Optimism over projected big yields dampened by fears of drought and continued foreign competition

And then there is the always unpredictable weather. A growing area of drought creeping across the state as the critical pollination phase for corn begins could decrease projected yields, further dampening hopes for a turnaround to the recession that has plagued American farmers since 2013.

Competition

One of the biggest factors driving the farm economy in recent years is foreign competition as other countries, particularly in South America, have advanced their technologies and increased their production. Until U.S. farmers can become more competitive, prices will continue to be down and markets will continue to suffer, said Roger Zylstra, a farmer who grows corn and soybeans, and raises hog and cattle in Jasper County.

“We try very hard to provide a high-quality product at a fair price, but with fluctuations in currency and other things, we’re basically priced out of the market,” said Zylstra, who also is president of the Iowa Corn Promotion Board.

Zylstra said the U.S. agriculture industry will need to reevaluate itself if it’s going to be competitive.

“The world has figured out how to grow corn and soybeans and meat, and we have to be in a position that we can compete with them,” he said. “And that means that our transportation infrastructure needs to continue to be functional and be upgraded. That means that we’re going to have to make some adjustments in all our costs.”

Zylstra said local producers have been hit hard by shutdowns caused by the pandemic, from restaurants and schools to meat processing and ethanol plants. For Zylstra, he just recently began selling, for the second time this year, hogs from his current group of pigs. Usually his barns are empty this time of year, “but because of disruptions and other things that have happened, they slowed the growth of pigs by manipulating the rations … and now we’re trying to catch back up because packing plants are running close to capacity.”

With cases of COVID-19 continuing to rise and uncertainty about how long disruptions caused by the pandemic may last, the future remains murky, he said.

“Things are so uncertain that we just don’t have any basis to make decisions on at this point in time,” said Zylstra, 69, who’s been farming since the early 1980s.

Big yields not enough

Farmers are facing near record or record production this year after what some experts say is one of the better years for planting in 30 years, and a big rebound from 2019 when wet conditions caused big delays in crops getting in the ground.

Projections are for Iowa to produce about 2.7 billion bushels of corn in 2020, and about 560 million bushels of soybeans, up from 2.58 billion bushels of corn and 500 million bushels of soybeans in 2019.

Nationally, corn production is projected to reach 15.2 billion bushels, up nearly 2 billion bushels from last year. Soybean production is expected to grow to 4.1 billion bushels nationally, up about a half billion bushels from the previous year. Futures for corn have lingered near $3.50 a bushel for corn, and about $8.70 a bushel for soybeans, about the same level as the past couple of years, but “still below the heyday of a decade ago,” said Chad Hart, an agricultural economist with Iowa State University.

Those production estimates could change depending on the weather.

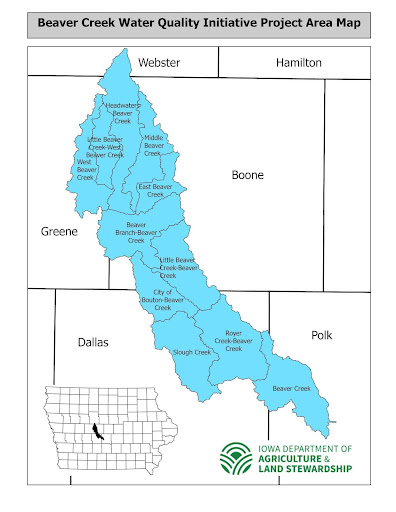

A recent map produced by the U.S. Drought Monitor showed abnormally dry conditions across much of western Iowa, with pockets of moderate drought in western Iowa.

The dry conditions come as corn begins pollination, and it could result in lower yields, Hart said.

“We’ve had a great start, but we may not have a great finish,” he said.

Even if big yields are harvested, they won’t, on their own, turn things around, said Grant Kimberley, who farms with his family in northeast Polk, southern Story and western Jasper counties.

“Even if we have a record crop this year, the best thing it does is help us get back to breaking even. It really doesn’t give an opportunity for a profitable year, unless prices go up a little and stay there a while,” Kimberley said.

Agricultural markets have been in a bear market since 2013-14, said Kimberley, who is also the director of market development for the Iowa Soybean Association.

Kimberley said U.S. farmers have been hit hard by the downturn, despite large crops in recent years, not only in the U.S. but overseas, too. At the same time, the U.S. dollar strengthened while foreign currencies weakened, he said.

“When you have large global production and a strengthening dollar, it makes U.S. exports more expensive, so it made us a little less competitive on the world market,” Kimberley said.

As foreign currencies, particularly in Brazil, continues to weaken, production there will continue to increase and further stress U.S. markets, he said.

Zylstra said farmers are looking at ways to become more efficient and spend less as available capital for investing back into their operations dwindles.

“I do a lot of my own repair work,” he said. “We find equipment that still has some usable life to it, and make some repairs to it and try to keep it going. You can invest a lot of money to have the latest technology and stuff, but yeah, we’re just trying to be careful with our expenditures.”

Hart said problems with liquidity have been developing for farmers for the past few years, and with crop prices dropping to the lowest levels in more than a decade, the problem is worsening.

“We’ve seen consolidation with ag input suppliers, we’ve seen not only a capital drain, but also a people drain within our rural communities, and you’ve seen government efforts to try to help,” Hart said.

He cited market facilitation payments and $50 billion allocated through the CARES Act to help stimulate rural communities suffering from the pandemic, but the challenges facing farmers are continuing.

“It has impacted farmers, it has impacted those ag input suppliers, like seed, equipment, chemicals and fertilizers, and that problem spreads … because a lot of our rural communities are still heavily agriculturally dependent,” Hart said.

A “big ask”

Kimberley said several factors need to align for the U.S. agriculture economy to improve.

One, he said, is better enforcement of the trade deal with China, which buys 60% of the world’s soybeans. China was also hit by the African swine fever at about the same time as the trade dispute erupted, resulting in as much as 40-50% of its hog herd being culled, pushing down their demand for grain, Kimberley said.

About 60% of U.S. soybeans are exported, with at least half of that going to China.

“If we were comfortable that the trade deal with China was going to be implemented as it’s written, and no other geopolitical issue gets in the way that would destabilize that deal, and if we knew the Renewable Fuels Standard was going to be implemented as we all thought and as Congress intended it to be, then our demand would pick up in a hurry,” Kimberley said. “Those are a pretty big ask, and it’s a little bit of a stretch to assume all those pieces are going to fall together.”

Photos by Michael Crumb. Top: Eighty-five percent of the state’s corn crop is rated in good to excellent condition after a nearly perfect start to the season, but challenges such as expanding drought, trade and fallout from the coronavirus could keep this year’s crop from reaching record levels, despite what some are calling the best planting season in decades. A cornfield south of Ames is dotted by wind turbines while storm clouds billow to the east. Bottom: Corn is tasseling in a field south of Ames as seen Tuesday night, but dry weather and expanding drought conditions could reduce this year’s yields, keeping producers from seeing near record or record production.