NOTEBOOK: Behavioral economics helps explain sharp uptick in deposits, drop in bank earnings

JOE GARDYASZ Jun 24, 2020 | 4:45 pm

3 min read time

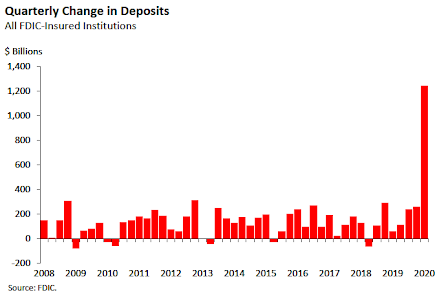

710 wordsBanking and Finance, Business Record Insider, The Insider NotebookAs I was writing an article last week reporting on the latest FDIC quarterly banking statistics, I had to wonder what types of factors weighed into banks experiencing such a sharp drop in earnings nationally. Net income of FDIC-insured banks for the first quarter dropped nearly 70%, even as Americans deposited five times more cash into liquid accounts than they did in an average quarter.

Sure, it was in response to the coronavirus shutdown — but why would a more than $1 trillion uptick in deposits result in a double-digit drop in earnings? I also puzzled over why Iowa banks’ decline in quarterly net income — 8.3% — was about one-tenth the percentage point drop for the U.S. as a whole.

Part of the answer may have arrived in my inbox that same day from an economist who has studied Americans’ financial reactions to recessions.

Geller, founder of Analyticom, a consulting group focused on working with banks to optimize their deposit rates, has presented at national banking conferences and has worked with financial institutions of all sizes across the country.

His theory, which is detailed in a peer-reviewed paper, “Dynamics of Yield Gravity and the Money Anxiety Index,” published in 2018 in the Journal of Applied Business and Economics, states that during economic uncertainty, when the level of money anxiety increases, people reduce their spending and increase their savings.

“People basically hoarded money,” he said in a phone interview. “We call it ‘mattress money.’ They put it aside in liquid accounts so it would be accessible. There is a difference between regular savings and hoarding, which is an instinctive response to financial anxiety and economic uncertainty. Our ancestors used to hoard food and wood in times of fear and uncertainty. Today, we hold money.”

Geller’s research shows that when money anxiety is high, such as during recessionary times, the ability of higher yield to attract term deposits diminishes.

The takeaway for financial institutions, Geller says — and part of the reason that U.S. banks’ net income dived nearly 70% — is that interest rates don’t mean as much to people as they’re scrambling to just find a safe haven for their money. Many banks failed to adjust their interest rate pricing downward for these “mattress money” deposits. As a result, net interest margins for banks overall declined by 0.29% in the first quarter.

“Banks that don’t have the tools of optimization don’t know that, and they are paying the same rate for hoarding as for saving,” he said. “A 29 basis-point decline — that’s a lot. … What happened in the first quarter shows how important this is now, because every basis point counts now.”

I asked Geller why Iowa’s net deposits — which increased by less than $4 billion in the first quarter, or about 5.5% year-over-year — were so much less of a percentage increase than nationally. The difference was largely due to Iowa’s lower cost of living, he said, which made the Money Anxiety effect proportionally smaller.

He compared it to a wealthy individual deciding not to buy the new Tesla sedan, versus a lower-income person deciding not to buy some small item. “So I would say that in the urban areas, especially the large metropolitan areas, there is more disposable income and a greater proportional effect.”

So, is adjusting rates based on the Money Anxiety Index fair to the banking consumer? Geller says it is.

“There is no point in getting better rates with a bank that’s not financially stable,” he said. “[This model] is paying interest optimally to keep the bank financially stable, and at the same time paying the customer the highest possible interest rate under the circumstances. This is why banks love the model — it looks at the economic environment to find the optimal pricing position. I think it’s a plus for the consumer knowing that the bank is financially stable.”