Mercy College of Health Sciences announces campaign to raise $15M for new nursing school as part of its mission to become the ‘school of choice’

Michael Crumb Feb 6, 2025 | 4:00 pm

9 min read time

2,064 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Education, Health and Wellness, Real Estate and DevelopmentJoyce Lillis was inspired to become a nurse after watching the care her mom received after suffering a stroke, and later as a senior in high school, Lillis’ appendix ruptured and she was hospitalized for three weeks.

Now, after a nearly 40-year career as a nurse, Lillis’ name will be attached to a new building at Mercy College of Health Sciences dedicated to training the next generation of nurses and helping fill the need for nurses across the state.

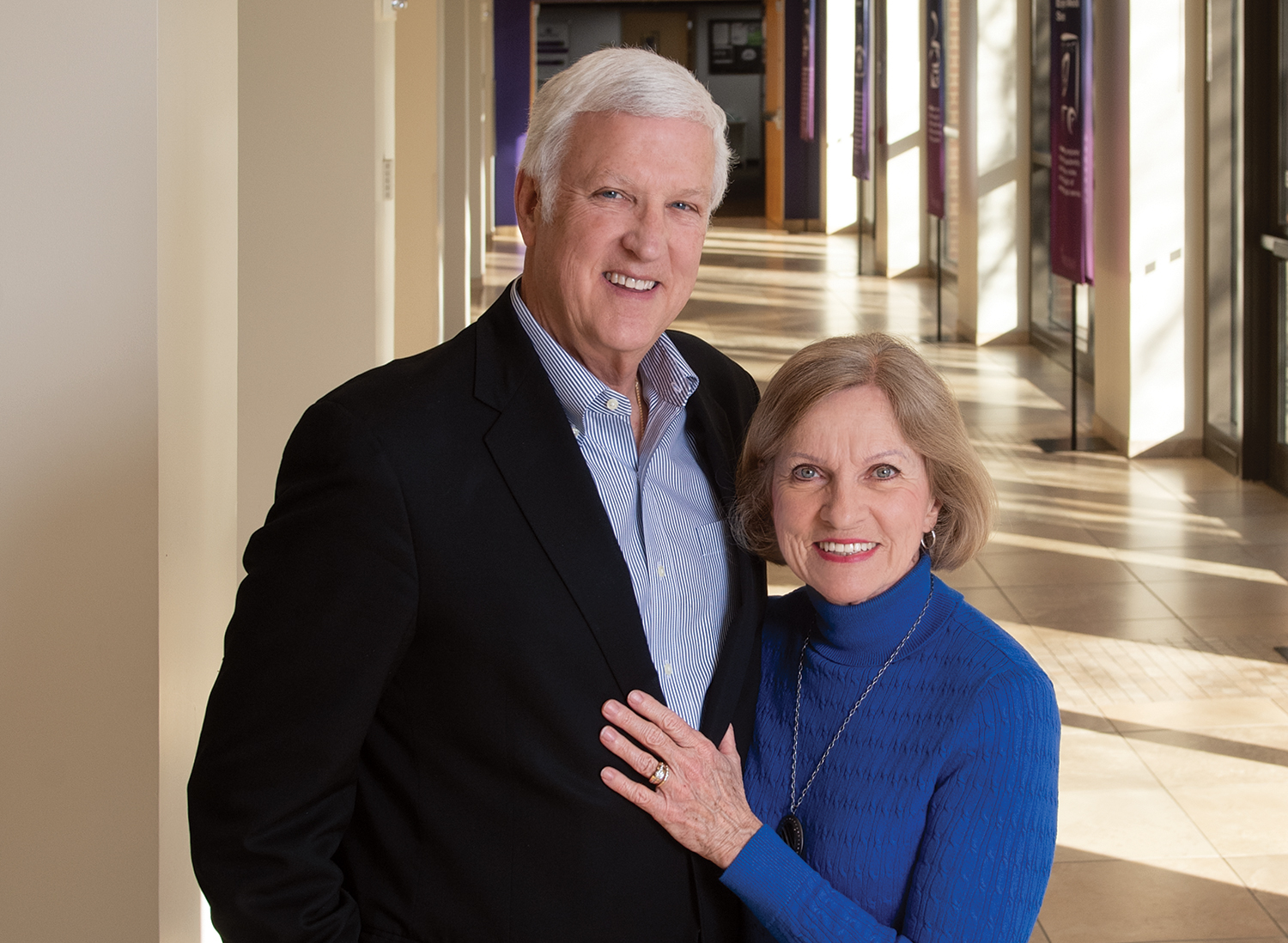

Mercy College has launched a $15 million campaign to build a 24,000-square-foot building on its campus along Seventh Street, just south of Interstate 235 near downtown Des Moines. So far, nearly $8 million — including $2.5 million from Joyce and her husband, Terry — has been raised through the silent phase of the campaign, and college officials are confident they will be able to raise the remainder needed and begin construction in 2026.

The project

The Joyce Lillis School of Nursing will replace a current 12,000-square-foot building on the Mercy campus that has remained vacant since 2018 when it was decommissioned after it was deemed unfit to use for classes. It still is used for storage. No staff or programs are housed there, said Dr. Adreain Henry, the college’s president.

The building that will be razed to make room for the new nursing school is an eyesore for the college and Des Moines, and Henry believes that the new building will not only help Mercy expand but also be a catalyst for other improvements and growth in the neighborhood.

The new building will include the latest technology and equipment to enhance the college’s ability to graduate top students to fill the more than 3,500 openings for nurses listed on the Iowa Workforce Development website.

The capital campaign, which has entered its public phase, is the first of its kind for Mercy and construction of the Joyce Lillis School of Nursing will be 100% funded by philanthropy, Henry said.

“We set a budget goal of $15 million … and I have to tell you for Mercy College of Health Sciences that is really high because we’ve never raised that type of money before,” he said.

The capital campaign began with the Lillises’ $2.5 million donation, the largest gift in the school’s history.

Henry said Mercy approached the Lillises about putting Joyce’s name alone on the building and Terry happily agreed.

Mercy College wanted to build an “inspirational facility,” for its nursing students, and naming it after Joyce Lillis will do just that, Henry said.

“When it comes to compassion for service, nurses are the bedrock of our health care system,” he said. “Imagine all the aspiring nurses that will now walk inside a brand-new building that’s named after a nurse, and think, ‘If she can do it, I too can do it.’ We wanted to have that type of impact on our future students.”

The decision to donate

The Lillises said contributing to the new nursing building was an easy decision.

Joyce, who spent nearly 40 years as a nurse, most of them in the MercyOne system, said it’s important to get more nurses trained, but that there are many challenges in reaching that goal.

Working nights, weekends and holidays is the norm, unless you work in a clinic, and then the sheer shortage of nurses creates stress, she said.

“For example, you’re working, somebody calls in sick and they don’t have anyone to fill in, so you are working two people’s jobs and you get that done and the hospital thinks if you did it yesterday you can do it today and there is a lot of burnout,” Joyce said.

During her career, she worked in different capacities as a nurse, including being a floor nurse, a home health nurse and a manager.

She was one of nine children growing up. Her inspiration to pursue nursing as a career began when she was 13 years old living on the family farm near Parnell, a small town west of Iowa City. Her mother had a stroke and was hospitalized for a period of time, going through rehab before eventually recovering.

And then there was her experience after her appendix ruptured when she was senior in high school.

“I was exposed to a lot of nurses and doctors and it gave me an interest that maybe this is something I would like to do in life,” she said.

Joyce, who received her nursing degree from the University of Iowa, remembers one case when she was a home care and hospice nurse that she felt validated her decision to go into nursing.

She said a man was very sick and she felt he was being overmedicated.

“So I really had to work with the physicians to convince them and slowly he recovered,” Joyce said. “His family put me on this pedestal because they thought I really knew what I was doing.”

It’s that advocating for patients and having empathy that makes someone a good nurse, she said.

“The more you understand where that patient is coming from, what their needs are, that’s how you can be caring and you can be understanding and you can be their advocate,” Joyce said.

Terry said when he and Joyce got married he taught at a school in Bode, Iowa, and their first child was born in Kossuth County in Algona. Although she had just delivered their first child, Joyce was taking care of her hospital roommate, he said.

“The nurses there were all busy, so she just stepped in and did her job,” Terry said.

Joyce also serves as chair of Mercy College’s board of directors, and is a liaison between the college and the MercyOne foundation. She said in those roles she saw the impact the nursing shortage was having on the health care system during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We had to close beds, and we had no nurses because many of them quit, many that were older retired early, so that situation just exploded,” Joyce said. “We still have all these needs. We have a hospital that has the beds, but we don’t have enough nurses to provide the care for patients that come in.

“We have to attract more nurses to this role,” Joyce said. “We need more nurses is what it all ends up being about.”

Terry, a U.S. Army veteran, first pursued teaching and coaching as a career, but went back to school to become an actuary and later worked for Bankers Life and Principal Financial Group, where he spent 35 years, retiring as an executive vice president and chief financial officer.

He has served on the MercyOne board in several capacities, and said beds that were closed during the pandemic have remained closed because there aren’t enough nurses to care for patients.

He said he and Joyce have been fortunate in their lives and have focused their philanthropy on health, education and faith, and giving to the Mercy College project aligns perfectly for them.

“That’s the sweet spot for all of those,” he said.

When asked about having a building named after her, Joyce became emotional and had difficulty finding the words to describe what it means to her.

“I’m not any super nurse,” she said. “I don’t know. I just felt like I plugged away. I was a nurse.”

The next generation

Brianna Busch is a student in Mercy College’s accelerated, one-year nursing program. She enrolled at Mercy after receiving her bachelor’s degree in human physiology at the University of Iowa, where she was studying pre-med.

Although she won’t be able to take advantage of the new facility, she believes the modern, state-of-the art facilities and equipment will be attractive for others seeking to pursue a career in nursing.

“You can learn a lot in lecture, but what really draws you in is the labs and the realistic situations, high-fidelity mannequins. All that technology in a controlled and safe environment is really important,” said Busch, 23. “It really grows your confidence before you’re put into real-life situations.

“I think people are going to look at the new technology and all that new equipment and it’s really going to attract them,” she said.

Busch said while she believes she’s getting a good education, she acknowledges some of Mercy’s current facilities are dated.

“The [Academic Center for Excellence] building was very attractive when I came and toured. It’s kind of newer, but there are some older parts, such as Brennan Hall, that you can feel are outdated and might be more attractive to newer students if the classroom aspects were a little more updated than they currently are,” she said.

Busch said having a building designated for only nursing programs should also be attractive to prospective students.

“If we’re able to make that separation and really know that this new building is just for the nursing students within Mercy College of Health Sciences, it feels like we have our own personal space on campus downtown,” she said.

Reinventing Mercy

The Joyce Lillis School of Nursing is part of Mercy College of Health Sciences’ mission to reinvent itself and train nurses to help fill the workforce shortages the industry is experiencing.

Henry said it will also free up space for the college to expand its other programs, such as diagnostic medical sonography, medical assisting, paramedic and radiologic technology.

Mercy graduates about 350 students a year, with more than half of those graduating from its nursing programs.

When Mercy opened its Academic Center for Excellence in 2018 it saw an approximate 20% increase in enrollment, and he believes a similar increase could be seen with the completion of the Joyce Lillis School of Nursing.

“When we think about having a self-contained nursing facility in this new building, that frees up some of the other space for us to really begin to think about where are the other in-demand health care careers that we can add,” Henry said. “Adding new programs is where we get the increase in our enrollment and equates to higher graduations.”

Henry started as Mercy’s president on July 1, 2022, and after listening sessions with college stakeholders during his first 100 days, he said he was ready to cast the vision for the school’s future.

That vision? Make Mercy College of Health Sciences “the school of choice,” he said.

“Over the years, we had become the school of default and that’s not always a good thing,” Henry said. “We had become the school of default in a negative way.”

Henry said the perception among hospitals was that the school’s quality of education had declined, a perception that needed to change.

“So part of that was us reinventing ourselves to become the school of choice,” he said. “That means the quality of our graduates needed to improve.”

Another marker was doing a better job of tracking where alumni went after graduation and becoming more engaged with alumni. That led to the creation of a vice president of institutional advancement, philanthropy and community engagement.

“And we also needed to make sure that we were not insulated and isolated from the community,” Henry said. “So we knew that we needed to do a facelift on that part of our practice. We really needed to bolster our philanthropy and be able to get out in the community.”

Those efforts are paying off with the campaign to raise money to build the Joyce Lillis School of Nursing, which Henry said will attract top students and faculty.

“We know that research says about 40% of students place significant importance on their decisions to attend an institution based on aesthetics, how it looks,” Henry said.

Currently, Mercy nursing students are scattered among its buildings. Bringing them all under one roof will enhance the cohesiveness and quality of their education, he said.

Henry said Mercy, which was founded in 1899 by the Sisters of Mercy, wants to become a destination and meet the ever-changing demands of the health care industry.

“And that became our North Star,” he said.

“When people say I want to be a nurse, the first thing we want to roll off their tongue is ‘I’m going to look into Mercy College,’” Henry said. “We want to be that first choice.”

Michael Crumb

Michael Crumb is a senior staff writer at Business Record. He covers real estate and development and transportation.