Unprecedented times: A look at how small businesses have adapted to the coronavirus

EMILY BLOBAUM Apr 21, 2020 | 11:01 pm

6 min read time

1,540 wordsArts and Culture, Business Record Insider

The orders to close came in waves. March 17: all bars, restaurants, gyms, theaters and gaming facilities. March 22: salons, spas, barbershops, tattoo parlors, tanning facilities and pools. March 26: bookstores, clothing and shoe stores, home furnishing stores and cosmetic shops. April 6: malls, amusement parks, bowling alleys, libraries, zoos, campgrounds and playgrounds.

Small businesses, which rely heavily on foot traffic from local residents and visitors, are being hit particularly hard.

In a survey conducted by the Greater Des Moines Partnership with 600 respondents last month, 62% of Des Moines metro organizations said they’ve made operational changes in response to the pandemic. When asked about the biggest concerns surrounding COVID-19, 89% mentioned the impact on loacal and small businesses. Additionally, 13% of respondents said they were concerned that their business may not be able to sustain or recover from the effects of the pandemic. Twenty-four percent were anticipating needing up to $100,000 in financial assistance, with others needing more.

The federal government passed a $2.2 trillion aid package last month, allocating $367 billion in loans and grants for small businesses across the country. That will certainly help, but small business owners in Iowa have still had to make difficult decisions in an attempt to stay afloat.

These are the stories of how three Des Moines-area businesses have adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It was the right thing to do.” – Scott Bush, owner, Foundry Distilling Co.

Scott Bush, owner of Foundry Distilling Co., was on a family vacation in Florida when the COVID-19 pandemic really seemed to take over the country in mid-March.

His employees back in West Des Moines were texting him with updates, saying “things were getting weird.” Stores were closing left and right. Downtown streets were empty. Toilet paper and hand sanitizer were becoming hard to come by.

Let’s see what we can do about it, Bush told his team. He instructed Greg Biagi, who graduated with a degree in chemistry from Drake University, to get to work on a recipe for hand sanitizer.

A few days later, Bush and his team decided they would distribute tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of their 60% ABV (alcohol by volume), 120-proof hand sanitizer for free. They would distill between 600 and 700 gallons of the product per weekend, until there was no longer a need.

“We’re still a startup business so it’s been somewhat challenging, but we were willing to shoulder the cost of it just because we’re in such extraordinary times,” Bush said. “I think it was certainly the right thing to do.”

They put out a release on Facebook on March 19 that instructed community members to bring their own containers and to stop by the distillery in Valley Junction between the hours of 12 and 6 p.m on March 20.

Meanwhile, Bush booked a flight back to Des Moines the next day and immediately hailed a cab to the distillery.

He arrived to find hundreds of cars lining Railroad Avenue, waiting to fill up on hand sanitizer.

“I had always wanted to see that — just under different circumstances,” Bush said.

For more than six hours each day that weekend, Foundry employees and a small army of volunteers worked nonstop running back and forth between the parade of vehicles and the pop-up tent that housed 6-gallon pails of the sanitizer solution.

And every weekend since — albeit in a shorter time frame now, just one day per weekend for four hours — they’ve continued distributing to those in need.

“We call ourselves Des Moines’ distillery. We are part of the community, we built this to be a part of the community,” Bush said. “We want things to get back to normal as soon as possible and our hope is that people remember that we stepped up and someday when the world is not ending and they want to buy a bottle of vodka or whiskey, they’ll support the Foundry.”

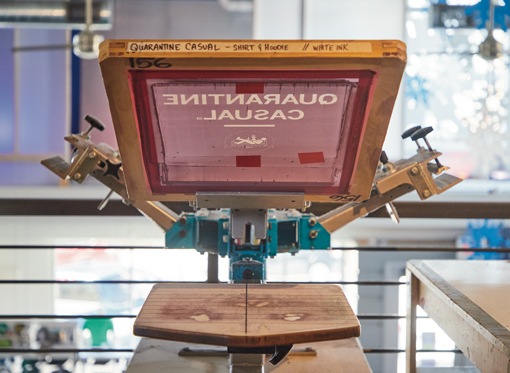

“Closing all retail locations [was] unprecedented.” – Mike Draper, owner, Raygun

On any given day, hundreds of people can walk through the doors of Raygun’s location in the East Village.

For the last six weeks, though, its 7,000-square-foot store has remained empty. Most of the lights are off. The radio is on, just to fill the near-silence. The handful of remaining employees are spread 6 feet apart as much as possible, adhering to social distancing guidelines. Trips across the store to ask a quick question have turned into sending a message through Slack.

“I opened the [physical] store originally because I like people,” owner Mike Draper said. “I liked the idea of opening a store and seeing people enjoy the stuff. And normally I sit overlooking the whole store. You get to hear people walk around and laugh at products. You work in an extremely public place. And to go from that kind of environment to where you’re now in the same store but it’s totally silent … your mindset is totally different.”

Raygun announced it was temporarily closing its doors for the first time since 2005 on March 17.

“It was a shock to go from never in 15 years have to lay off staff, then to go to laying off 70% of your staff in one day while you’re scrambling to close stores and put up signs,” Draper said.

From the start, Raygun’s M.O. was to be the store that brings the internet to life, as Draper put it. Walking around the store, it wouldn’t be uncommon to find a meme printed on a shirt about an event that happened the day before.

That being said, with more than 175,000 combined followers on its Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts, Raygun had an advantage heading into the pandemic: It had already built the machinery around having a strong internet presence.

It knows how to interact with its customer base by encouraging submissions for designs. It knows how to monopolize on what’s trending in the political and cultural spheres. The company has spent the last few years building up its website.

“We have the capacity to pivot and [continue to] sell stuff,” Draper said. “It sucks to close the stores, but we don’t have it nearly as bad as other people out there in other industries.”

Now the focus is on cranking as many designs as possible to move up the SEO rankings. Raygun’s product release schedule has gone from one design per day to four or five.

“We’re just trying to stay connected with our community.” – Ashton Israel, instructor, Power Life Yoga Barre Fitness

For Ashton Israel, an instructor at Power Life Yoga Barre Fitness, the answer to how to continue leading fitness classes during a pandemic lies in a pair of AirPods and an iPad tucked in the corner of a mirrored studio.

On April 9, Israel, who has taught at Power Life for two years, experienced leading a class of more than a dozen participants on YouTube Live for the first time.

For 45 minutes, she offered words of guidance and motivation as if the room were filled.

“Get those knees up. Come on, I see you. You’ve got this.”

“You are strong and you are capable. Keep pulsing.”

“You’re looking good, friends. Stay with it.”

Watching the class, you’d think she’d been leading online classes for years. But after the session ended, she let out a sigh of relief.

“I was so nervous,” she said after signing off. “I teach a lot, but I usually have a lot of people [in the room] and music to pace myself.”

Power Life, a boutique fitness studio with eight locations spread throughout the Des Moines and Kansas City metro areas, offers hundreds of yoga, power sculpt, HIIT and barre workouts to thousands of students every week.

That was all put on pause on March 16, when Adam Geneser, president and founder of Power Life, made the decision to close all studios.

“This is one of the most challenging decisions I ever had to make,” he began in a statement on Facebook. “Temporarily closing our doors is the best way to keep our community safe. … Please take care of your physical and mental health during this time, as well as that of others.”

His team felt obligated to maintain a sense of normalcy and offer a space for its community to disconnect for a while from a world saturated with coronavirus updates and work-from-home stressors.

Less than 24 hours later, Power Life began streaming its first free class on YouTube Live.

“We’re not trying to make money off of these classes. We just want to do what’s right for people, and offering it for free is the best way we can do that,” said Annika Peick, marketing director for Power Life.

As of April 10, Power Life had uploaded more than 80 live sessions to its YouTube channel. And while it’s too early to tell if they’ll continue offering online classes after the pandemic is over, they recognize that they’ve been able to reach a wider audience.

“We miss everyone so much and we know they miss us,” Israel said. “We’re just trying to stay connected with our community and try and keep people’s spirits up because this is a rough time.”