant in 2019 kick-started the development of the program, with the initial round of funding used to hire a consulting group to help complete a feasibility study and needs assessment for the program. Pre-accreditation status was granted in 2022 and the first class started this year.

An Iowa certified nurse midwife must have a bachelor’s degree in nursing or another field. They must also have a master’s degree or doctorate degree, which can be in any field.

In addition to the education requirements, a certified nurse midwife has to be a registered nurse, which requires passing the National Council Licensure Examination.

“I would say that midwives in general kind of have convoluted paths to becoming a nurse midwife,” Lastascia Coleman, certified nurse midwife and clinical associate professor in the Carver College of Medicine at the University of Iowa, said. “For state licensure, Iowa certified nurse midwives are licensed as advanced registered nurse practitioners. And we have full prescriptive authority. We also, prior to becoming licensed, have to take the national certification exam, and we recertify every five years.”

The roles of nurse midwives expand beyond pregnancy, birth and postpartum care.

“We can also do a lot of other things,” Coleman said. “So I have a lot of patients who I’m their primary care provider for. We can do gynecologic care, we can do contraception management, we can also take care of newborns up to 28 days.”

According to the United Nations Population Fund, “Midwives can meet about 90% of the need for essential sexual, reproductive, maternal, newborn and adolescent health interventions.”

One way that technology has played a role in improving maternal health care is through an app called Count the Kicks, which helps pregnant people during the third trimester record how long it takes for their baby to reach 10 movements, tracks changes over time and reminds them to count every day.

“We have developed the Count the Kicks app to meet the needs of parents who want to monitor their baby’s movement,” Christine Tucker, health equity coordinator for Count the Kicks, said. “What really sets us apart from other pregnancy apps is that our app is free. It’s got no pop-ups, no ads, it’s available in 16 languages, and more to come as well.

“Parents get this visual feedback after their counting sessions, so they know if their graph is staying level, that’s a good sign. But if we see a spike in the amount of time it’s taking to get to 10 movements, then they need to speak up to their doctor or midwife.”

Count the Kicks also provides downloadable paper charts and web-based counters on its website to expand accessibility.

“There are a lot of ways we approach this work,” Tucker said. “We have the paper charts and movement monitoring bracelets for rural areas with less access to Wi-Fi and data that we primarily distribute through home visiting programs.”

Count the Kicks advises pregnant people to start counting between 26 to 28 weeks, when there’s a consistent movement pattern, and spend time once a day with their baby checking in to see how long it takes them to get to 10 movements.

Proposed solutions

If given the opportunity to start from scratch with available resources to tackle the greatest concerns with maternal health care in Iowa, a solution that Hunter proposed was placing hospitals that would include everything for a high-quality labor delivery unit in strategic locations throughout the state.

“24/7, physicians, well-trained nurses, anesthesia, blood bank, imaging, it’d all be there,” Hunter said. “And then, in the outlying communities, and we’ve heard hints of this today, we’d have prenatal care.”

Any effort to improve maternal health care, though, is going to require money, Hunter said.

“Just know that everything I’m talking about takes money,” he said. “Everything talked about today, and there were some great programs out there, takes money. And everybody has to have some skin in the game, including the patients. I was glad to see some of the programs gave gift certificates after completion of certain requirements. That’s skin in the game.

“Everybody has to have some skin in the game: patients, patient families, health care providers, health care organizations, state and federal government, everybody. And it’s got to be a team effort, or it’s going to fail. Guaranteed.”

Kyle Heim

Kyle Heim is a staff writer and copy editor at Business Record. He covers health and wellness, ag and environment and Iowa Stops Hunger.