Seeing the future in construction

Digital catalogs and virtual reality allow builders, designers and owners to see what they have before it is constructed

KENT DARR Jun 17, 2016 | 11:00 am

4 min read time

988 wordsBusiness Record Insider, Real Estate and DevelopmentMatt Hillis and John Ryan were talking high-tech advancements in the construction and renovation of tall buildings at the same time they were folding a very low-tech-looking piece of cardboard. Looks, of course, can be deceiving.

What the two senior project managers for Ryan Companies US Inc. produced was something called Google Cardboard, and when you put it on your face the views that swirl behind the 45-millimeter lenses the contraption contained are of the future.

This future will be a three-story atrium with conference rooms hanging like flower boxes along the sidewalls and a 9,600-square-foot skylight overhead at Principal Financial Group Inc.’s headquarters in Des Moines.

Hillis and Ryan have just introduced a visitor to the use of virtual reality. It has emerged in the past two decades in the architecture and engineering fields, with enhancements delivered by the warehousing industry and video gaming.

Ryan is the general contractor for Principal’s $250 million renovation of its offices and grounds. A few blocks away, the company also is leading construction on the $156 million Krause Gateway Center.

Building information modeling and virtual design construction play a key role for architects, engineers, builders, fabricators, parts suppliers and pipefitters on both projects.

Mike Prefling, director of virtual design construction for Ryan, said the process helps owners make sure that their vision for a project is being carried out. Construction professionals scattered from France to South Dakota find out within minutes of a change of plans.

Smartphones and tablets are carried around a construction site, as opposed to paper plans. Ryan sets up workstations with big-screen monitors and small printers where superintendents at a job site can check the specs on the layout of ductwork, for example, or search for answers when they come across the unexpected, say a tower column hidden behind a wall on a renovation project.

Not an issue on new construction, but somewhat common on older buildings, such as Principal’s Corporate One, that might have undergone a couple of revisions over their life spans.

For Principal, nearly every element of the original construction and later revisions have been captured in photographs and drawings and detailed paperwork. All of the information has been put into digital files and combined with every element of the renovation. A single image of a piece of plumbing at Corporate One contains more than 12,000 hyperlinks to corresponding data that could represent the actual nuts and bolts of a product.

Building information modeling (BIM) involves compiling all of that information into a 3-D format. Virtual design construction takes that information and puts it to use. If BIM is the car of the contemporary construction site, virtual design construction is the driver, Prefling said.

“Beyond design, the construction BIM is nuts and bolts, fabrication-level detail,” he said. “We actually build twice. We build it virtually, we sequence it, we optimize it, we coordinate it, then we actually go build it. It’s not illustrations. It’s not cartoons. We actually go build it.”

The car and the driver have been slow to arrive at the gates of a construction site.

“The construction industry forever has been incredibly stagnant, as far as production and efficiency,” Prefling said. “A Department of Labor study looked at all nonfarm industries over 50 years, and construction was the only one that had declined in productivity. For 50 to 75 years, it had been stuck in kind of doing everything the same way. It was all based on processes from the 1960s and 1970s.”

Then architects and engineers began turning to their computers in the early 2000s. They pitched their T-squares and drafting boards and did their work in a three-dimensional digital format. It was interesting stuff, but several years passed before construction companies and their subcontractors embraced the change.

“The manufacturing industry would laugh at us and say, ‘We’ve been doing this for 25 years,’ ” Prefling said.

Prefling arrived at Ryan about 15 years ago as a civil engineer. Seven years ago he began dabbling in BIM and virtual design construction. Four years ago, leaders at the Minneapolis-based construction giant decided the company was going to make a commitment. Prefling was tapped to lead the effort.

“I started out as a one-man crew,” Prefling said. “I have been converting teams one at a time, one project manager at a time; now every team is asking for more.”

Prefling, who is based in Phoenix, said Ryan’s Greater Des Moines office has been quick to embrace BIM and virtual design construction. He attributes the conversion to an office staffed with young professionals who are open to change.

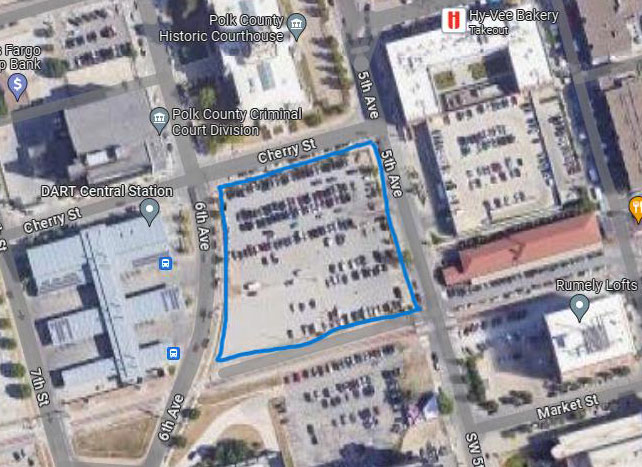

In late February, he made a one-day stop at Ryan’s construction office for the Krause Gateway Center. Crews were nearly finished excavating nearly 68 tons of dirt from the site, and Prefling was in town to dabble in the virtual world. Months of high-level design efforts by architects and engineers were wrapping up the form and function aspects of the project.

“Now we’re hiring contractors. Now we do care if that duct might hit that pipe. We’ll be in high-intensity mode for the next several months,” Prefling said.

Digital planning stations will be located on site. They function as sort of a construction community information center. If a design changes, it will show up on a computer monitor at the planning station, as well as on smartphones and iPads carried by vendors.

“A pipefitter can see the most recent plans,” Prefling said. “When new drawings come out, you go to your phone, and bam, there it is. It’s easy to get the information to workers in the field. It’s accurate, it’s controllable.”

After the Principal and Krause projects are completed, the digital information will stay behind and can be used as a resource for building management.

“It leaves behind more of a predictive operations scheme,” Prefling said. “That’s the big money. 70 percent of the cost of a building is operation and maintenance.”